ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Problematizing Caste and Gender Discourse through Visual Metaphors in Indian Films

1 Assistant Professor, Department of Humanities, M.S. Ramaiah Institute of Technology, Bangalore, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Indian cinema,

both Bollywood and regional films have a tremendous impact on the minds of

the audience and invariably the society at large. Films respond to various

socio-cultural issues prevailing in a society. Apart from being just

entertainers, most films have a social message. For effective delivery of the

message, films do not rely only on dialogues. In fact, most of the things are

conveyed through visuals and signifiers such as sound, pictures, colours,

images, symbols, clothes, body language and so on, all pertaining to

non-verbal communication. Recent film makers use these cinematic techniques

for appropriation. In this context, this article explores the visual

signifiers in two regional films: the Tamil film Karnan (2021) and the

Malayalam film The

Great Indian Kitchen (2021). This research looks

at how the visual metaphors and signifiers in both the films foreground the

discourses on caste and gender. The

study makes us realize the significance of such cinematography in departing

the true spirit/essence of the films. |

|||

|

Received 20 March 2022 Accepted 20 April 2022 Published 06 May 2022 Corresponding Author Dr.

Premila Swamy D, dpremilaswami@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i1.2022.65 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Regional Films, Visuals, Metaphor, Signifiers |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Cinema has been a source of influence and appeal to the Indian populace since its beginnings. Many scholars have pointed the widespread popularity of films in shaping ideas, constructing images and in proliferating cultural values and ethos. Butalia (1984) claims that commercial films are influential means of communication. Indian films, both the mainstream Hindi cinema and the regional ones are active representatives of Indian realities. With its varied themes, characterization and cinematic techniques, today Indian cinema has received global recognition. No doubt, the visual medium in popular culture has revolutionized the way we perceive life around. Cinema unearths forgotten histories and becomes a platform to portray truth and hidden mysteries. Recent Hindi films like English Vinglish (2012), Margarita with a straw (2014), Lipstick Under My Burqua (2016), Gully Boy (2019) narrated pressing concerns of the society and opened up vistas for new perspectives. Cinema is also a mode of articulation, resistance, and platform for social change. With the discourses laid by postmodern and postcolonial thinkers there is an awakening consciousness of subordination based on caste, class and gender and rewriting the historiographies of the silenced voices. Both literature and visual media are dynamic in proliferating the necessary change and awakening our consciousness. Contemporary progressive film makers like R. Balki in Hindi, Nagaraj Manjule in Marathi, Vetri Maraan in Tamil to name a few are breaking stereotypes through cinematic narrative by raising pertinent questions related to marginalization. Today, literary writers and film makers are equally using different modes of representation to explore the socio-political-cultural concerns and engage in forming a collective consciousness against the established dictums that subjugate the ‘other’ in the name of caste/gender. The visual media through cinematic experience becomes a representative metaphor to speak for the oppressed minorities who have been silenced or misrepresented in the mainstream narrative. Oppression, deprivation, neglect, marginalization, and humiliation at various cross sections in the lives of the oppressed class are well captured through the cinematic lens. By critiquing caste, gender, class and other forms of oppression, cinema itself acts as powerful medium of resistance to hegemonic supremacy. Cinema, therefore, is a powerful agent of the society Chakravarty (1993), Griswold (2012), Lindner et al. (2015), Mulvey (1988).

Cinema has the ability to both construct and deconstruct cultural tendencies. In the process of its narration, it engages the viewers to understand deep rooted structures and help in perceiving things with a new approach. Within its thematic discourse, films are loaded with multiple meanings. Visual metaphors in this context play a significant role in bringing out the layers of meaning that the narrative unfolds. A close reading of filmic narrative tells us that every single ray of light, sound, colour, gesture, or object is there for some reason and has something to convey. Recent films choose to subvert and deconstruct old norms, ideologies, and tendencies. It questions ideologies and subjectivities and allows for newer ways of interpretating films. For the said purpose, film makers use visual metaphors such as symbols, images, and other representatives as a major ingredient in delivering the theme, essence, and true spirit of the narrative.

This article examines two regional films, Karnan (2021) and The Great Indian Kitchen (2021) and explores the significance of visual metaphors as a narrative technique. In the process of exploration, the article examines the usage of images, metaphors, visual signifiers used by the film maker Selva Raj in Karnan to re-represent and problematize caste politics on screen. Further, it goes ahead to examine the various visual elements in Jeo Baby’s The Great Indian Kitchen to emphasize the nature of gender binaries and varied constructs based on gender. The paper argues that using symbols and metaphoric representations, the film under study gives insights on the nature of social construct within the realm of caste and gender.

2. POST OCCUPANCY EVALUATION (POE)

2.1. THE LANGUAGE OF METAPHORS AND VISUAL METAPHORS

Metaphor in simple sense refers to a figurative expression widely used in literary art such as poetic imagination. Metaphoric expression refers to description of a person or object by referring to something that possesses similar characteristics. Lakoff and Johnson (1980) state that most people consider metaphor as a device of the poetic imagination and a rhetorical flourish rather than ordinary language. Johnson (1987) emphasizes that “Metaphorical projection is one fundamental means by which we project structure, make new connections, and remould our experience”. Similarly, Ricoeur (1991) asserts that metaphors increase our perception of reality by dismantling our sense of reality, and that reality undergoes phases of metamorphosis through metaphors. Since Aristotle, the role and significance of metaphors in creative processes is much discussed. Metaphors are not just something to do with language; they are also sources of thought and action. They involve all natural dimensions of our sense experience such as colour, shape, texture, sound Lakoff and Johnson (1980). These metaphors in turn allow us to read texts in multiple ways. The origins of verbal and visual metaphors are similar according to Rothenberg (2008). The concept of “visual metaphor” was first coined in scientific vocabulary by Aldrich (1968) but has been known and used in many fields. Rothenberg (1980) points the role of visual metaphors during creative processes in visual arts such as painting, sculpture, and architecture. If metaphors are related to words, phrases, sentences, and dialogues, the visual metaphor is related to images, scenes, colours, and anything related to visuals. Allen (2016) stated that the concept of visual metaphor is an extension, or a specialization, of a metaphorical thought into the pictorial semiotic system. According to Allen, the difference between metaphor and visual metaphor is in the object. This means, if metaphor focuses on the objects such as words, utterances, dialogues, and written or verbal things, then the visual metaphor focuses on the visual object such as newspaper cartoon, animation, advertisement, and film.

As this article’s focus is on films, I will direct my attention in examining the role of visual metaphors in films. Film makers use abundant visual metaphors to capture audience’s interest and curiosity as it is said that human mind can be reached faster by visuals. A visual metaphor is a creative way of telling the narrative using images, analogy, sounds, lighting, and colours; largely used by film makers as a part of cinematography. It acts as a powerful tool to connect with the audience and make a realistic approach. For example, The Harry Potter films are a treasure house of visuals. It brings to us a sense of perception and kindles our imaginative faculty, making us excited. These visuals are used to combine images, emotions, and expressions to represent various themes and situations. Contemporary cinematographers abstain from direct analogy and use narratives, historical events, and memories as metaphors. The film gets embedded with multi-layered, sophisticated meanings by constantly enabling mental shifts between the verbal and the visual metaphors. Metaphors thus helps us to construct meanings through its creative space. The significance of representational space or discovery is never absolute; on the contrary, it is always a matter of transformation and interpretation Foucault (1986). Metaphors become tools of identity and films use them in order to negotiate through similar or contrasting metaphors. Many scholars have examined the role of metaphors in films. For example, Comanducci, states that metaphors in films aid in understanding and signification and films can express themselves metaphorically (2010). Barsam and Monahan (2015) define that missen-scène, sound, narration, picture, and sequence aid in meaning making process. Forceville and Renckens (2013) analysed how light, and darkness are used to represent good/evil binaries in films. Further, Forceville and Paling (2018) examined visual metaphors portrayed in short animation films.

Studies have pointed out the dominance of visual images over writings and how they contribute to learning and perception Kress and Van Leeuwen (2006), Van Leeuwen and Jewitt (2001). As viewers, we don’t just listen to the dialogues, but we perceive more through visual metaphors such as images. Kumar and Pandey (2017) in their study state that symbols and nonverbal messages in cinema enables larger understanding of reality. In this context, the metaphorical meanings provide larger scope for viewers to uncover the context of the story moving beyond abstract meaning Lakoff and Johnson (1980). Indian film makers have no doubt made effective use of visual metaphors to deliver its theme and have larger impact on audience. Films like Ashoka (2001) which depicts the life of Indian Emperor of the same name is loaded with metaphors. In the film, the sword, fire, snake, peacock, lotus, mud bath offers metaphoric meanings to its narrative. Also, films such as Three Idiots (2009), Raavan (2010), Bahubali 2 (2017) provide wide range of visuals, well embedded into its plot and structure. Carroll (1994) states that film makers use visual metaphors in order to provoke viewers into thought processes which enables viewers to understand the image and correlate it with an intuitive meaning. Through visuals, viewers are engaged in meaning making process, making cinema, a text for understanding and exploration of subjects. In the light of these discussions, the present study explores two regional films: Karnan (2021) and The Great Indian Kitchen (2021). The objectives of this study are as follows:

1) To explore the usage of visual metaphors in the select films.

2) To identify the role of visual metaphors in problematizing caste/gender discourse.

2.2. EXPLORING THE ROLE OF VISUAL METAPHORS IN CINEMA

2.2.1. KARNAN AS A VISUAL TEXT OF CASTE POLITICS

Indian cinema has presented before us the caste reality in

India and the ways caste creeps in the everyday lives of common man in terms of

untouchability, honour killing in inter-caste marriage, caste conflicts and

power nexus between the dominant and lower caste. Tamil cinema has also

captured our attention in its portrayal of Dalit subjectivities. Contemporary

Tamil film makers like Pa. Ranjith Gopi Nainar and Mari Selvaraj have created

an unprecedented impact on the visual narrative in their representation of

subaltern caste politics. The oppressed people are no longer depicted as

submissive meek characters but having a strong assertive voice against

power/dominant structures. The ‘new narratives’ not just tell the saga of Dalit

life, rather it aims for an alternative narrative that deconstructs/decentres

dominant ideologies. Contemporary Dalit film makers use innovative techniques

in visuals, sound, music, and cinematography to rewrite the

stereotyped/misrepresented histories of the Dalits. Using suitable visuals,

they contest casteist monopoly and raise concerns for anti-caste aesthetics.

Tamil Film makers like Pa. Ranjith, Mari Selvaraj and

others use body images, dress code and blue frames to represent Ambedkarian

ideology on screen. Tamil films like Kabaali

(2016) and Kaala (2018) have at least

one screen dedicated to the blue colour, visually signifying Ambedkarian philosophy of egalitarian enlightenment and empowerment (Benson Rajan

and Shreya Venkatraman 2017). Body language and the dress codes have metaphoric

meanings suggestive of the emerging assertive voice of the subaltern classes.

Clothing too becomes an important visual signifier while representing

case/class. Usually, the bourgeois class gets represented in clean white

clothes while the Dalits are depicted wearing untidy shabby dark clothes Benson

and Venkatraman (2017), Gopalkrishnan (2019).

In Karnan, director Mari Selvaraj dwells deep into caste discrimination and exploitation, weaving into its narrative the historic Kodiyankulam violence of 1995 in Tamil Nadu and the Mahabharata myth. However, the film revolves around the conflict between two villages, Podiyankulam inhabited by subaltern caste and the adjacent village Melur with a dominant class. Podiyankulam is 1.5 km away from the main road and does not have a bus stop. The inhabitants need to use either Melur’s bus stop or use trucks or vans to commute to other places. The conflict escalates when the bus doesn’t stop for a pregnant lady nor for eleven villagers who wanted to get down. Repeated petitions to authorities seeking a bus stop for Pondiyankulam goes in vain. The elderly village populace suffer subjugation in silence but not the protagonist, Karnan, with the film’s titular name. Karnan fights the battle against oppression for his community, at the cost of murdering the exploitative IPS officer, SP Kannibaram and resultant imprisonment for 10 years. The village gets a bus stop, roads, schools, and other facilities. Karnan returns from prison and the community dances with joy. The narrative is a community’s fight against oppression, dominance and breaking free from silent subjugation, suffered through ages. To substantiate this ethos, the film accommodates in its narrative varied forms of images and metaphors, altogether making it a visual text for exploration. The director adopts various visual techniques and methods to articulate the Dalit perspective.

Karnan is a saga that is subversive which conveniently uses the Mahabharata myth to deliver its anti-caste message. It also comes to us as a tale that retells Mahabharata from a subaltern perspective. In Mahabharata, the character, Karna undergoes taunts and insults as he is thought to belong to family of charioteers and therefore ‘inferior’ in caste. Although Draupadi longs to marry him, caste disparity comes as a barrier. The film Karnan uses this myth and subverts the tale by bringing the lead character Karnan as focus and representative of his class. The film opens with reinforcement of the love tangle between Draupadi and Karnan. Unlike the mythic character, Karnan has a strong voice to fight against caste discrimination. Thematically the epic and the film are narratives of fight against injustice and victory over truth. Karnan is a quest for justice and equality. Karnan speaks for his caste and community. The Mahabharata tale is subverted and retold to deliver the present caste politics and related oppression. All other characters in the film too possess names of mythic characters as in the epic. The director Mari Selvaraj has given voice and identity to these characters and Draupadi too gains more agency in the narrative.

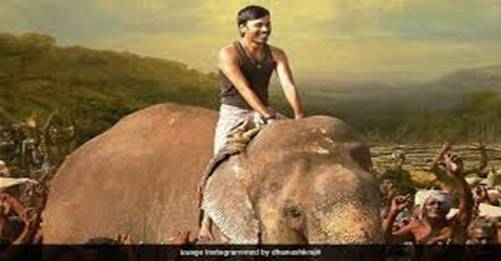

What is striking to observe is the liberal use of images from nature. The background and scenes are set in a rural backdrop surrounded with natural setting. This immediately allows the director to make generous use of birds and animals for their role and implied meaning. Within its narrative, the film brings to its world a wide range of metaphors such as the village sword, elephant, horse, donkey, kite, and the rural deity named Kaatu Peichi. All of them are symbolic and very suggestive of the theme. These images and visuals signify human emotions and also bring emotional and aesthetic impact. The film has recurrent references to the predatory bird kite, both in dialogues and in visuals. In fact, the very first scene is the cry of an old woman whose chicks have been carried away by the predatory bird. The disgusted woman pleads to release her chicks but when her persuasion doesn’t bear fruit, she curses the kite saying someone would soon break its wings. This is paralleled by Karnan who becomes victorious in the village contest and lifts up the village sword. Seated on an elephant, Karnan and his team march towards the village symbolizing victory and strength. Howerever, Karnan has to fight many more social oppressions for his community. The portrayal of a donkey represents the working class, oppression and a beast meant to carry the burden. The camera frequents to the tired legs of the donkey metaphorically suggesting slavery and bondage to social structures that curtail freedom and mobility. Karnan is disturbed with the sight of the donkey and wants to let it free which he does towards the end metaphorically suggesting his community’s freedom from slavery. Another interesting observation is the camera’s deliberate focus on human legs suggesting the bondage suffered by minorities in a casteist society. In fact, the opening scene shows a young girl discarded on the road to die in the middle of an epileptic fit with no vehicles to take mercy and stop. This is Karnan’s sister who frequently appears with a mask representing the local diety, Kaatu Peichi, who becomes a guiding force for the local population. The frequent focus on human legs is a deliberate strategy to suggest the need for freedom and upward mobility. When Karnan releases the legs of the donkey, things turn different. Amidst all violence, torture and death, the village gets a bus stop and other facilities representing growth. Towards the end, Karnan rides a horse which is again suggestive of majesty, strength, and freedom. The image of donkey and then the subsequent ride on a horse towards the end suggests transition from slavery to freedom. The village celebrates at its victory over its fight against basic rights. Although Karnan takes a major role in unifying the village, the tale is that of a community’s fight for justice. Unlike other films, the hero is not romanticized or glorified, nor he becomes a saviour for the community. Karnan is just a member of the communication, representing a young generation who dare to fight for justice. The birth of the child at the end suggests a new awakening, a new generation whose voices are visible and heard.

Animals and nature take a key position in Mari Selvaraj’s world. In Pariyerum Perumal (2018), the dog, Karrupi, sets the tone and the mood. In Karnan, it is the horse and the donkey. Karnan rides on the horse at the end suggesting victory, power, and strength. The whole film talks about liberation. Death too acts as a metaphor and is used as a constant reminder of that which brings rebirth, life, and continuity. The headless bust, the death of Karnan’s sister in the opening scenes and death of the village oldman, the grandfather, Yeama and the birth of the baby resonate tragic journey, sacrifices, and rebirths to liberate the community.

A few captures from the film shown below serve the purpose

of illustration.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Shows the

Village Sword That Karnan Wins, The Headless Bust of Humanoid, And the Local

Deity Source: Author

from the Tamil film Karnan (2021) |

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Shows Karnan, Returning Victorious After Winning a

Local Contest Source: Author from the Tamil film Karnan (2021) |

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Shows Karnan’s Discomfort at The Tied-Up Legs Of A

Donkey Source: Author from the Tamil film Karnan (2021) |

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 Represents

Karnan in His Majestic Ride on A Horse to Fight the War Against Oppression Source: Author

from the Tamil film Karnan (2021) |

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Shows the

Collective Voice of The Community in Its Fight for Basic Rights Source: Author

from the Tamil film Karnan (2021) |

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Represents Kaatu Peichi the Local Deity Who Is a

Guiding Force Source: Author

from the Tamil film Karnan (2021) |

Songs and music too are vital in conveying the necessary essence. The song “Uttradinga” meaning “Don’t give up” addressing all mothers, fathers, grandfathers, brothers, sisters, and the entire community is a call for the community to rise against all atrocities and fight for the rights. The pain of the torture meted to the villagers towards the end is paralled with the labour pain of a pregnant mother. Amidst the violence, torture, and pain, Yeaman (the grandfather) immolates setting fire to himself to stop the relentless police brutality. At this juncture, the baby is born; Kannabiran (the police officer who represents power) is beheaded; and the headless portrait on the village wall gets Yaeman's face as a tribute. The birth of baby and its cry is suggestive of emergence of speech/assertion over silence/dominance.

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Shows Ending of

The Film with The Wall Painting Carrying the Face of Yeama Source: Author

from the Tamil film Karnan (2021) |

Within its

narrative, Karnan carries anti-caste

sentiment fused with anger, frustrations against atrocities, oppressions, and a

determination to win through resentment, resistance, and protest to get the

basic human rights. Relying more on visuals, images, symbols, body

language than on dialogues, the film has layered meanings and therefore makes a

suitable visual reading on caste politics. On the surface level, Karnan

might seem like a familiar tale of struggle between the oppressed and

oppressor, but Mari Selvaraj's detailing makes the film feel both unique and

universal at the same time. Using birds and animals, Mari Selvaraj recreates

the Mahabharata and builds a wider canvas to represent power nexus between oppressor

and the oppressed.

2.2.2. CAPTURING ‘GENDERING’ THROUGH VISUALS

Gender discrimination and women’s issues under patriarchy

has been one of the focus areas of Indian cinema. Both mainstream Hindi cinema

and regional films have dealt with questions of identity and gender

subjectivity. Jeo Baby’s

Malayalam film, The Great Indian Kitchen

released through the OTT platform in January 2021, is a clarion call against

misogyny and a plea for women to fight injustice within family spaces. Taking

the recent Supreme Court verdict providing women, the accessibility to enter

Sabrimala temple in Kerala as its backdrop, the film probes into the very

dynamics of gender constructs that are naturalized and regulated within

domestic spaces. The film revolves on the marital life of a young girl and her

journey in ‘adapting and adjusting’ in a conventional family, rooted with

patriarchal ideals. The kitchen becomes a central space for the narrative to

unfold and in the process, the director shows us how men and women perform

their gender determined roles where men occupy public spaces, engage in leisure

activities, relish food and women are seen completely engaged in processing and

preparing food (Mathew 2021). The female lead character leaves

aside her passion of being a dance teacher, only to cook, clean and take care

of domestic responsibilities that is hardly noticed and appreciated by the male

counterparts. The film is a critique on heterosexual marriage, family structure in patriarchy which

‘normalizes’ gendered performances where women are expected to perform within

the spaces of the kitchen, only to make the family happy. It is interesting to

note that none of the characters are named, thus signifying universal notion of

men/women gender performances. Although there is complete absence of physical or domestic violence,

abuse, the suffocating experience of the protagonist is shown through silence

and visuals. Unable to withstand, toward the end of the movie, the woman leaves

these oppressed spaces to gain autonomy, self-control and to cherish her

dreams. The workings of the camera and the visuals play a significant role to

unearth questions related to gender constructs.

Thematically,

The Great Indian Kitchen exposes

power dichotomy between gender binaries which paves way for gendered

performances in gendered family spaces. For the said purpose, visuals act as

powerful tool in conveying the messages. The camera focusses minutely on every

detail in the kitchen and on the elaborate ways of food preparation, right from

cutting, grinding, chopping, frying and all related activities. And this is not

shown one time but is repeated. The camera also takes our direction towards

photographs hung on wall. This is accompanied by sounds of clinking of pans,

sizzling of dishes or the whistling of pressure cook signifying the repetitive

works performed by women. Again, the repetitive focus of the camera on kitchen

spaces, women working, and the photographs hung on the wall is an illustration

how these gendered ideas and performances have been repeatedly performed

through generations. The deliberate attempt of the film maker to focus our eyes

on the photographs---mostly of married heterosexual couples indicates

how certain ideologies are naturalized and passed on to generations. Kitchen

becomes a spatial metaphor of confinement, femininity, and unpaid labour. Photographs too become an important

metaphorical agent. The

visuals arouse pertinent questions on the spectator’s mind in the ways men and

perform their roles based on their gender identity. The kitchen in the movie

occupies larger screen space. Every single aspect in a common Indian kitchen

gets captured along with the repetitive tasks that women are confined to. With

lesser dialogues and more visuals, the director shows the various pitfalls in

our society and leave spaces for us to contemplate.

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Visuals on

Kitchen Drudgery and Women’s Unsaid Labour Source: Author

from the Malayalam film The Great Indian Kitchen (2021) |

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 Photographs

Representing Marriage and Heterosexual Life Source: Author

from the Malayalam film The Great Indian Kitchen (2021) |

Using brilliant visual representations, the film questions the existing stereotypes operating in the society and shows how family and marriage contribute to uphold patriarchal norms to gain control over the other. Without showing any violence on film and with minimal dialogues, the film has drawn our attention to gendered spaces and activities that silently creeps in family structure, limiting women’s expression and freewill.

3. OBSERVATIONS AND CONCLUSION

Films have visual impact on the audience mind. Much is seen and perceived through our senses. Visuals on screen be it a bird, animal, colour, or a photograph, they have larger things to connote. Emerging film makers have successfully used this. Films like Karnan and The Great Indian Kitchen stand testimony for this. It is rare in Indian cinema that kitchen has occupied a central space to speak for women’s unseen labour at home. Karnan deals with caste politics and is a perfect visual text that enumerates many questions related to caste and is a successful tale of resistance and liberation from oppression. Karnan as a counter narrative to hegemonic caste structures, maps the transition of Dalit’s passivity/submissiveness into resentment, resentment into resistance, and resistance into assertion for dignity and basic human rights. The film, The Great Indian Kitchen itself is metaphorical. Much is ‘shown’ rather being told. Using the cinematic space and varied techniques, the film negotiates for gender equality within private spaces. However, it can be noted that not every film is loaded with visual images. For example, Jai Bhim (2021) released this November, engages with caste and related exploitation but with minimal visuals as compared to Karnan. Even then, the film did a commendable job in delivering its message. Needless to say, visual metaphors and other signifiers does help film makers, but it need not be the only mandate tool for effectiveness. However, in the two regional films discussed here, the polemics of caste and gender are unearthed with apt visuals.

REFERENCES

Allen, E. (2016). The role of visual metaphors in brand personality construction - a semiotic interpretation. Master dissertation. Finland: Aalto University School of Business.

Baby, J. (2021). The Great Indian Kitchen. Ernakulam, Kerala, India.

Barsam. R, & Monahan, D. (2015). Looking at movies: An introduction to film (5th ed.). New York, W. W. Norton & Company.

Benson, R. and Venkatraman, S. (2017). Fabric-Rendered Identity : A Study of Dalit Representation in Pa. Ranjith's Attakathi, Madras and Kabaali, Artha-Journal of Social Sciences, 16(3), 18-19.

Butalia, U. (1984). Women in Indian Cinema. Feminist Review (17), 108-110.

Carroll, N. (1994). Visual Metaphor. In : Hintikka, J. (eds) Aspects of Metaphor. Synthese Library, 238.

Chakravarty, S. S. (1993). National Identity in Indian Popular Cinema, 1947-1987(Texas Film and Media Studies Series). University of Texas Press.

Comanducci, C. (2010). Metaphor and ideology in film. MPhil dissertation. United Kingdom, The University of Birmingham.

Elmo, A. (2022). The role of visual metaphors in brand personality construction - a semiotic interpretation.

Forceville, C. & Paling, S. (2018). The metaphorical representation of depression in short, wordless animation films. Visual Communication, 1-21.

Forceville, C. J., & Renckens, T. (2013). The 'good is light' and 'bad is dark' metaphor in feature films. Metaphor and the Social World, 3(2), 160-179.

Foucault, M. (1986). Of Other Spaces, Diacritics, 16(1), 22-27.

Gopalkrishnan, S. (2019). Marginalised in the New Wave Tamil Film : Subaltern Aspirations in three films by Bala, Kumararaja and Mysskin. Rupkatha Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 11(2), 1- 9.

Griswold, W. (2012). Cultures and Societies in a Changing World, Sage Publications.

Johnson, M. (1987). The Body in the Mind : the Body Basis Meaning and Reason, Chicago University Press.

Kress, G. & Van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading Images : The Grammar of Visual Design, London, Routledge.

Kumar, H. and Pandey, G.J. (2017). Deconstruction of symbols of Reality in Hindi Cinema : A Study on Calender Girls and Haider. Media Watch 8 (3).

Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By, University of Chicago Press.

Lindner, A. M. Lindquist, M. and Arnold, J. (2015). Million Dollar Maybe? The Effect of Female Presence in Movies on Box-Office Returns. Sociological Inquiry 85, 407-428.

Mathew, S. (2021). Analysing body, autonomy and gendered spaces in the great Indian kitchen. Feminism in India.

Mulvey, L. (1988). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. In Feminism and Film Theory. Ed. Constance Penley.

Rothenberg, A. (1980). Visual Art, Homospatial Thinking in the Creative Process, Leonardo, 13(1), 17-27.

Rothenberg, A. (2008). Rembrandt's Creation of the Pictorial Metaphor of Self, Metaphor and Symbol, 23(2), 108-122.

Selvaraj, M. (2021). Karnan, V Creations, Chennai, India.

Valdes, M.J. (1991). A Ricoeur Reader in Reflection and Imagination, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Van Leeuwen, T. & Jewitt, C. (2001). Handbook of Visual Analysis. London : Sage Publications.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2022. All Rights Reserved.