ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

An approach to the architectonical method through the

analysis of the Dutch Embassy in Berlin by Koolhaas & OMA

1 Teacher

at IDarte, Basque School of Art and Higher School of Design, Spain

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This article ventures into the investigation about

method in architecture, that is, about the way in which we think and create

architecture. In order to achieve such an objective, the article simply

re-thinks a specific architecture that already exists, the Dutch Embassy in

Berlin. In this way, architectonical object and work are considered the

susceptible elements that provide the material knowledge that unravels the

manner and the methodology by which they were conceived. A sensitive and intuitive itinerary through the

graphic documents published about the embassy allows us to access a

continuous narrative dissertation that deconstructs the conceptual issues

that have constituted the building. Thus, this paper developed an

object-based method, as opposed to traditional and orthodox text-based

research. This does not preclude the inclusion of innumerable references

related to the conceptual issues that we can find in this architectonical

analysis (Ungers, Vidler, Somol, etc., see citations and bibliography). In this way, the paper differentiates itself from

the scientific-historical research. Having it as a support, the paper opens a

new way for future research which can be specifically focused on the

architectonical project's methodology. At times, this research development can be

disconcerting. This is because architectonical method, our way of thinking

and creating, is never analytically structured. Neither can a text that tries

to unravel the creative method be strictly linear. For this reason, this text

is an essay that tries to introduce us to the deepest motivations of a

project, most of the time intertwined in the form of spiral paths, cyclical

paths that unite and contradict each other at the same time. Therein lies the uniqueness of this study. A second article [1] complements this analysis of the Embassy with an

itinerary that, in this case, extends its route to other buildings by

Koolhaas. This second paper also uses other comparisons with other historical

references, for example, Venturi. Both articles find

in Koolhaas' method strategies based on a paradoxical conceptual identity, a

diagrammatic coherence that coexists with the greatest semantic

inconsistency. The impossible concordance between form, meaning and image.

The scepticism towards the impossible unity, which, at the same time, pursues

a challenging unitary iconic condensation. |

|||

|

Received 22 March 2023 Accepted 15 June 2023 Published 28 June 2023 Corresponding Author Eneko Besa, enekobesa@idarte.eus, enebed@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i1.2023.372 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License. With the license

CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download, reuse,

re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work must

be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Design Method,

Methodology, Dutch Embassy, Berlin, Rem Koolhaas, OMA |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. A narrative analysis

This paper focuses specifically on the analysis of one singular work by Koolhaas, the Dutch Embassy in Berlin. Thus, beyond Koolhaas’ controversial writings and polemical statements aiming at the generic, this analysis resolves categorically to focus on the specificity of one particular architectonic work to end up with the methodological conclusions that come out from it. Figure 1, Figure 2

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 The Dutch Embassy in

Berlin Source http://duitsland.nlambassade.org/organization/de-ambassade/het-ambassadegebouw |

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 The Dutch Embassy

and its Context Source http://duitsland.nlambassade.org/organization/de-ambassade/het-ambassadegebouw |

This choice of the Dutch Embassy is not just based on

Koolhaas’ architectonic beginnings in Berlin,[2] Patteeuw

(2003) Figure 3 nor only on the fact

that this is one of the less analysed of his recent buildings. Rather, the Embassy,

behind its apparent anti-Koolhaasian compact severity, offers such

dissociations and dysfunctions of its structural-significant condition, that

its choice approaches one of the most genuine Koolhaasian manifestations. Figure 4

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 The Berlin Wall in

S, M, L, XL. Images used by Koolhaas to show his thoughts about the Wall. Source KOOLHAAS,

Rem. MAU, Bruce. OMA. S, M, L, XL. The Monacelli Press, New York 1995. |

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 The Dutch Embassy, Open

Courtyard Source http://duitsland.nlambassade.org/organization/de-ambassade/het-ambassadegebouw

|

In fact, parallel to the subversive contradictions of Koolhaas’ work, the Embassy emerges from a paradoxical dilemma between the requirements of his client (the Netherlands) and its venue (Berlin).

“the client demanded a solitary building, integrating requirements of conventional civil service security with Dutch openness. Traditional (former West Berlin) city planning guidelines demanded the new building to complete the city block in 19th Century fashion.” EL CROQUIS. (1987-1998), 414

The conceptual idea of the building comes out of the

conflictive synthesis between the obedience towards urban-planning rules and

the self-assertion which constitutes the modern autonomous volume. Figure 5

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Aerial Picture of the Embassy and its Context Source Drawing

by the Author |

“We can

further explore a combination of obedience (fulfilling the block’s perimeter)

and disobedience (building a solitary cube).” EL CROQUIS. (1987-1998), 414

This synthesis is directly translated into a conceptual

drawing or sketch that comes to describe an intervention based on an autonomous

building, a cube, supported by a podium that defines and completes the

perimeter of the block where it is located. Figure 6

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Conceptual Scheme Source OMA |

“Our proposal (…), a freestanding cube on a –block completing- podium.” EL CROQUIS. (1987-1998), 414

Therefore, the whole intervention is based on the dialectical relationship between two complementary/contradictory elements. On one hand, the podium plus the irregular volume which both belong to the same mass that fulfils the block. On the other hand, the free-standing volume or cube that stands on top of the podium. This is the dialectic between supporting and supported, which in turn extends into a formal/informal dialectic, since the regularity of the cube of the offices is contrasted by the irregularity of the volumes on which it stands. Figure 7

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 The Dutch Embassy. Open Courtyard Source Author |

The informality of the “supportive” element is strengthened by its construction in aluminium perforated sheet, which gives it the necessary neutrality to become the background of the main building. On the contrary, the façade of the “cube”, main volume, is a curtain wall façade which distinguishes it from its metallic background. While this curtain wall façade prolongs the neutral austerity of the metallic irregular shape, it establishes a complementary dialectic and mutual reference between both elements. This analogy is reflected in the sketch, where the front cube suggests a kind of continuity due to the dotted perforations that represent the aluminium sheet behind, even though there is no correspondence with the materials that eventually built the Embassy. Figure 6

Indeed, the main block acquires different connotations

beyond the robustness of its volume. Defined as an autonomous block, it can be

understood in continuity with its own basement. Distinguished from the rest of

the building, at the same time it prolongs the height of the block from which

it is segregated. Being an independent

entity, the surface of its roof is represented in analogy to the volume that

fulfils the block. However, the main ambiguity of this cube is its own form and

constitution since it has the same shape of the void of the courtyards of the

block where it is located despite being a solid volume. Figure 8

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 A: Void/Solid. B:

First Void/Solid Inversion C:

Second Void/Solid Inversion Source Author

|

Thus, this synthesis between obedience/disobedience leads Koolhaas to reverse the solid/void dialectic, since the voids of the cubic yards of the block are transformed into a built volume, also cubic. Conversely, the irregular volume which embraces the patios in the traditional block is turned into the void of the ‘irregular’ courtyard that surrounds the main volume of the building. In other words, Koolhaas turns around the traditional scheme, transforming void into solid and mass into space. Shifting hollowness into density, and its inverse, construction into a gap between two buildings.

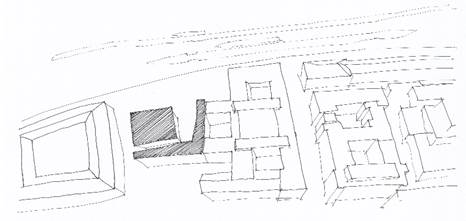

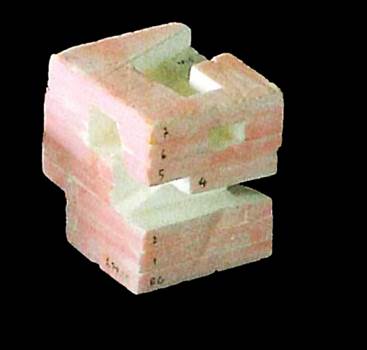

Figure 9

|

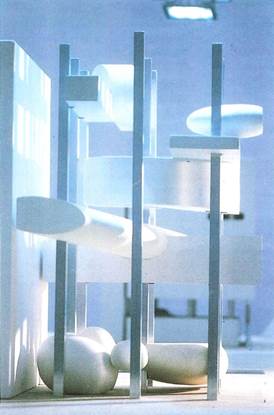

Figure 9 Working Model Source OMA |

This solid/void dialectic that constitutes the exterior

volume is also extended into its interior, as the public outward space extends

inward along a corridor throughout the volume of the cube that guides the

visitor to the top floor of the building. Figure 9 This drilling finds an

ambivalent representation in the models that Koolhaas presents, since it is

alternatively defined either as emptiness (dug hole) or as fullness (massive

volumes within an interior empty space). This once again leads us to understand

the conceptual void/solid inversion as one of the main themes that underlies

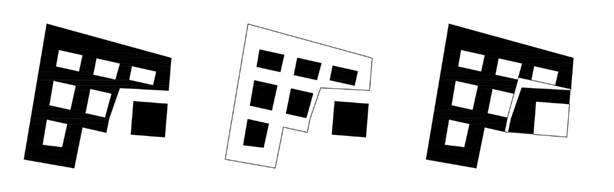

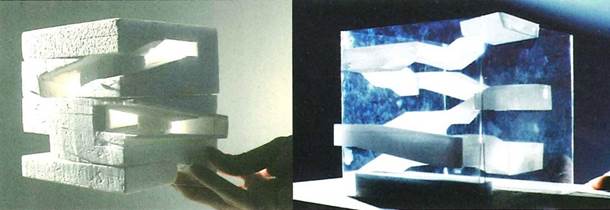

the building. Figure 10

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 The Same Promenade Represented Alternatively as

a Void or as a Solid Source OMA |

This kind of representation has a clear precedent in the

models of the Library of Paris, where the hollow elements, empty forms, have

become the most representative elements of the building. Figure 11 As such, the elements

created by the emptiness are the ones that acquire the most iconographic

significance. In short, this is a mechanism that models the shape by its

negative piercing instead of by the traditional positive constructive

displacement. There are also other manifestations of this procedure in

Koolhaas’ work: Agadir Convention Centre, Utopolis Project in Almere, A Casa da

Música in Porto and its predecessor Y2K House, Ascot Residence, Torre

Bicenteneraio in Mexico City, etc. Figure 12

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 Paris Library Model Source OMA |

There are also many historical references of this solid/void inverted representation, some of which can even be found in relation with Koolhaas’ academic life, particularly in Cornell University where Koolhaas met Rowe and Ungers[3] Koolhaas (2006). Nevertheless, these two references of drawing and modeling, Rowe/Ungers, are beyond a mere technique of representation as they personify the two sides of the same figure/ground gestaltic inversion.

Figure 12

|

Figure 12 Agadir Convention Centre. Sections Source

KOOLHAAS, Rem. MAU, Bruce. OMA. S, M, L, XL. The Monacelli Press, New York

1995 |

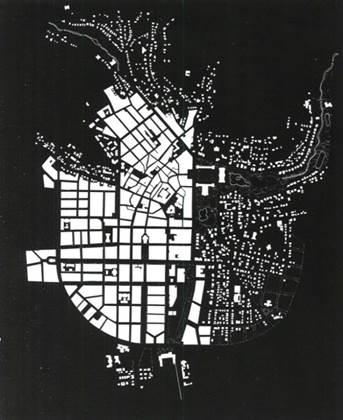

Indeed, the Rowe/Ungers opposition represents two complementary understandings of the public space/private mass dialectic in traditional/modern cities. On one side, Rowe, and his preference for the typology of the traditional city, where –mainly regular- hollows were vacated from the irregular urban morphological tissue. On the other side, Ungers and his archipelagos, which belong to the reversed modern typology, in which the regular forms of buildings stand upon the generic extension of Cartesian space. Figure 13 and Figure 14

“Rowe posed the problem characteristically as a juxtaposition. If ‘regular’ freestanding buildings tended to create ill-defined, amorphous exterior space, he concluded that conversely, if one wished to make ‘regular’ well-defined spaces, then irregular buildings would be required.”[4] Caragonne (1994), 349.

Figure 13

|

Figure 13 Image on the Cover of Collage City Source ROWE, Collin. KOETTER, Fred. Collage City |

Figure 14

|

Figure 14 A Comparative Between Traditional/Modern Cities in Collage City Source ROWE,

Collin. KOETTER, Fred. Collage City |

Then it is obvious how this solid/void representation refers to the two opposite regular/irregular typologies that are interwoven in the Embassy.[5] For these architects, the representation of the negative black/white shape not only refers to the solid/void dialectic but also to modern/traditional conceptions of the city, as well as to the differences between public/private space, and to interior/exterior polarity in relation to the limit of built shape.

Precisely, this limit between interior/exterior is

responsible for the strong determinative character that is defined in

black/white representations by Rowe and Ungers. In the case of Koolhaas

nevertheless, this limit loses its consistency, and it is no longer a mere

exclusive juxtaposition thanks to the promenade that inserts itself from the

exterior, breaking down the boundaries of the original volumes. As the limit of

the building has been destroyed, ‘burst’ by a promenade as if it were a

dermatological parasite that gets under the skin, it leaves visible marks of

the scars through its way. Figure 15.

Figure 15

|

Figure 15 The Promenade’s

Scars on the Façade Source http://duitsland.nlambassade.org/organization/de-ambassade/het-ambassadegebouw |

However, in this case, such scars are not always prominent because they are shown alternatively as introducing indentations into the surface of the building or as volumes that exceed the limit of the façade, i.e., as voids into the solid or solids over the solid. Thus, Koolhaas breaks the strong solid/void duality by which Rowe’s sketches were defined.

And so, once the consistency of the interior/exterior

duality is weakened, Koolhaas reverses that relationship with a new turn of the

screw. In this case, by a positive volume that inserts itself into its negative

inverse void, which is the box that cantilevers from the main building into the

courtyard of the Embassy. This volume hosts a key element of the program, the

ambassador’s reception room, which is stripped of its intimacy and pushed out

to be defiantly exposed to the gazes from the exterior. Figure 6 and Figure 16.

Figure 16

|

Figure 16 The Ambassador’s

Reception Room Source Http://Duitsland.Nlambassade.Org/Organization/De-Ambassade/Het-Ambassadegebouw

|

Thus, similarly to the way in which the void was introduced into the solid, this solid is now the element which is inserted into the void. But this cantilevered volume is not only an independent element but rather it can have its origins in the promenade itself. As if the promenade, drilling the building, had pushed its entrails out, forcing the most intimate room to leave the centre that would correspond to a traditional humanist interpretation.

“The centre

relies on what is supposed to be built around it. Alternatively, the centre is

always ‘foreign’. It is something brought in from outside, by definition

without justification, to found something new and different to what was there

before.” Coyne

(2011), 24

“The centre depends on the periphery” Coyne (2011), 33

Beyond these speculations that interpret this volume expelled by the promenade, beyond whether this was the case or not, it is obvious that both, the ‘spat out’ volume and the terrifying drill of the promenade, respond to the same will: the interest to uncover all the intimacy and interiority that architecture has represented so far.

On the contrary, other interpretations in some publications about OMA’s work refer to the austere exterior of the Embassy and comprehend the interior as a surprising space which is hidden from the exterior of the building. In contrast, one could also understand the Embassy’s interior directly exposed through the drilling operations that have been made upon it. Thus, the interior would be stripped out rather than secretly kept. Indeed, although the building shows the restrained appearance of its façade, it also makes evident the scarring operations of the promenade over it. It is the paradox by which an apparent severity attenuates its expression of a terrible denuding operation[6] Koolhaas (2006).

Beyond the conceptual and dialectic coherence of all the

operations performed over the Platonic solid, their result and their

connotation provide the building with a radical and subversive tinge. And so,

the coherence of all the dialectics described so far, interior/exterior, obedience/disobedience, solid/void, and so on,

coexists with the subversion that is the result of the application of that

conceptual coherence to its most extreme consequences, since, as we have seen,

the analysis of solid/void dialectic has led us to comprehend the subversive

interior/exterior relationship in this building.

This is the conflictive relationship between interior and exterior of buildings that Koolhaas explicitly refers to in his Conversations with Students Koolhaas (1996). With his words in those conversations, Koolhaas points out certain operating forces that work in the socio-cultural contexts which come to transcend traditional procedures that have generated architectonic form so far:

“The first observation is that, in a building beyond a certain size, the scale becomes so enormous and the distance between center and perimeter, or core and skin, becomes so vast that the exterior can no longer hope to make any precise disclosure about the interior. In other words, the humanist relationship between exterior and interior, based upon an expectation that the exterior will make certain disclosures and revelations about the interior, is broken. The two become completely autonomous, separate projects, to be pursued independently, with no apparent connection.” Koolhaas (1996), 15

In some new commercial architectonic manifestations Koolhaas perceives such vastness of their scale and size that the centre of the building reaches a dissociation from its limit, forcing us to reconsider the correlative relationship that the interior and exterior had in traditional humanistic discipline. Since the exterior is no longer able to articulate and respond to its volumetric immensity, the skin of the building can be totally independent from its inner content and can even receive other assignable content. Thus, according to our time, the skin can be a matter of plastic surgery to model the external image of the body releasing it from its most intimate entity. This operation can even be extended to question the identity of a person, and even its gender, an extreme that Pedro Almodóvar shows in his film The Skin I Live In.[7]

The case of the Embassy does not present properly a skin, neither is the building large enough to correspond to this theory by Koolhaas which comes from the proclamations concerning the vast Bigness[8] Koolhaas (1995). However, the intentions behind his theories have found their own course in the building of the Embassy, not because the interior is denied by a skin that hides it –or detaches from it-, but rather because the exterior invades it. Indeed, the promenade that is introduced from the exterior towards the interior of the building implies a traumatic operation that invalidates any attempt to recover the intrinsic consistency of the pure volume of classical architecture.

To the extent which it could be said that this is a

building without interiority, since, it has been wholly formalized by the

contingencies and parameters that are introduced from the exterior, as the

entire building has been primarily designed outside-inwards. Even the promenade

itself and other singular elements in this building are so externally modelled

from the outside references to the point that it is literally skewered by the

context. Figure 17, Figure 18.

Figure 17

|

Figure 17 The Context of the

Embassy Modelling the Promenade Source OMA |

Figure 18

|

Figure 18 Views Along the Promenade Source http://duitsland.nlambassade.org/organization/de-ambassade/het-ambassadegebouw |

“The

trajectory exploits the relationship with the context, river Spree, Television

Tower (‘Fernsehturm’), park and wall of embassy residences; part of it is a

‘diagonal void’ through the building that allow one to see the TV tower from

the park.” EL CROQUIS. (1987-1998), 415

Due to these outside influences which have operated upon it, the Embassy becomes permeable to the exterior view, suggesting typical Dutch transparency by which dwellers show the intimacy of their homes through their ‘naked’ windows. It is not only a matter of exposition of intimacy but again a matter of inversion, since the building shows a permutation of privacy that also has its origins in Berlin itself.[9]

At this point the reader should have a comparative look at

Figure 5 and Figure 6, also Figure 19, to observe that the

entire complex has not been completed yet. Another project, also designed by

Koolhaas, (the headquarters of Anthroposophical Movement) continues the

irregular volume of the embassy completing the entire urban block. That project

has not been built yet. Consequently, one of the private patios of the block

remains open to the street that is behind the Embassy, Stralauer Straße. Meanwhile, the public space of the embassy

communicates though a large irregular hole with this open courtyard, allowing

crossed views from both sides. Figure 19

Figure 19

|

Figure 19 Built and Unbuilt in

the Block Source Author |

In fact, walking down the Stralauer Straße at the back of the Embassy, we find ourselves looking at the courtyard of the Embassy through a hole, thinking that we are curiously meddling in a private area. Then we suddenly realise that we are not intruding into an intimacy from an exterior, but rather that we are looking through a hole in a party wall, from a private courtyard which is open because the block is not concluded yet. Figure 20.

Figure 20

|

Figure 20 View of the Open Courtyard from Stralauer Straße Source Author |

Indeed, what we are observing through the hole is the public area of the building (public courtyard of the embassy). Meanwhile, the windows that are opened widely in the façade in front of us relate to the private part of the complex, as they are the windows of the private houses of the embassy that should look on to a private courtyard not yet closed. Because, these are the homes of some of the staff and the guard of the embassy, housed in the interstitial building that Koolhaas uses to adjust the embassy to the block as the background of the main building. These homes open their windows to the courtyard of the embassy and to the adjoining patio, which is right now open to the street, as the block has not been completed yet as is characteristic of Berlin. In the end, we feel like voyeurs, caught in the act, intrusive yet exposed. We have the sensation of meddling in an intimacy, while being naked due to the carnal nudity of the characteristic party walls of one of the heartbreaking gaps that still remains in the centre of Berlin.

Another one of the most disquieting episodes showing this ambiguous condition of intimacy is the moment in which the floor of the promenade is transformed into glass. Figure 21 Our solid floor disappears just when the promenade is aligned parallel to a Nazi building, and we are accompanied by the repetitive gloomy rhythm of its windows. Thus, our support sinks beneath our feet precisely when we find ourselves in front of one of the most uncertain milestones of our recent past.

What is more, just in this precise moment when we lose our sense of safety and we wonder if the floor will withstand our presence, just when we discover that our own ‘butt’ is exposed to the gaze of anyone in the street, we find ourselves located right next to the working area of the embassy from which only a glass wall separates us. Thus, without intending to, we are intruding into a private area, observing it from a slightly elevated place, and therefore, from a superior position. Again, it is the same inverted voyeurism through which we find ourselves interfering with someone else’s privacy while our own intimacy is more exposed than ever.

Figure 21

|

Figure 21 The Promenade, when its

Floor Becomes Glass Source http://duitsland.nlambassade.org/organization/de-ambassade/het-ambassadegebouw |

However, these connotations about the inversion of the intimacy that can be perceived in the building, are hidden under its austere image. Insurgent episodes like these are concealed under a coat of apparent neutrality, which makes their subversive allusions even more unusual, given the building’s sober character and restrained expression.

In relation to this subversive transparent neutrality,

materials assume a key role, since they are played out to show indiscriminately

their constructive semantic ambiguity. Specifically, glass and aluminium

perforated sheet show this double, contained yet subversive, condition. Since

both are going to appear solid and consistent from certain perspectives, while

permeable and indiscreet from other points of view and different lighting

conditions. Figure 22, Figure 23

This fact illustrates how the character of the building fulfils its institutional requirements and responds to its necessary diplomatic distance, whereas a closer analysis leads to the discovery of disturbances of conventional order and subversions of its institutional program. This also shows how this restrained image does not reflect the subversive content that it connotes.

Thus, this building shows a complete dissociation between its image and its content. But also, the Embassy’s subversive connotation coexists with its most rigorous conceptual order, since, as this analysis has shown so far, this building’s most extreme nudity coincides with –and comes out of- the conceptual scheme where all its paradoxical dialectics come together: interior/exterior, void/solid, formal/informal, continuous/discontinuous, public/private, obedience/disobedience, regular/irregular, modern/traditional, etc.

Figure 22

|

Figure 22 Massiveness, Transparency and Reflections

Making the Public/Private Inversion Stronger Source Author

|

Figure 23

|

Figure 23 Aluminium Shed Source Author |

This means that beyond the double dissociation image/meaning, Koolhaas also dissociates conceptual form from its subversive connotation, which somehow illustrates that this building reaches a triple dissociation conceptual-form/meaning/image. Surprisingly, this is the similar disjunction of constitutive elements of architecture which we can find in the words of Koolhaas about the context of the Embassy, specifically in his analysis of the Berlin Wall:

“It was

clearly about communication, semantic maybe, but its meaning changed almost

daily, sometimes by the hour. It was affected more by events and decisions

thousands for miles away than by its physical manifestation. Its significance

as a “wall” –as an object- was marginal; its impact was utterly independent of

its appearance. (…) I would never

again believe in form as the primary vessel of meaning.” Koolhaas (1995), 227

Nevertheless, even though Koolhaas gets us used to his provocative statements which aim at the illicit subversion of the traditional values of the architectonic discipline and their subsequent dissociation, at the same time and in this same project of the embassy, we can find Koolhaas’ unusual interest in a unique conceptual coherence. Such willingness becomes explicit in Koolhaas’ words describing the design of the air conditioning that runs along the promenade which is “slightly over pressurized”. El Croquis (2006), 415 This is designed so that the leading element of the building “works as a main air duct from which fresh air percolates to the offices to be drawn off via the double (plenum) façade”. (Ibid.) Figure 24 As OMA’s description of the project continues:

Figure 24

|

Figure 24 Air Conditioning

Schemes Source OMA |

“This ventilation concept is part of a strategy to integrate more functions into one element. This integration strategy is also used with the structural concept.” (Ibid.)

This interest in one synthetic idea that leads the whole project could be reminiscent of a designing method by which architecture finds its own legitimacy and support in the conceptual identity through which it is thought. Synthesized in a sketch, in a formal scheme, one conceptual diagrammatic idea condenses all the dialectics that constitute the project (interior/exterior, void/solid, formal/informal, continuous/discontinuous…), in the same way that this diagrammatic idea is responsible for supporting all the decisions taken during the whole design process.

2. Some historical references

The conclusion of the previous analysis of the Embassy shows a widely used method in the architecture teaching realm, since it provides the student with the necessary argumentative skill to account for all decisions of the project. And it provides the skill to synthesize in one inclusive scheme all the problems that converge on the exercise which he/she faces. However, beyond the scope of teaching, and also within it, the seeking of an idea that supports the architecture through its intrinsic concept may have its origins in the moment in which the legacy of the ancients began to lose its undisputed authority.

“in opposing the “Ancients”, one group held to the idea that a good work of art is a creation in accordance with an idea in the artist’s mind.” Drew (1979), 101

As the former ancients were questioned by the emergence of the autonomous illustrated subject, architecture could not find support in their legacy anymore. It became necessary to find its legitimacy in a concept, to be based on an idea.[10] Madec (1997), 62

“The first of the three steps in making a design consists in putting down on paper a rapid sketch which presents, in preliminary form, the essence of the idea in the mind of the designer. (…) called a pensiero, or thought (…).

The third and last step consisted in bringing these studies into a final synthesis, a final design, that was a visual culmination of the idea in his mind.” Drew (1979), 114-115

The aim was to find such consistency during the design process that the decisions, and the method itself, were directly identified with the conceptual idea of the architecture that was being projected:

”An idea, so to speak, is the cornerstone around which to build the design”

“(…) in the development of the design process, Hoesli had stressed to his students the importance of gaining an overarching “idea” that would clearly illustrate and express an architectural response to the requirements of program, site, and structure. The emergence of that architectural idea as a basis for the development or “working out” of a student’s architectural exercise lay at a critical juncture in the design process –somewhere on the cusp between the pre-drawing, analytical phase and the first early sketches.”

“The idea of an architectural design is that spirit which is felt throughout the design, the spiritual part of the building… It is the thought in the designer’s mind that guides him in every decision and ultimately results in the continuity of the whole design…”[11] Caragonne (1994), 264

These previous quotes refer to the Texas Rangers era at The Texas School of Architecture, which has already been quoted and is also directly related with Rowe. They show that architecture was seeking so yearningly its identity as an idea that the design was even identified with the thought which constituted it. Thus, this unachievable quasi-spiritual synthesis made architecture reach a congruent ‘whole’ that tried to unify old existing metaphysical dissociations between matter and spirit, between form and idea.

Beyond the attractive suggestions of some of these statements, their aim could be even seen as idealist, a naive synthesis of the elements that were split up by the analytical philosophy. That is because the identity that an idea provides may not be enough to unite the elements that Kant had already differentiated trying to preserve the universality of the judgement of taste. Indeed, the ideal concept in which the Texas Rangers found a spiritual unity had already been dissociated by Kant, who tried to safeguard the sense of taste distinguishing it from the conceptual order of the object.[12]

“(…) perfection gains nothing by beauty or beauty by perfection; but, when we compare the representation by which an object is given to us with the Object (as regards what it ought to be) by means of a concept, we cannot avoid considering along with it the sensation in the subject. And thus when both states of mind are in harmony our whole faculty of representative power gains.” Kant (1914)

Extending his analytical method, Kant even distinguished the conceptual order of the object from its utilitarian application. And along the lines of the preservation of the common sense of beauty, Kant also differentiated aesthetic objectivity from the expression of the sublime. [13]

“We have now only to resolve the faculty of taste into its elements in order to unite them at last in the Idea of a common sense.” Kant (1914)

Within our disciplinary field, and through a theory that came to question the authority of Greek Orders Kaufmann (1952),[14] Perrault also made a distinction between positive beauty (objective) and arbitrary beauty, orientating himself with this differentiation towards the objectivity of the first one Herrmann (1973).[15] That is because his differentiation, and Kantian analytic differentiation as well, by their simple enumeration of different parts of the aesthetic judgement, had already started leaning towards one of them. This is due to the fact that these analytical enumerations actually belong to the objectivity of one of their elements, i.e., their whole procedure is in fact part of the rational thinking implied in the conceptual positive beauty that they try to separate.

Thus, Kant was opening a path for Hegel, since the difficulty implied in the transcendentality of the common sense of beauty eventually made architecture set its foundations within the pure conceptuality of what was thought. Therefore, due to architecture’s unreachable aesthetic objectivity, it was required to base its legitimacy on the ideal of an abstract concept.

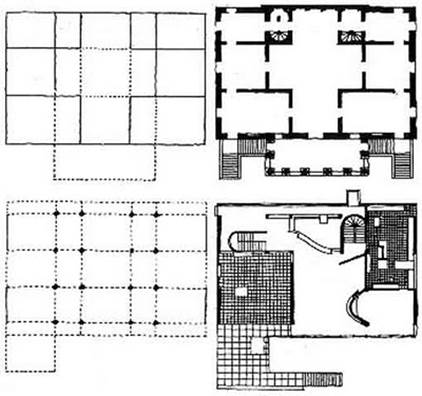

“This is the

definitive moment, (…): the moment when things take a form. The architectural

is basically, then, something that surpasses the concrete and necessarily

belongs to the domain of the abstract.” Mansilla (2000), 98

Figure 25

|

Figure 25 Rowe’s Comparative between Palladio and Le Corbusier Source ROWE, Colin. The

Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays. The Massachusetts Institute

of Technology, Cambridge y London, 1976 |

Therefore, if architecture can be reduced to an abstract concept beyond its specific embodiments, it can also be conceived through a conceptual scheme where all different dialectics find place, as is clear in the conceptual scheme of the Embassy.[16] This is the idealism that was later extended to the structuralist tradition, in which architecture could eventually be reduced to a schematic structural diagram. The structural schemes by Wittkower[17] summarizing Palladian architecture could be placed within this context. And also, this is the same concept that led Rowe to compare Le Corbusier and Palladio beyond their formal and specific particularities. [18] Figure 25

Thus, in the aforementioned traditions,[19]

i.e., in the idealism and in the scientific-structuralism traditions, the well

balanced scale of the elements of Kantian judgment ended up leaning towards one

of those elements. And so, architecture was oriented towards its

structural-spatial foundation, due to its plastic and formal condition. This led architecture to be

conceived through its conceptual/ideal schematic representation rather than

through its literary or metaphorical connotations.

“For as the pictorial effect was devalued and the intellectual aspect of architecture, the spatial/structural idea, was lifted into prominence, there is in the work of this period a direct elemental quality; a conscious effort to employ only the most limited means in order to convey its ideas.” Caragonne (1994), 258-259

“Semantically,

the architectural idea was nearly always expressed metaphorically, but in a

visual rather than a literary sense.” Caragonne (1994), 264

Thus, emphasizing the objective condition of the conceptual idea, the support that architecture found in the consistency of its formal scheme shifted the interest from its meaning to its structure, opening the door to future dissociations between the architectonic conceptual frame and its semantic connotation.

In the following quote by Luis

Moreno Mansilla, the reader can notice the preference of the ideas over

the meaning and personal connotation of architecture: “In the process of formation, then,

each thing takes its own path: the structure acquires a specific character, the

floor plan begins to fray around an object, the materials come into focus on

the basis of memory. Or anything else. It is not important. What is important

is the movement between things and ideas. A constant to-and-fro between the

ideas that are related to forms and the forms that suggest ideas.” Mansilla

(2000), 98.

“It is not important”. It does not matter. The content does not matter, neither architecture’s connotative allusions. What matters is the consistency that architecture reaches in its correlative identification between form and its conceptual support. This position comes from the moment when modernity opted for its conceptual framework over the conflictive ambiguity that is innate in the question of meaning.

3. Conclusion

The end of the previous epigraph shows the same fracture, the same forgetfulness of the semantic condition of architecture that we find in the Embassy in its most extreme consequences. Where the solid/void abstract coherence, carried to its most logical consequences, has led to the inversion between interior/exterior, and therefore to the nudity of this building’s intimacy. This means that the same idea which was the basis of the building has been carried out to the extreme of dissolving it. Thus, it leads this architecture to the dissociation between its supportive frame and its signification, between concept and its meaning.

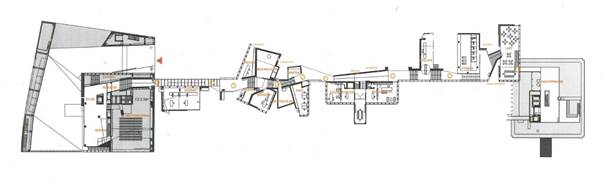

To the extent that the promenade, the script which connects all the different sequences,[20] is at the same time culpable for the subversion of traditional architectural relationships. The promenade, being responsible for the plot, is also the element which un-structures architecture’s own principles and rips out the inner unity of the original pure prism. Figure 26 This operation makes the Renaissance’s indissoluble interconnection between formal structure and its meaning disappear. In essence, it breaks the connection between denotative structure and its connotation. As the Embassy has already shown, being designed from its maximum conceptual coherence, its formal identity leads it to the representation of its own semantic disintegration. Therefore, this building’s identity coexists with the loss of its nuclear integrity, while its consistency connotes the most inconsistent meaning.

Figure 26

|

Figure 26 The Promenade

Unfolded Source OMA |

Thus, Koolhaas reaches this difficult synthesis by which architecture seeks its legitimacy through the risky game of its own slippery instability. In essence, he finds the identity through the sublime exacerbation of the most terrifying beauty. Figure 27

“Koolhaas takes his own radicality and cold search for the “sublime” quite far in an eschewal of intellectual comfort and a celebration of the “terrifying beauty” of the twentieth Century.” Chaslin (1999), 15

In fact, Koolhaas found a similar terrifying expression in the context of the Embassy. Unlike other locations,[21] his sympathetic comments about this context prove Koolhaas’ interest in a place that witnessed one of the most terrible manifestations of 20th century horror: the Second World War and its extension into the Cold War, particularly manifested in the Berlin Wall.

“The wall suggested that architecture’s beauty was directly proportional to its horror.” Koolhaas (1995), 226

Figure 27

|

Figure 27 Interior of the

Public Courtyard Source Author |

Thus, it could be concluded that Koolhaas translates his understanding of the context of the Embassy through an immediate reflection of its environment’s connotation, particularly of his ideas about the Berlin Wall. In fact, this relationship between the Embassy and its context would not be a misguided conclusion. Because, as proven, the embassy building has lost its interiority from its own basis since it has been conceived from the outside, from external operations that have been performed upon its conceptual volume and model.

In this way, being designed from the exterior, the Embassy building shows an uncritical assumption of the connotations of its closed context. Indeed, it is clear that some described episodes are derived from the nods that the building makes to the context: the glass floor of the promenade, the holes, some views, etc. Nevertheless, it seems that these individual episodes are also forcing some connotative expression out of the naked conceptual abstraction by which this building has been conceived. Figure 28 This somehow demonstrates the path of this analysis. Because, beyond the subversive character of some elements, the most naked expression of this building and its starkest connotation come from the extreme process of the rigorous conceptual operations of its design.

Figure 28

|

Figure 28 View Through the

Public Courtyard Source http://duitsland.nlambassade.org/organization/de-ambassade/het-ambassadegebouw |

This is a fact that, in turn, could also have its origins in the context, since this is an environment which has, again and again, witnessed how the most inhuman destruction can originate from the most supreme ideals and rational values. Thus, in the same way that the greatest absurdities of the 20th century had their origin in the maximum consistent rationality, this building’s inconsistent meaning could also have its source in modern systematic operations that have led its design process to its conceptual nudity.

This leads us to wonder about the voluntary intentions that lie behind this building’s semantic connotation.[22] Is this building’s subversive meaning simply triggered by some perverted elements which are related to the context and also come from Koolhaas’ insurgent intentions? Or rather, does the whole building involuntarily show its radical inconsistency from its own conceptual conception? A conception which, in turn, is apparently based on a rigorously consistent procedure.

In fact, these provocative episodes coexist within the conceptual-structural unity that Koolhaas refers to when he uses the order provided by the air conditioning system to describe the building. This reveals a contradiction with his own statements about inconsistency and makes us wonder how such conceptual stability can be found in a work by an architect who champions such subversive values. How can Koolhaas describe the consistent framework of the building while he aims at its illicit subversion? How can a maximum coherence be found in a work by an architect who defends the worst inconsistency of his own work?

Moreover, all these facts raise the question: would this building be nothing without its conceptual consistency and is that the reason why Koolhaas needs this indispensable sustainability? Does it represent an unavoidable ‘constructive’ framework within the pretended ‘deconstructive’ meaning? Or rather, is the coherent consistency of this project an involuntary humanist heritage, the last moral fortress that has yet to be destroyed? [23]

In essence, all these conjectures come to question the indiscriminate assumption of diagrammatic conceptual design as a projecting method, since this methodology may be more involuntary than we might think as it has its sources in the modernity that we still belong to.

Hence, this is the reason why this paper insists on the fact that these methodological conceptual operations have led architecture to the oblivion of its semantic condition. The same semantic oblivion which forced postmodernism to call for an iconographical recovery.

But postmodernism was rarely able to overcome its ‘decorated shed’, which was a mere iconographic ‘layer’, overlapping the modern structure that it was also detached from. A future paper will focus on the iconographic condensation of some projects by Koolhaas which represent an attempt to overcome these irreconcilable dissociations.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Aureli, P. V. (2001). The Possibility of an

Absolute Architecture. The MIT Press.

Ballantyne, A. (2007). Deleuze & Guattari for Architects. Collection Thinkers for Architects. Routledge.

Besa, E. (2015). Arquitecto, obra y método. Análisis comparado de diferentes estrategias metodológicas singulares de la creación arquitectónica contemporánea. Tesis Doctoral, ETSAM UPM. OAI.

Besa, E. (2017). Architect, Work and Method. IDA : Advanced Doctoral Research in Architecture. The Index and the Conclusion of the PhD Thesis of the Author are Published in English, 1157-1179.

Besa, E. (2021). Arquitecto, obra y método : Kazuyo Sejima, Frank O. Gehry, Álvaro Siza, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Zumthor. Diseño Editorial. Published as a Book in Spanish.

Besa, E. (2022). #eindakoa (what we have done) : A Pedagogical Method of Interior Design Studio Method. Journal of Design Studio, 4 (2), 179-202. https://doi.org/10.46474/jds.1207503.

Besa, E. (2022). Dynamics-Aktion- Pedagogical Dynamics Proposal, Useful for Design Studio Teaching and Beyond. ShodhKosh : Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, 3(1), 349-377.

https://doi.org/10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i1.2022.118

Caragonne, A. (1994). The Texas Rangers. Notes from an Architectural Underground. The MIT Press.

Chaslin, F. (1999). “The Gay Disenchantment” Published in OMA Rem Koolhaas. Living. Vivre. Leben. Arc en reve. Centre d’Architecture/ Birkhauser Verlag.

Chaslin, F. (2004). The Dutch Embassy in Berlin by OMA / Rem Koolhaas. NAi Publishers, Rotterdam.

Cohen, S. (1998). “Physical Context/Cultural Context : Including it All.” Published in : HAYS, K. Michael (ed.). (1998). Oppositions. Princeton Architectural Press, 65-104.

Collins, P. (1965). Changing Ideals in Modern Architecture (1750-1950). Faber & Faber. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1970.10790388.

Cortés, J. A.

et al. (2006). AMOMA REM KOOLHAAS (I) Delirio y más. EL CROQUIS.

Nº 131/132.

Cortés, J.A. et al. (2007). AMOMA REM KOOLHAAS (II) Teoría y práctica. EL CROQUIS. Nº 134/135.

Coyne, R. (2011). Derrida for Architects. Collection Thinkers for Architects. Routledge.

Dovey, K. & Dickson, S. (2002). Architecture and Freedom ? Programmatic Innovation in the Work of Koolhaas/OMA. Journal of Architectural Education, 5-13.

Drew, D. (1979). The Beaux-Arts Tradition in French Architecture. Princeton University Press.

EL CROQUIS. (1987-1998). OMA / Rem Koolhaas. 1987-1998. EL CROQUIS. Nº 53+ 79.

Eisenman, P. (1999). Diagram Diaries. Universe. Rizzoli International Publications.

Gargiani, R. (2008). Rem Koolhaas. OMA. EPFL Press.

Heidingsfelder, M. & Tesch, M. (2009). REM KOOLHAAS, más que un arquitecto. Arquia/ Documental 8.

Herrmann, W. (1973). The Theory of Claude Perrault. A. Zwemmer LTD.

Kant, I. (1914). Critique of Judgement, Translated with Introduction and Notes by J.H. Bernard (2nd ed. revised).

Kaufmann, E. (1952). Three Revolutionary Architects : Boullée, Ledoux and Lequeu. The American Philosophical Society.

Koolhaas, R. & Mau, B. (1995). S, M, L, XL. The Monacelli Press.

Koolhaas, R. & McGetrick, B. (2004). Content. TASCHEN GmbH.

Koolhaas, R. & Yoshida, N. (2000) OMA@work.a+u Architecture and Urbanism : May 2000 Special Issue. The Japan Architect Co.

Koolhaas, R. (1994). Delirious New York. A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. The Monacelli Press.

Koolhaas, R. (1995). “Bigness of the

Problem of the Large”. Originally Published in : Koolhaas, R. & Bruce, M.

(1995). S, M, L, XL The Monacelli Press.

Koolhaas, R. (1996). Conversations with Students. Architecture at Rice. Rice University School of Architecture, Houston. Princeton Architectural Press.

Koolhaas, R. (2006). Post-Occupancy. DOMUS d’autore.

Koolhaas, R. et al. (1997). O.M.A.

Programa d’acció. Quaderns monografies. Collegi D’architectes de Catalunya.

Madec, P. (1997). Boullée (Cristina Lachat Leal

trans.) AKAL ediciones. (originali published in 1984).

Mansilla, L.M. (2000). “Aprender es dibujarse en el mundo”. BOHIGAS, Oriol (Ed) La formación

del arquitecto. Simposio internacional. Quaderns d’arquitectura i urbanisme y

Colegi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya.

Moneo, R. (2004). Inquietud Teórica y Estrategia Proyectual en la obra de ocho

arquitectos contemporáneos. ACTAR.

Muñoz, A. (2008). El Proyecto de Arquitectura. Concepto, Proceso y Representación. Editorial Reverté.

Olbrist, H.U. [Architecture Biennale] (2010). OMA Office for Metropolitan Architecture (NOW Interviews) [Video]. Youtube.

Pasajes. (1998). OMA Revista : PASAJES.

Arquitectura y crítica. Nº 59.

Patteeuw, V. (2003). Considering Rem Koolhaas and the Office for Metropolitan Architecture. What is OMA. NAi Publisher.

Rowe, C. (1976). The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Rowe, C. (1978). KOETTER, Fred. Collage City. The MIT Press.

Schrijver, L. (2008). OMA as Tribute

to OMU : Exploring Resonances in the Work of Koolhaas and Ungers. The Journal

of Architecture. 13(3), 235-261.

Schrijver, L. (2012). Imaging the Future or Constraining the Now ? Architectural

Representation from Crisis to Boom, and Back Again. Unpublished Article,

Courtesy of the Author.

Schumacher, T. (1971). Contextualism : Urban Ideals + Deformations. Casabella. n. 359-360.

Anno XXXV, 78-86.

Somol, R. E. (1999). “Dummy Text, of the Diagrammatic Basis of Contemporary

Architecture.” Introduction to the Book :

EISENMAN, Peter. Diagram Diaries. Universe. Rizzoli international Publications.

Suh, Y. (2010). Rowe x Ungers : Untold Collaborations on the City During the 1960-70s

at Cornell. [Exposition] August 25, 2010 – August 27 John Hartell Gallery,

Sibley Dome Cornell, USA.

Teyssot, G. (1980). “Clasicismo, Neoclasicismo y “Arquitectura Revolucionaria”” Teyssot,

G. “Clasicismo, Neoclasicismo y “Arquitectura Revolucionaria””, Prologue to the

Book : Kaufmann, E. (1980). Tres Arquitectos Revolucionarios : Boullé, Ledoux y

Lequeu. (Xavier Blanquer, Marc Cuixart, Enric Granell & Ricardo Guasch

trans.) GG. Originally published in 1952.

Ungers, O. M. (1982). Morphologie. City Metaphors. Verlag der Buchandlung Walther König.

Vidler, A. (2000). Diagrams of Diagrams : Architectural Abstraction and Modern Representation. Representations, 72, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.2307/2902906

Whiting, S. & Koolaas, R. (1999). A

Conversation Between Rem Koolhaas and Sarah Whiting. Assemblage, 40, 36-55.

Yaneva, A. (2009). Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture : An Ethnography of Design. 010 Publishers.

[1] The title of the second paper:

“Iconographic condensation in the work by Rem Koolhaas, on the way from triple

dissociation concept/meaning/image to the ambivalent in-significant meaning.”

Published in Shodhkosh: Besa, E. (2023).

Iconographic Condensation in the Work of Rem Koolhaas. ShodhKosh: Journal of

Visual and Performing Arts, 4(1), 1-16. doi: 10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i1.2023.370.

Both papers are translated from the

content of two epigraphs of the chapter about Koolhaas that belongs to the PhD

thesis by the author: Besa (2015).

Arquitecto, obra y método. Análisis comparado de diferentes estrategias

metodológicas singulares de la creación arquitectónica contemporánea. Tesis

Doctoral, ETSAM UPM. OAI: http://oa.upm.es/38053/

Published as a book in Spanish: Besa (2021).

Arquitecto, obra y método: Kazuyo Sejima, Frank O. Gehry, Álvaro Siza, Rem

Koolhaas, Peter Zumthor. Diseño Editorial.

The index and the conclusion of the PhD

thesis of the author are published in English in: Besa (2017). Architect,

work, and method. IDA: Advanced Doctoral Research in Architecture. p 1157-1179

https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/70078?locale-attribute=en

[2] “AMO is a child of the 1990s, but the true origin of AMO probably dates

back to the legendary Koolhaas encounter with the Berlin Wall, in

“OMA’s place of origin is not New York, as one

might assume, but Berlin. From there the path led to Manhattan, and thus, ahead

the Delirious New York of

[3] “In 1972 I won a fellowship that enabled me to

study in the States. Before deciding, I checked out Ithaca, met first Colin

Rowe then Ungers… With the first I listened to an exciting monologue, with the

second I was involved, from the first second, in an exciting dialogue that

resumed as if there was no real interruption every time, I met him since.” Koolhaas

(2006).

This academic

reference that leads us -not only to Ungers but even- to Rowe, is unavoidable

because of its relationship with the differences of modern/traditional

conceptions of the city that are struggling within the concept of the Embassy.

Both figures,

Rowe/Ungers, are mentioned in this work about Koolhaas beyond the latent

preference of Koolhaas for Ungers and beyond the conflictive –productive?-

relationship between Ungers and Rowe. This latter controversial relationship

has been reflected in the exhibition: Suh

(2010). Rowe x Ungers: Untold Collaborations on the City during the 1960-70s at

Cornell. [Exposition] August 25, 2010 – August 27 John

Hartell Gallery, Sibley Dome Cornell, USA.

Before the time in

Cornel, both, Rowe in Texas, and Ungers in Germany, had utilized this

figure/ground inversion to represent their projects: “Exercise: scale model in which volumes of space are represented as

volumes of mass.” Caragonne

(1994), 397

“Ungers defined his

Neue Stadt Project as the archetype for a city of “negatives and

positives”-that is, a city in which the experience of form as a composition of

built and void space became the main architectural motif” Aureli

(2001), 182-184

Lara Schrijver also

analyses the influence and resonance of OMU(Ungers) in OMA’s and Koolhaas’

work. Schrijver

(2008), 235-261

[4] Caragonne (1994), 349. More references: “by the early 1970s, the

model between (…) two apparently conflicting requirements was firmly

established. As Schwartz and Fong put it, the hotel “could satisfy the disparate

requirements of the public and private realms”; that is, it could accommodate

often complex programmatic requirements while maintaining the urban fabric”.” Caragonne (1994), 349.

“In Lotus International, David Blakeslee Middelton Cornell (1979), one of Rowe’s students, describe

the philosophy guiding that studio through the 1970s: “There are at present two

major urbanistic conceptions: The traditional city –a solid mass of building

with spaces carved out of it; and the city in a park –an open meadow within

which isolated buildings are place… The potential of combining the positive

aspects of both the traditional and modern city has been the primary motivation

underlying (the studio) projects.” Caragonne (1994).

The same polarity is described in Schumacher (1971), 78-86

These two complementary understandings of the city were tested in Berlin

by the two political extremes: traditional city was tested in Stalinallee

project in East Berlin, modern city in Hansa Viertel in West Berlin. Ungers

proposed a third alternative through his Green Archipelago, which, according to

Pier Vittorio Aureli, influenced the autonomous Super-blocks that Koolhaas

developed in his first projects. Indeed, some of these islands were located on

podiums that highlighted his proposal’s autonomy, similarly to the case of the

Embassy.

These projects by Koolhaas and Ungers are not looking for the synthesis

of the above-mentioned cities, but rather they belong to the autonomy of the

modern solution. Because, far from seeking a continuity of the traditional

city, basically they come to criticize the restoration of the historical

perimeters that Krier brothers proposed. Aureli (2001), 178 They also distance themselves from the

morphological mass proposed by Rowe. Aureli (2001), 206

[5] These typologies

are also related to the two opposite notions, defined as inclusivism and

exclusivism, that Stuart Cohen tries to overcome in his critical dissertation

on Physical Contextualism Cohen (1998).

[6] These analyses also understand the interior

dissociated from the exterior while this paper understands the interior as a

direct consequence of the operations that have been made from the exterior of

the building. “There is little coordination between interior

and exterior. In the contrast between the internal vitality of

this organism and the tranquil expression of its facades, there is something

intriguing. Koolhaas’ miniature “diplomatic” village an Expressionist labyrinth

with a surprisingly informal interior realm can be compared to the reserved air

of a gentleman, who though excited never allows it to show (a diplomat for

example).” Koolhaas

(2006).

[7] Almodóvar, P. (Director). (2010). La

piel que habito [Film]. El deseo. http://www.lapielquehabito.com/

[8] This Koolhaasian Bigness term is used because similar

arguments, related to the skin and the size that are developed in the text of Conversation with Students, are also

collected by Koolhaas himself in a text with the name: “Bigness or the problem

of the large”. Koolhaas (1995).

[9] More than once Koolhaas has showed

his interest in this voyeuristic inversion through an allusion to a building he

usually refers to, the Bentham’s Panopticon. In its scheme, Koolhaas finds a

reversal of the gazes by which the prisoners are the ones who end up watching

the guard and not viceversa. This situation becomes classified as ‘very Dutch’

by Koolhaas in an-interview by Olbrist in the Architecture Biennale Olbrist (2010).

[10] "en su

cuestionamiento sistemático de la tradición, la actitud moderna rechaza la

imitación de la naturaleza y descubre en la especulación intelectual el medio

que da acceso al futuro.” Madec

(1997), 62

Another quote that justifies the development of

this analysis: “Why this change should have occurred in the middle of the

eighteenth century is not entirely clear, but it is evident that as soon as

architects became aware of architectural history, and of the architectures of

exotic civilizations (and hence of architectural ‘styles’); as soon as they

became uncertain as to which of a wide variety of tectonic elements they might

appropriately use; they were obliged to make basic decisions involving moral

judgements, and to discuss fundamental problems which their more fortunate

forbears had disregarded because in their ignorance of history, and the

security of their traditions, they did not know that these fundamental problems

existed, and hence were blissfully unaware that there were any ethical

decisions to make”. Collins

(1965), 41

[11] The quote

continues trying to relate the conceptual idea with the impression that it

triggers in our unconscious: “it must have the power to stimulate the human

emotionally, if only subconsciously”. It is a quote from the words by Ken

Boone, from the already quoted ‘Texas Rangers’ era at The Texas School of

Architecture. Caragonne (1994), 264

Other quotes from

the same page: “(…) one of the most fascinating aspects of

the new teaching as it evolved in Austin: the mysterious universal, timeless

essence of the architectural idea. (…)

“An idea,

architecturally, is the scheme or motif behind a design. It is, if handled

right, apparent in the creation itself and furnishes the reason for the design

looking as it does. A good idea is readily discernible in a building, and one

doesn’t have to ask why this or that was done in the construction of it because

the reason is obvious in the design.”

[12] “There are two kinds of beauty: free beauty (pulchritudo vaga)

or merely dependent beauty (pulchritudo adhaerens). The first presupposes

no concept of what the object ought to be; the second does presuppose such a

concept and the perfection of the object in accordance therewith. The first is

called the (self-subsistent) beauty of this or that thing; the second, as

dependent upon a concept (conditioned beauty), is ascribed to Objects which

come under the concept of a particular purpose.” (…) “the one is speaking of

free, the other of dependent, beauty, —that the first is making a pure, the

second an applied, judgement of taste.” (§ 16.: KANT,

1914)

[13] “The

Beautiful and the Sublime agree in this, that both please in themselves.” (…)

“But there are also remarkable differences between the two.” (§ XXIII.: Kant,

I. 1914)

This is the same irreconcilable crack which is

not far away from the drama that architects like Boullée confess having suffered

in their own flesh and body. “Boullée was fully aware that he aimed at discrepant

objectives. How could the elementary

geometrical shapes be reconciled with picturesqueness? He lived in the illusion

that he was able to reach the impossible, to reconcile the irreconcilable. This

is the meaning of his confession at the end of his text: “I had to fear that in

taking the way of picturesqueness. I might become theatrical. But I was anxious

not to renounce that purity which architecture demands. I believe I have

circumvented the risk of ambiguity.”” Kaufmann

(1952), 473

[14] Perrault’s

demystifying of Greek Orders: “(…) Perrault (…) afirma (…) que los principios de analogía y de

antropometría pueden, todo lo más, servir para distinguir los tres órdenes

arquitectónicos, pero de ninguna manera explicar sus reglas de proporciones.

Perrault desacraliza así el concepto de Natura, que sirve tradicionalmente de

justificación a las “reglas del gusto” (…)”. Teyssot (1980), 22

[15] “‘One must

suppose,’ he declares, ‘that there are two kinds of beauties in architecture,

those that are founded on convincing reasons and those that depend on

prejudice,’ or as he also formulates it, ‘I oppose to a beauty which I call

positive and convincing another which I call arbitrary.’ Under positive

beauties he lists ‘richness of material, the size and magnificence of the

building, precision and neatness of execution, and symmetry’, while he calls

arbitrary those beauties that ‘depend on one’s own volition to give things that

could be different without being deformed a certain proportion, form and

shape’. Those belonging to the first group are recognized and appreciated by

everyone, since by their very nature they are well defined, to such an extent that

any fault would immediately show. However, as far as the second group is

concerned, the question still remains of how it is possible that things exist

in architecture which ‘although they have in themselves no beauty that must

without fail please’ are yet pleasing to the eye.” Herrmann (1973)

[16] This concept can

be related with this text: “thinking seeks out phenomena and experiences which

describe more than just a sum of parts, paying almost no attention to separate

elements which would be affected and changed through subjective vision and comprehensive

images anyway. The mayor concern is not the reality as it is but the search for

an all-round idea, for a general content, a coherent thought, or an overall

concept that ties everything together. It is known as holism or Gestalt theory

and has been most forcefully developed during the age of humanism in the

philosophical treatises of the morphological idealism.” Ungers (1982), 7

[17] The reader might

notice the influence that Rowe receives from Wittkower, as Palladio was the

figure that Rowe compared with Le Corbusier, approaching modernity to Italian

Mannerism. But above all, Wittkower’s influence is determined by the structural

mathematic interpretation that Rowe uses to make that comparison Rowe (1976).

[18] Anthoy Vidler

links the final form of the architecture with its diagrammatic representation

in a paper that mentions Durand’s method and Wittkower’s and other schematic

representations Vidler (2000), 1-20.

[19] Both traditions

are also expressed in the following quote from a text by Alfonso Muñoz Cosme: “Una tendencia

disciplinar ha otorgado a la idea el papel de motor del proyecto, siguiendo una

corriente que tiene sus raíces en la cultura manierista, en la creación

romántica y en la tradición platónica. Así, el proceso de ideación consistiría

en la búsqueda de la idea más adecuada. (…)

Sin embargo,

en otros momentos se ha pensado que el proyecto no precisa partir de ideas,

sino de un procedimiento normado y científico, que por deducción nos permite

llegar desde las premisas de partida a la solución arquitectónica. Esto es lo

que ha sucedido en la tradición académica francesa, en determinados sectores

del Movimiento Moderno y en algunas tendencias actuales. (…)” Muñoz

(2008), 98-100.

[20] There are plenty

analyses that understand Koolhaas’ work from a cinematic perspective. They are

based on his journalism studies and his work as a screenwriter before he

started architectural studies. Among these analyses we could find Moneo’s

interpretation of Villa Dall’Ava in Paris Moneo (2004).

[21] “On the other

hand, if you are working in Europe, for instance in Berlin, context is

everything. And of course, I deeply engage with it and profoundly feel thinking

about every issue of the context. But context is of course also political, is

not only the physics.” Words

by Koolhaas on the video: Heidingsfelder

& Tesch (2009).

Also see: “The Terrifying

Beauty of the Twentieth Century”, in Koolhaas (1995), 204-209.

[22] The critique by Dovey and Dickson also ends up with a question about

the voluntary nature of some of the connotations that can be found in the work

by Koolhaas: “Is this new spatial hierarchy an accidental by-product of

Koolhaas’ obsession with the elevator? Or is it a deliberate tactic of bringing authority into the light rather

than resisting it (…)” Dovey

& Dickson (2002), 13

[23] Derrida describes

architecture as the last fortress of metaphysics: “For Derrida these tangible

factors conspire to render ‘architecture as the last fortress of metaphysic’.” Coyne (2011), 60. The factors, that this quote refers to, are

related with the concept of dwelling, nostalgia of origin, human service, harmony,

and beauty. These statements by Derrida have a direct relation with Koolhaas’

attempt to deny any trace of precedent morality in architecture.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2023. All Rights Reserved.