ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Iconographic condensation in the work of Rem Koolhaas. On the way from triple dissociation concept/meaning/IMAGE TO the ambivalent in-significant meaning

1 Teacher

at IDarte, Basque School of Art and Higher School of Design,

Spain

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This article shows the

attempts and struggles of recent architecture to reconcile the question of

meaning (also image) with the abstract and schematic structure of modernity.

This is a question that architecture has apparently not yet managed to

synthesize, hence the interest in addressing this issue. With this aim, the study

follows the trace of Koolhaas’ controversial interest in meaning, starting

from the semantic conglomeration of his first works, which are a re-appropriation

of avant-garde elements. Then this paper continues with the analysis of

Zeebrugge Terminal and the latest iconic buildings of the last decade

(2000-2012) which represent an iconographic condensation in the work of

Koolhaas, a communicative wholeness which recovers iconicity through its

unity. The paper will follow

Koolhaas’ trajectory until its latest (2013) contradictory re-adoption of

illuminist rational and neutral language. An apparently unexpected swerve

which in fact shows that Koolhaas’ approach to iconography was less

interested in the question of meaning but rather in the intention of

perverting it. Therefore, the method of

this article is based on a descriptive route through some of Koolhaas' works.

This route is accompanied by certain references that advocate iconic

architecture, Jencks

(2006/2007), Van Berkel & BOS (2006/2007), or show an interest in diagrammatic architecture, Somol (1999). At the same time, this study includes the curious

comparisons of the book: Morphologie, City

Metaphors by Ungers

(1982), Koolhaas' indisputable referent. The study ends

with a comparison of the ways in which Koolhaas and Venturi claim, each in

his own way, the iconic and signifying recovery in architecture. Regarding

this question of research method, the suggestive character of the content of

this text is rooted in and based on the systematic and precise study of the

previous article on the Dutch Embassy in Berlin by Koolhaas.[1] This previous article constitutes a thorough deconstruction of the

building of the Embassy, which the author recommends reading beforehand. |

|||

|

Received 22 March 2023 Accepted 15 June 2023 Published 28 June 2023 Corresponding Author Eneko

Besa, enekobesa@idarte.eus, enebed@gmail.com

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i1.2023.370 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2023 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Iconic Condensation, Semantic Iconography,

Connotative Meaning, Ungers, Venturi |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Koolhaas referring to the Berlin Wall:

“It was

clearly about communication, semantic maybe, but its meaning changed almost

daily, sometimes by the hour. It was affected more by events and decisions

thousands of miles away than by its physical manifestation. Its significance as

a “wall” –as an object- was marginal; its impact was utterly independent of its

appearance. (…) I would never again

believe in form as the primary

vessel of meaning.” Koolhaas et al. (1997), 227 (The three words are underlined by the author, and they refer to the

concepts that the previous paper found dissociated in the Embassy building.)

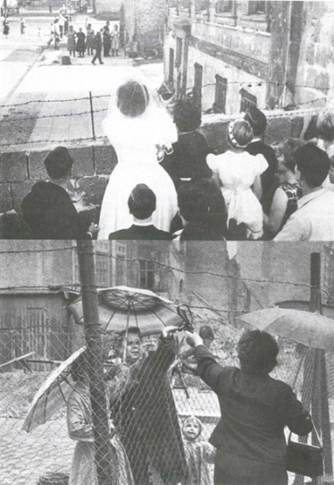

Through the above words about The Berlin Wall, Koolhaas assumes the fracture, the fact that the meaning in architecture does not exist outside the fracture with its form, and even with its image. Figure 1. A previous paper about the Dutch Embassy, which is located in the same context of the Berlin Wall, showed how this triple rupture between meaning/form/image can also be found, not only in an unparalleled manifestation such as the Berlin Wall, but also in a building. Figure 2, Figure 3 Thus, both the Wall and the Embassy, constitute an example of how dissociated conceptual structure and its connotation can be.

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 The Berlin Wall in

S, M, L, XL. Images used by Koolhaas to show his thoughts about the Wall Source KOOLHAAS,

Rem. MAU, Bruce. OMA. S, M, L, XL. The Monacelli Press, New York 1995. |

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 The Dutch Embassy

and its Surroundings (2004) Source http://duitsland.nlambassade.org/organization/de-ambassade/het-ambassadegebouw

|

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 The Dutch Embassy, Open Courtyard Source http://duitsland.nlambassade.org/organization/de-ambassade/het-ambassadegebouw |

Through the interest in this dissociation, Koolhaas shows his controversial comprehension of the question of meaning and sense in architecture. He does this in such a way that positions him within a philosophical stream for which the meaning does not represent any other transcendent content further than its intrinsic conflict.[2] That controversial attitude towards meaning is where Koolhaas finds a springboard to launch his statements about the loss of morality and any other metaphysical content in architecture.[3]

Nevertheless, this paper represents a counterpart to the previous one on the Embassy, as it is based on the fact that this ambivalent relationship with the notion of meaning eventually reveals Koolhaas’ interest in it. Thus, his very critical position regarding semantics constitutes the meaning as the fundamental reference, even in its conflictive condition. In fact, not only from his interpretation of the Wall or thanks to a recent building like the Embassy, but also through his early works Koolhaas found a position within the gap of the equivocal relation between meaning, form, and image.

Viewing his early works, the morphology of their components, volumes, and structural elements, will show that they are full of allusions to the avant-garde language, particularly the Russian constructivist vanguard. Figure 4. Indeed, this usurpation of the avant-garde elements is mainly focused on their signifying condition rather than their function, their constructive or economic requirements. These elements are not even going to respond to the ideology they come from, but rather Koolhaas re-uses these signifiers embedding a new connotation within them.

Figure 4

|

Figure

4 Theatre in the Hague

(1987) Source Author |

Thus, these allusions to the vanguard elements are made by

a suggestive re-appropriation of their connotation. They acquire a new semantic

condition through Koolhaas’ reinterpretation, becoming icons of the modernity

they arose from. With this playful game of avant-garde elements, Koolhaas

reveals his own interest in the question of the communication of architecture,

since the same ambiguous condition of meaning, which is at stake in the

re-appropriation of these elements, alludes directly to their signifying

communicative condition.

Nevertheless, this interest is not limited to each element that Koolhaas readapts, but rather their gathering reaches a wholeness in which they can even bind with each other, overlap, and superimpose themselves onto the overall shape of the building, reaching an unstable equilibrium of a constructivist composition. Figure 5 Thus, this eloquent connotative expression is not only based on each element’s suggestive mission, but rather their controversial relationship offers a new dialectical unity, i.e., an opposition and a conflictive allusion between their differences through which Koolhaas achieves a tense communicative unity.

Figure 5

|

Figure 5 Theatre in the Hague (1987). Source Author |

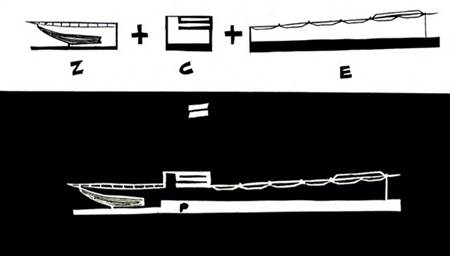

In this same contraposition Koolhaas finds a new conceptual unity out of the juxtaposition of disparate and contradictory elements, as is shown in the model of the Cardiff Bay Opera House. Figure 6 This is a solution which is close to the dialectical relationship that combines the heterogeneous parts of the Congrespo in Lille under a single curved cover. This can also be found in the different combined volumes within the model of the Educatorium in Utrecht, or in the interior of the Agadir Convention Centre. Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10

(Koolhaas talking about the Bigness) “Such a mass can no longer be controlled by a single architectural gesture, or even by any combination of architectural gestures. This impossibility triggers the autonomy of its parts, but that is not the same as fragmentation: the parts remain committed to the whole.” [4] Koolhaas (1995), 499-500

Figure 6

|

Figure 6 Cardiff Bay Opera House (1994) Source OMA |

Figure 7

|

Figure 7 Congrespo in Lille, Schematic Section (1994) Source

OMA |

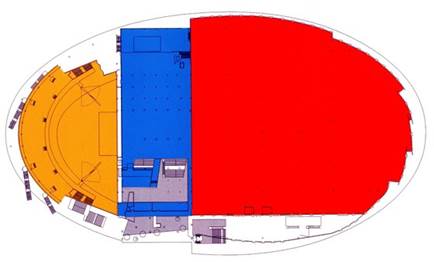

Figure 8

|

Figure 8 Congrespo in Lille, Plan (1994) Source OMA |

Figure 9

|

Figure 9 Educatorium in Utrecht, Model (1994) Source OMA |

Figure 10

|

Figure 10 Agadir Convention

Centre (1994) Source OMA |

However, through this ‘contra-positional com-position’, these buildings are unveiling their inability to integrate all the contradictions in a non-dialectical unity. Therefore, these buildings are essentially revealing a disillusioned nostalgia for the ‘lost unity’.

“I have certain nostalgia for “a one”. One of the reasons of my endless preoccupation with Mies van der Rohe is that, how somebody could find the same answer for every issue. And you could say to me that the books of Mies have got a kind of single universal answer. (...) I don’t think we can do it.” Heidingsfelder & Tesch (2009) (Words from an interview with Koolhaas from the video).

Nevertheless, contradicting his trajectory and even his own words, Koolhaas reaches a coherent conceptual unity in some of his buildings, as the previous paper about the Embassy demonstrated. Not only the Embassy, the ZKM project in Karlsruhe also shows a conceptual and structural compactness which is even more condensed than the coherence analysed in the Embassy.

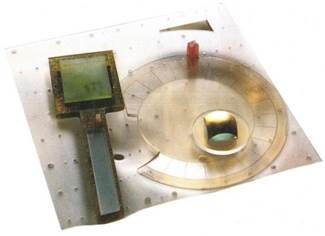

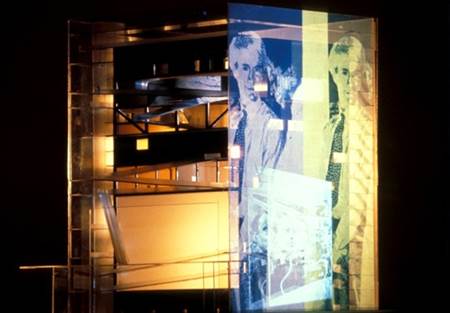

However, in the ZKM project we can again find a

dissociation which, in this case, could be not far from the theories about the

‘vertical schism’ between interior and exterior shown in Delirious New York. Despite the ZKM's interesting inner structural

solution based on Vierendeel beams, it acquires its communicative status from

the projections (that exist) over the metallic screen that is wrapped round its

entire volume. Thus, the ZKM project gains its iconographic message only when

its exterior denies its inner structural order. Figure 11

Figure 11

|

Figure 11 ZKM Building (1992).

Dissociation Between Interior and its Exterior Shed Source OMA |

Another building which presents this conflictive

relationship between its conceptual structure and some of its expressive

features is the Kunsthal in Rotterdam. It can be

classified within the same category as the Embassy and the ZKM project as it is

one of the buildings that shows a coherent consistency, in this case, due to

the system of ramps and inclined slabs that Koolhaas uses to build its

conceptual scheme. Figure 12

Figure 12

|

Figure 12 Kunsthal, Conceptual Scheme (1992) Source OMA |

However, once Koolhaas reaches such a structural

consistency, he eventually perverts its mechanical structure by building the

pillars of the Kunsthal out of contradictory

materials and shapes. To the extent that, in the very confined space of its

porch, the extreme diversity of the following list of pillars coexists: a

concrete pillar which is X-braced to a steel honeycomb pillar, an “H” laminated

steel pillar and a Miesian “+” shaped laminated steel pillar. A little further

on, and in the same porch, circular concrete pillars also coexist with the

previous list of pillars. In addition to this variety, wooden trunk coated

pillars can also be found in the interior of the building. Figure 13

Figure 13

|

Figure 13 Kunsthal, Image of the Pillars of the Porch (1992) Source Courtesy

of Tim Mechielsen |

With this bold attitude, Koolhaas dares to contradict the natural physical law by which all pillars and support systems of a structure should be built with the same elasticity and formal characteristics in order to ensure equal deformation and avoid differential movement and the resulting cracking.

Therefore, what these pillars are trying to tell us is that they achieve their meaning only when they contradict, and they dissociate themselves from the unity of the structural system which they belong to. Thus, these pillars acquire a singular connotation due to their differential formulation, which leads once again to the ‘lost unity’, and also, to the impossible link between concept/meaning which we are referring to over and over. Intrinsically, these conclusions demonstrate the very controversial essence of meaning, as they show that significance is only achievable through the renouncing of the compositional and conceptual unity.

This could be the reason why, due to the impossibility of

reaching a signifying compositional wholeness, Koolhaas seeks a new connotative

unity through the juxtaposition of different overlapping elements in the

buildings mentioned previously. This strategy is applied to extremes that can

also be observed in more recent works such as the house in Bordeaux, where

Koolhaas reaches a risky unity through the violent counterweight which tightens

the diverse overlapping plans of the project. Thus, Koolhaas yields a

communicative unity through the suggestive, and at the same time disquieting, dialectic

of very contrasting elements. Figure 14

Figure 14

|

Figure 14 House in Bordeaux.

Structural Scheme (1998) Source OMA |

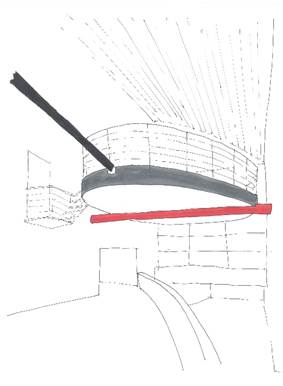

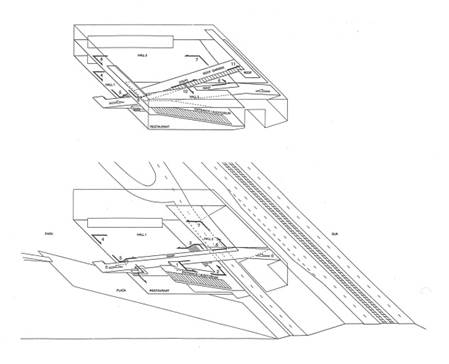

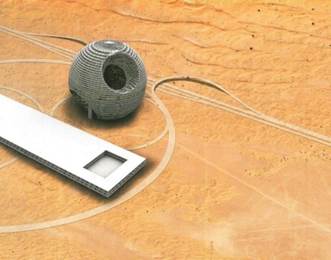

However, and even before the house in Bordeaux (1998), the

Zeebrugge Terminal project (1989) finds an alternative to this multipolar

fragmentation, since the different parts of the interior of the Terminal are

wrapped in and coated by a shell which provides a new unitary profile. Figure 15 The skyline of

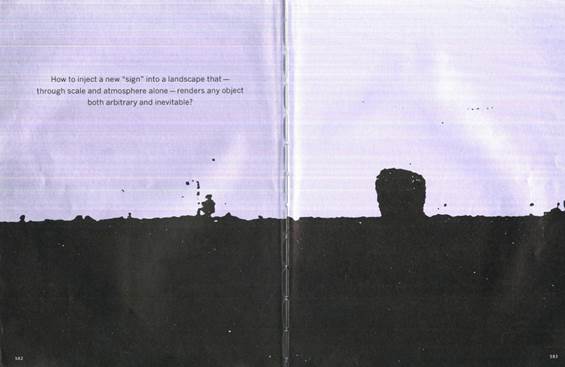

Zeebrugge city makes the profile of this project understandable. In fact, the

drawing that Koolhaas published in SMLXL shows the origins of its peculiar

shape, since it expresses the building’s need to stand out from its magmatic

background of cranes and other port elements. Figure 16

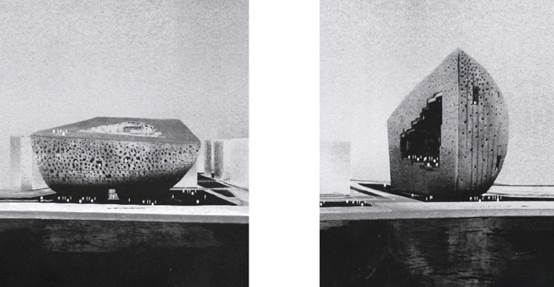

Figure 15

|

Figure 15 Zeebrugge Terminal, Model

(1989) Source OMA |

Figure 16

|

Figure 16 Zeebrugge Terminal’s

Profile in S, M, L, XL (1989) Source KOOLHAAS,

Rem. MAU, Bruce. OMA. S, M, L, XL. The Monacelli Press, New York 1995 |

Nevertheless, a closer look at the building, at its structural elements, its beams, its holes, and its interior components, shows that not only the shape of the building but also all its elements are semantically impregnated. Unlike the above-mentioned buildings, the ones that we called ‘contra-compositional’ buildings, Zeebrugge Terminal reaches an iconographic unity which incorporates all its intervening components, and at the same time each element also acquires a specific semantic condition.

In this case, even the structural trusses, which are elements that have usually been defined by their specific constructive entity, become a pop image of themselves through their fusion with the silhouette of the terminal. This is done in a way where they can be understood as holes in the building’s envelope rather than added bars that support it. Thus, the expression of this connotative silhouette becomes the main argument that integrates all the elements of the building, turning Zeebrugge Terminal into a significant icon which can even transform its surroundings.[5]

Therefore Zeebrugge’s profile, although belonging to the same period of time as the fragmented contra-positional buildings described above (80s-90s), also constitutes a premonition of some of OMA’s more recent iconic projects (2000s), e.g. such as the Hafencity in Hamburg, the CCTV and TVCC buildings in Beijing, the Koningin Julianaplein in The Hague, Project ‘S’ in Seoul, the Whitney Museum Extension, the Astor Place Hotel, The Twins in Tunisia, the Torre Bicentenario in Mexico, Seattle Library and so on. Figure 17, Figure 18

(Other projects by OMA also reach an iconographic wholeness, although their profile does not show the formal unity of the former: Gazprom headquarters, La Défense Project Phare in Paris, De Rotterdam building, Córdoba Congress Centre and so on).

“We often joke: we say that we have two lines like the Nike lines: OMA classic and OMA swoosh. And OMA swoosh comprises projects like PORTO, so the new line is when the form is much more expressive than the classic. Seattle is almost the end of OMA classic. And if you look at Cordoba, it’s all new line. It can be a model; it can be a diagram.” Yaneva (2009), 35

Figure 17

|

Figure 17 Project S in Seoul (2004) Source OMA |

Figure 18

|

Figure 18 Torre Bicentenario in México City (2007) Source OMA |

All of these are projects that tend to become authentic urban landmarks through their iconographic condition. Indeed, due to this iconic unity, the elements and parts that constitute the building, not only blend into the silhouette as in Zeebrugge, but they also disappear as they sacrifice themselves for the sake of the unified global image that conceives these buildings.

“(…) as Koolhaas says, OMA’s recent projects are bodies rather than objects.” Graafland (1996), 43

In fact, through these iconic buildings, architecture finds a new morphology which frees itself from its traditional elements. Thus, in these iconic buildings, we cannot recognize any cubic or other geometric shape, neither trusses nor pillars, even less architrave, molding or other architectural joints, whether they are classical, modern or postmodern. Some of these buildings are even susceptible to being overturned, making an explicit reference to their independence with respect to traditional architectural language: vertical/horizontal, gravity/levity, light/shadows, etc. Figure 19, Figure 20 Some of these iconic buildings even identify themselves with the foam from which their model was made. And thus, the thickness of the sponge and the girth of the silhouette itself absorb all these iconic building’s requirements and contingencies, allowing architecture to reach the expression of a new graphical syntax. Figure 21

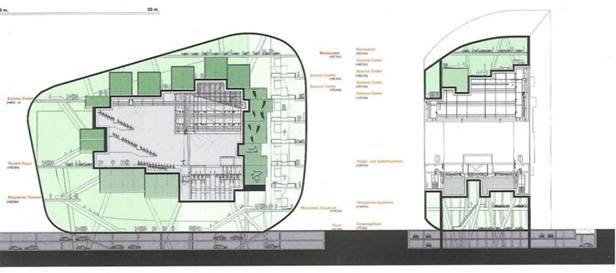

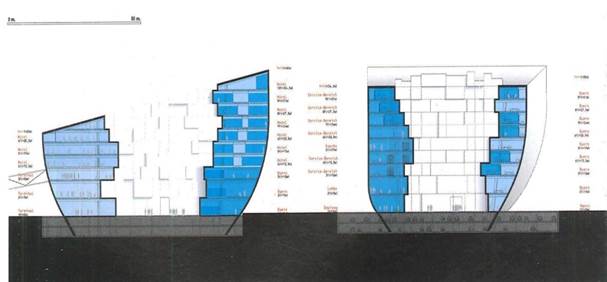

Figure 19

|

Figure 19 Hafencity in Hamburg. Models

(2004). Source OMA |

Figure 20

|

Figure 20 Hafencity in Hamburg. Sections (2004) Source OMA |

Figure 21

|

Figure 21 Astor Place Hotel (1999) Source OMA |

The warps, the bends, the inclination of the planes which section the profile of the figure, the relationship between flat surfaces and warped surfaces…. the reader will notice that all these words do not refer to components or elements, but to formal characteristics. In fact, these iconic buildings are no longer constituted of parts or elements, but rather by the successive formal operations that are performed on their profile until they get a convincing iconographic image.

“(…) you just

look at the piece of foam and you try to make it beautiful, you cut. Sometimes

you slice something, and then, another thing, and ou-u-u-p-p-p

something is there. And you

think” “Oh, that’s interesting”: it’s there (…).” Yaneva

(2009), 57

“We come across buildings in which every single perceptible feature serves one prevailing concept. Get it, and there is nothing more to discover, nothing to effectuate protracted attention.” Van Berkel & BOS (2006/2007), 44

“Claude Parent: In those days it was possible because the primordial material of the architect was still the notion of space. This war is now over, it’s prehistoric! In our day, we didn’t focus on space. The materials and the medium of the new generation have completely changed.

Hans Ulbrich Obrist: What are they working on today?

CP: Other

things. They work on and through the image. The architects who worked on space

–deforming it or not- are from the 1960s. This time is now over.” (Koolhaas (2006), no pages in the publication)

As the previous quote shows, the spatial condition of architecture and its consequent abstract structure is replaced by the interest in a new iconic image. Therefore, these buildings are created through a sophisticated development of their iconic profile, reaching a representative unity through their image. Thus, contrary to the early buildings of his career, these later buildings are not constituted by a pop re-appropriation which makes modern elements figurative. Indeed, the image of these buildings is not achieved by an amalgam of existing forms; on the contrary, their form is a direct consequence of their synthetic image.

“As the

meaning of a whole sentence is different from the meaning of the sum of single

words, so is the creative vision and ability to grasp the characteristic unit

of a set of facts, and not just to analyze them as

something which is put together by single parts. (…)” Ungers (1982), 8

Unlike the split between image and formal concept that can be found in other buildings like the Dutch Embassy or the Kunsthal, these iconic buildings show the unity, the immediate apprehensibility of their image. In fact, the specific characteristics of these iconic shapes are not detached from the wholeness of the general image of the building. This is a conclusion which leads us to conclude that these buildings have been designed through a global condition which could be closed to the condensed and synthetic perception of our visual sense.

“That relating exercise is what the eye and brain do, when confronted by a shockingly different building. They map new onto old visual codes. This instant and largely unconscious process produces the metaphor in Foster’s skyscraper, the tabloid one, “it looks like a gherkin” and public and journalistic excitement.” Jencks (2006/2007), 52

Based on this, it could be said that these buildings relink Kantian dissociations between image and concept -which the previous paper showed. This reconciliation is achieved through the discovery of the symbolic entity of these buildings’ image.

“In every human being there is a strong metaphysical desire to create a reality structured through images in which objects become meaningful through vision.” Ungers (1982), 8.

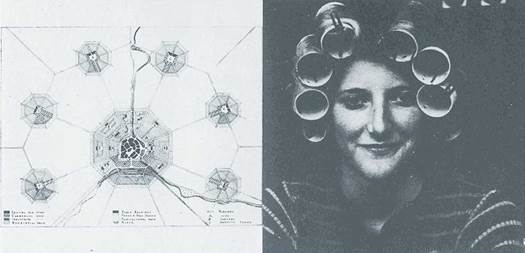

This quote, as in the previous paper, comes from Ungers’ thinking, and in this particular case, from his book Morphologie. City Metaphors. In that book Ungers surprisingly associates the schematic representation of urban plans with figurative images of everyday life that he finds similar.[6] Figure 22 And so, the perplexity that Ungers makes us feel when he matches a city plan with an image of a woman with curlers in her hair, comes to question the negative connotation of the visual, the disengagement between images and ideas that characterizes western culture.[7] Thus his attempt tries to link the conceptual structure and its image, which has been inevitably dissociated since Kant. Because what Ungers achieves through his matched pair of images is to associate certain visual characteristics of figurative reality with the conceptual schemes that reveal the internal structure of buildings and cities. Basically, he re-binds the image with the concept that it represents.

Figure 22

|

Figure 22 Pairs of Images that Ungers Matches in His Book: Morphologie. City Metaphors (1982) Source UNGERS, O.M.

Morphologie. City Metaphors. Verlag der Buchandlung Walther König, Köln 1982 |

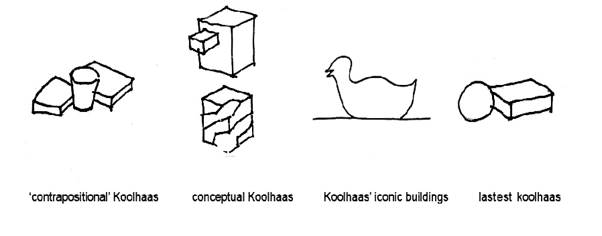

As the above iconic buildings have shown, Koolhaas

prolongs Unger’s attempt, reaching the identification of the concept with the

visual figuration that his models accomplish. This occurs to such an extent

that the schematic profile of these buildings itself becomes so figurative that

it constitutes a caricature of its architecture, as the parodic drawings by

Simon Brown show. Figure 23

Figure 23

|

Figure 23 Caricatures of

Koolhaas’ Buildings by Simon Brown (Content, 2004) Source KOOLHAAS,

Rem. McGetrick, Brendam. (ed) &&&

Brown, Simon. LINK, Jon. Content. TASCHEN GmbH. Koln 2004 |

Nevertheless, if we believe that the buildings above reach the synthesis that Ungers pointed out, then these iconic buildings also resolve the dissociation and contradiction through which Venturi openly positioned himself, since Venturi did not seek any kind of integration, but rather, contrary to Ungers’ metaphors and Koolhaas’ iconic buildings, his well-known ‘decorated shed’ scheme came to proclaim the definitive gap between conceptual structure and its iconographic significance. Figure 24

Figure 24

|

Figure 24 Decorated Shed by Robert Venturi (Learning

from Las Vegas, 1977) Source VENTURI,

Robert. IZENOUR, Steven. SCOTT BROWN, Denise. Learning from Las Vegas: The

Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology Press, Cambridge 1977 |

Actually, after the proclamations of Venturi’s manifesto, architecture was never going be unified. It was going to stop being a ‘duck’, i.e., its conceptual form would definitively fail to express its meaning. Rather, architecture would always be a ‘decorated shed’, in which the meaning would be represented by a superimposed pop screen over architecture’s functional and structural systems, indeed over its real constitution.

Thus, the weakness of Venturi’s iconographic layer could be one of the most important reasons for the failure of postmodernism, as it never succeeded in transforming modern structural conditions, it merely overlapped them.

“The demise of twentieth-century aesthetic which promoted a universal architecture as expressive space, industrial structure, and functional form and which has lately been spiced with chic distortion, hype coloration, cute symbolism, and heroic theory:

Hey, what’s for now is a generic architecture whose technology is electronic and whose aesthetic is iconographic –and it all works together to create decorated shelter – or the electronic shed!” Venturi (1996), 11

As the above quote by Venturi shows, he accepts the generic condition of modern times, he implicitly assumes systematic functionality and he superimposes an iconographic signifying layer which has no interaction with the structure that it covers.[8] And so, his architecture claims a concept which is similar to the universal generic mobile phone, over which any teenager –or not so teenager- can overlay a shell, which functions as an image that reaffirms his/her identity conflicts through its iconographic representation. Through this idea, Venturi sought to criticise the modern buildings that he called ‘ducks’.

Thus, Venturi defined modern buildings as ‘ducks’ as he was interested in making a caricature of modern buildings that had obtained their formal iconography through the sincere expression of their interior function. Venturi’s clearest example was a building which gained the shape of a duck to represent a restaurant that sold ducks.

However, Venturi was wrong when he described modern

buildings as ‘ducks’, because modernity was not

intending to arrive at an image of a duck in its buildings, instead it was

trying to express the functional structure of the restaurant that sold ducks. So,

the attempt of modern buildings was less to show the icon in their figure, but

rather, they were trying to obtain a significant range for their conceptual

structure. Thus, their interest in their functional structure’s meaning was

less focused on its iconography but rather on the explicit expression of their

own abstraction. Therefore, modern buildings were not as ‘duck’ as Venturi

defined them; since they were not generated aiming at their iconographic

possibilities, but they were conceived through their functional and structural

abstraction. Figure 25, Figure 26

Figure 25

|

Figure 25 Open Air School in Amsterdam

by Duiker and Bijvoet (1927-1930)

Source Author |

Figure 26

|

Figure 26 Crawford Manor, by

Paul Rudolph, as Published by Venturi Referring to it as one of the ‘Ducks’

of Modernity. (Learning from Las Vegas, 1977). Source VENTURI,

Robert. IZENOUR, Steven. SCOTT BROWN, Denise. Learning from Las Vegas: The

Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology Press, Cambridge 1977 |

On the contrary, Koolhaas’ iconic buildings aim at the

iconographic expression that modernity denies, which leads us to the conclusion

that the iconic buildings by Koolhaas, are properly more ‘ducks’ than the

‘ducks’ which Venturi alluded to. As it has been discussed here, Koolhaas’

buildings go beyond modern buildings, since their expression is achieved

through their own formal iconography rather than through the expression of

their own structural coherence. Nevertheless Koolhaas, not only reintroduces

the ‘lost iconography’ that postmodernity claimed, but also, he achieves a

condensed communicative unity which surpasses Venturi. Table 1, Figure 27

Figure 27

|

Figure 27 Re-adaption

of Venturi’s Decorated Shed Source A

re-adaption by the Author of Venturi’s Decorated Shed |

Table 1

|

Table 1 The First Two Columns of the Table Show the Comparison of Terms that Venturi Used to Distinguish Himself from the Previous Modernity. A Column has Been Added to Define Koolhaas’ Substantive Progress with Respect to Both, Modernity and Venturi |

||

|

MODERN |

VENTURI |

KOOLHAAS |

|

20s-50s |

60s |

90s-2000s |

|

expression |

meaning |

meaningful expression |

|

Implicit “connotative”

symbolism |

Explicit “denotative”

symbolism |

Explicit “denotative”

conceptual symbolism |

|

Expressive ornament |

Symbolic ornament |

Conceptual ornament |

|

Integral expressionism |

Applied ornament |

Applied expressionism |

|

Pure architecture |

Mixed media |

Mixed architecture |

|

Unadmitted decoration

by the articulation of integral elements |

Decoration by the

attaching of superficial elements |

Unadmitted decoration by

the articulation of differential elements |

|

Abstraction |

Symbolism |

Symbolist abstraction |

|

“Abstract

expressionism” |

Representational art |

Conceptual

representation |

|

Innovative architecture |

Evocative architecture |

Subversive architecture |

|

Architectural content |

Societal messages |

Societal architecture |

|

Architectural articulation |

Propaganda |

Architectural -architect’s?

- propaganda |

|

High art |

High and low art |

Low art and high

architecture |

|

Revolutionary, progressive, antitraditional |

Evolutionary, using historical precedent |

Revolutionary, a-progressive, anti-precedents |

|

Creative, unique, and

original |

Conventional |

Originally

conventional |

|

New words |

Old words with new meanings |

new meaning for already old New Words |

|

Extraordinary |

Ordinary |

Extraordinarily

ordinary |

|

Heroic |

Expedient |

Shrewd |

|

Pretty (or at least

unified) all around |

Pretty in front |

Not Pretty but

iconographic |

|

consistent |

inconsistent |

Inconsistent consistency |

|

Advanced technology |

Conventional technology |

Tortured technology |

|

Tendency toward megastructure |

Tendency toward urban sprawl |

Tendency toward architectonic urban icons |

|

Tries to elevate

client’s value system and/or budget by reference to Art and metaphysics |

Starts from client’s

value system |

Goes further from client’s

value system |

|

Looks expensive |

Looks cheap |

Expensive trying to look cheap |

|

“Interesting” |

“Boring” |

Interesting boringness |

|

Source A re-adaption by the author of Venturi’s theory |

||

(The first two columns of the table of figure 27 show the comparison of terms that Venturi used to distinguish himself from the previous modernity. A column has been added to define Koolhaas’ substantive progress with respect to both, modernity, and Venturi).

Thus, Koolhaas takes Venturi further in so far as his

buildings are no longer covered with a shed, neither do they have a shell that

wraps their original structural form, but rather their form is identified with

their profile. In fact, even though his iconic buildings are modelled as if

they were domestic electronic appliances, their profile is not dissociated from

the mass of their inner architecture, as is shown in the section view of Hafencity in Hamburg. Figure 28

Figure 28

|

Figure 28 Hafencity in

Hamburg. Sections (2004) Source OMA |

However, this section of Hafencity in Hamburg leads us to challenge the way these two elements −architecture and its profile, formal structure, and its image− have been integrated. This is a question which brings us back again to Ungers’ metaphors, because unlike them, Koolhaas’ iconic buildings do not link a common image with their structural scheme, but rather, their image is identified with their form. In fact, in Ungers’ case, each figurative image was associated with the schematic plan of a city, unlike Koolhaas’ iconic buildings, whose formal profiles have been conceived using models that do not necessarily correspond with the schematic representation of their plans.

Thus, Koolhaas moves away from Dutch structuralism and from its interest in reducing the form to the schematic structure of the building. Indeed, the case of Koolhaas’ iconic buildings represents the inverse situation, since their schematic structure is subjugated –or at least, dissociated again- for the sake of their formal unity. This subtle distinction between formal structure and schematic structure reveals that these buildings have not achieved the synthesis which they seem to suggest, which could be the reason for the complexity they show when they are condensed into a structural scheme in order to be built.

In fact, some of these buildings show a clear dissociation between their form and their mechanical structure (Seattle, A Casa da Música). Others, like the CCTV building in China, try to merge form and structure through a clever use of computational power to calculate mechanical forces, since they even identify computer graphics with the distribution of the structural bars of their façade. Figure 29. Therefore, a building like the CCTV seems to achieve a synthesis which eventually depends on the internal operations of a computer, since its results have not even been corrected or systematized by a later adjusting analysis, but rather they have been directly translated to the façade, deliberately showing the irregular mechanical forces that are generated due to this building’s singular shape.

Figure 29

|

Figure 29 OMA, CCTV

Headquarters. (2002). Source OMA |

Thus, the CCTV building represents a curious attempt to merge structure and shape, while buildings like Seattle or A Casa da Musica show a structure which collides violently with their inner spaces and does not match these buildings’ exterior profiles. All these examples show a constructive complexity which reveals that their mechanical structure has not been taken into consideration from the very beginning of their conception. This means that their synthesis between image and form has been achieved thanks to the initial oblivion of schematic structure which eventually violently reappears in the final resolution of these buildings.

Thus, we can suspect that their iconic synthesis depends on their constructive complexity. This means that these buildings are determined by the economic excess that is implied in their construction, as also happens in many other buildings by Koolhaas. Thus, these buildings essentially prove to be sons of their time, ultimately, they show that they are a consequence of 90s’-2000s’ economic boom. So, the flamboyant economic conditions that these buildings need to feed their formal excess are totally dependent on the same market forces which led them to their iconic ambitions.[9] This is perhaps the reason why Koolhaas’ more recent buildings take a step back to a more restrained line:

“I am really nauseated by the current

over-production of icons, at the expense of all other potentials. I really

think the current idolatry of architecture causes an accumulation of bad faith.

We have to find a way, short of totally withdrawing,

of reinventing plausibility for architecture, so we have been designing a whole

range of unbelievably simple, uninflected, radically neutral buildings.” (Words by Koolhaas from an interview

in February 2007. The reader might notice that the interview takes place just

the year after the buildings in Dubai were designed, the ones that the

following paragraphs refer to. Koolhaas (2007),

352

Through the previous words, Koolhaas might be referring to

a moderate line of buildings like Rothschild Bank in London which constitutes

an interesting synthesis between sobriety and the iconographic character that

it achieves despite its Miesian formal restraint. Figure 30

Figure 30

|

Figure 30 Rothschild

Bank in London (2006) Source By the author |

However, it seems that Koolhaas is referring to the neutral rationality of the buildings designed in Dubai, the Porsche Towers, and the RAK Renaissance Gateway, all from 2006. They are all buildings that deny –or at least try to deny- their iconographical condition through a revival, and even emulation, of the pure abstraction of the architecture of the Enlightenment. Figure 31

Figure 31

|

Figure 31 RAK Convention and Exhibition Centre (2006). Source OMA |

“This project

-OMA writes (referring to the building in Dubai)- represents a final attempt at

distinction through architecture: not through the creation of the next bizarre

image, but through a return to pure form. Invented long ago, both the sphere

and the bar explicitly abandon claims to formal invention or ‘originality’.”

quoted in: Gargiani (2008), 333

This reference to the architecture of the 18th century might be seen as unusual at this point in this dissertation, and especially it could be judged unconceivable at this stage of Koolhaas’ own work. However, although this is an ‘apparently’ unprecedented reference, this contradictory attitude to his own career is more consubstantial to Koolhaas than we could ever imagine. Because in essence, through this unexpected turn, Koolhaas contradicts the iconic trend which was commonly widespread throughout the architectonic world. This shows that, despite being one of those responsible for this general trend, he does not feel comfortable following it, maybe because he is not the first anymore.

When Sarah Whiting asks Koolhaas about his influence on certain aspects of Dutch architecture, Koolhaas answers: “This trail of debris is revolting, torture. Can you have influence without following? I haven’t seen anyone who has been able to produce work that once it is received with interest resists cloning. For us, we have been obliged to eliminate from our repertoire whatever component was the victim of dissemination. (Maybe the interest in obscenity is also an interest in remaining indigestible.).” Whiting & Koolaas (1999), 53

But above all and most importantly, with this re-adoption of modern abstraction Koolhaas sweeps away any integral meaning that his work could have been acquiring and he denies the semantic meaning and the connotation which he has been playing with since he began his career. Thus, opening a new path that contradicts the work done so far, Koolhaas avoids any progress toward a whole synthesis that would surpass the achievements of his own findings.

Therefore, Koolhaas basically destroys any attempt to achieve total consistency and reveals that his interest in meaning was no more than the intention of perverting it. Through these conclusions Koolhaas is unveiled as a true sign of our times, a figure and a position which is not accidental but has been created and even fed by itself. Figure 32

Figure 32

|

Figure 32 Different Facets of Koolhaas’ Strategies as Far as

Iconographical Expression is Concerned. Source A re-adaption

by the Author of Venturi’s Decorated Shed that Makes Expressive Koolhaas’ Different

Facets |

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Besa, E. (2015). Arquitecto, obra y método. Análisis comparado de diferentes estrategias metodológicas singulares de la creación arquitectónica contemporánea. Tesis Doctoral, ETSAM UPM. OAI.

Besa, E. (2017). Architect, Work and Method. IDA : Advanced Doctoral Research in Architecture. The Index and the Conclusion of the PhD Thesis of the Author are Published in English, 1157-1179.

Besa, E. (2021). Arquitecto, obra y método : Kazuyo Sejima, Frank O. Gehry, Álvaro Siza, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Zumthor. Diseño Editorial. Published as a book in Spanish.

Besa, E. (2022). #eindakoa (what we have done) : A Pedagogical Method of Interior Design Studio Method. Journal of Design Studio, 4 (2), 179-202. https://doi.org/10.46474/jds.1207503.

Besa, E. (2022). Dynamics-Aktion- Pedagogical Dynamics Proposal, Useful for Design Studio Teaching and Beyond. ShodhKosh : Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, 3(1), 349-377. https://doi.org/10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i1.2022.118.

Besa, E. (2022). Dynamics-aktion II : Propuesta de dinámicas pedagógicas, útiles en el taller de proyectos de diseño y más allá. i+Diseño. Revista Científico-Académica Internacional De Innovación, Investigación Y Desarrollo En Diseño, 17, 103-130. https://doi.org/10.24310/Idiseno.2022.v17i.14549.

Chaslin, F. (1999). “The Gay Disenchantment” Published in OMA Rem Koolhaas. Living. Vivre. Leben. Arc en reve. Centre d’Architecture/ Birkhauser Verlag.

Chaslin, F. (2004). The Dutch Embassy in Berlin by OMA / Rem Koolhaas. NAi Publishers, Rotterdam.

Cortés, J.A.

et al. (2006). AMOMA REM KOOLHAAS (I) Delirio y más. EL CROQUIS. Nº

131/132.

Cortés, J.A. et al. (2007). AMOMA REM KOOLHAAS (II) Teoría y práctica. EL CROQUIS. Nº 134/135.

Coyne, R. (2011). Derrida for Architects. Collection Thinkers for Architects. Routledge.

Dovey, K. & Dickson, S. (2002).

Architecture and Freedom ? Programmatic Innovation in

the Work of Koolhaas/OMA. Journal of Architectural

Education, 5-13.

EL CROQUIS. (1987-1998). OMA / Rem Koolhaas. 1987-1998. EL CROQUIS.

Nº 53+ 79.

Gargiani, R. (2008). Rem Koolhaas.

OMA. EPFL Press.

Heidegger, M. (2010). Caminos del bosque. Traducción al español de (Helena Cortés & Arturo Leyte trans.). Alianza Editorial. (originally

published in 1995).

Heidingsfelder, M. & Tesch, M. (2009). REM KOOLHAAS, más que un

arquitecto. Arquia/ documental 8.

Jencks, C. (2006/2007). “The Iconic

Building is Here to Stay” Published in HUNCH. Rethinking Representation The Berlage Institute Report. No. 11. Winter

2006/2007, 46-61.

Koolhaas, R. & Mau, B. (1995). S, M, L, XL. The Monacelli Press.

Koolhaas, R. & McGetrick, B. (2004). Content. TASCHEN GmbH.

Koolhaas, R. & Yoshida, N. (2000). OMA@work.a+u Architecture and urbanism: May 2000 Special Issue. The Japan Architect Co.

Koolhaas, R. (1994). Delirious New York. A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. The Monacelli Press.

Koolhaas, R.

(1995). “Bigness of the Problem

of the Large”. Originally Published

in : Koolhaas, R. & Bruce, M. (1995). S, M, L, XL

The Monacelli Press.

Koolhaas, R. (1996). Conversations With Students. Architecture at Rice. Rice University School of Architecture, Houston. Princeton Architectural Press.

Koolhaas, R. (2006). Post-Occupancy. DOMUS d’autore.

Koolhaas, R. et al.

(1997). O.M.A. Programa d’acció.Quaderns monografies.

Collegi D’architectes de Catalunya.

Moneo, R. (2004). Inquietud teórica y estrategia proyectual en la obra de ocho arquitectos contemporáneos. ACTAR.

Olbrist, H.U. [Architecture Biennale] (2010). OMA Office for Metropolitan Architecture (NOW Interviews) [Video]. Youtube.

Pallasmaa, J. (2001). The Embodied

Image. Imagination and Imagery in Architecture. AD Primers. John Wiley & Sons

Ltd.

Pasajes. (1998). OMA Revista

: PASAJES. Arquitectura y crítica.

Nº 59.

Patteeuw, V. (2003). Considering

Rem Koolhaas and the Office for Metropolitan

Architecture. What is OMA. NAi

Publisher.

Schrijver, L. (2008). OMA as Tribute to OMU : Exploring Resonances in the Work of Koolhaas

and Ungers. The Journal of Architecture. 13(3),

235-261.

Schrijver, L. (2012). Imaging the Future or Constraining the Now ? Architectural Representation

from Crisis to Boom, and Back Again. Unpublished Article, Courtesy of

the Author.

Schrijver, L. (2013). “The Zeebrugge Ferry Terminal, OMA. Architecture and the crisis of the whole.” Published in: Avermaete,

T. (ed) & Massey, A. (eds).

(2013). Hotel Lobbies and lounges. Routledge,

217-226.

Somol, R. E. (1999). “Dummy

Text, of the Diagrammatic

Basis of Contemporary Architecture.” Introduction to the Book : EISENMAN, Peter.

Diagram Diaries. Universe. Rizzoli international

Publications.

Ungers, O. M. (1982). Morphologie. City Metaphors. Verlag der Buchandlung Walther König.

Van Berkel, B. & BOS, C. (2006/2007). “After Image”. Published in HUNCH. Rethinking Representation the Berlage Institute Report. No. 11. Winter 2006/2007, 38-45.

Venturi, R. (1996). Iconography and Electronics Upon a Generic Architecture. The MIT Press.

Whiting, S., & Koolaas, R. (1999). A Conversation between Rem Koolhaas and Sarah whiting. Assemblage, 40, 36-55.

Yaneva, A. (2009). Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture : An Ethnography of Design. 010 Publishers.

[1] “Method of conceptual identity

and its consistent inconsistency through the analysis of Dutch Embassy in

Berlin by Koolhaas & OMA”.

Publised in Shodhkosh: Besa, E. (2023).

An Approach to the Architectonical Method Through the Analysis of the Dutch

Embassy in Berlin by Koolhaas & OMA. ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and

Performing Arts, 4(1), 1-16. doi: 10.29121/shodhkosh.v4.i1.2023.372.

Both papers are translated from the content of two epigraphs of the

chapter about Koolhaas that belongs to the PhD thesis by the author: Besa

(2015). Arquitecto, obra y método. Análisis comparado de diferentes estrategias metodológicas singulares de la creación arquitectónica contemporánea. Tesis Doctoral, ETSAM UPM. OAI: http://oa.upm.es/38053/

Published as a book in Spanish: Besa

(2021). Arquitecto, obra y método: Kazuyo Sejima, Frank O.

Gehry, Álvaro Siza, Rem Koolhaas, Peter Zumthor. Diseño Editorial.

The index and the conclusion of the PhD thesis of the author are

published in English in: Besa

(2017). Architect, work, and method. IDA: Advanced Doctoral Research

in Architecture. p 1157-1179

https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/70078?locale-attribute=en

[2] “The

relation between Word and object is therefore “arbitrary” and the thing being

referred to (the house) is not so much an object as a concept. Saussure’s

radical position about language and reality can be summed up by his

proposition: Saussure provides a systematic way of studying language which does

not require that language appeal to a reality beyond itself.” Coyne (2011), 14)

“In so far as there is ever a deep structure, a

foundation, a more profound, enduring or more structured substrate to language,

human psychology or architecture, Derrida shows this to be in flux,

indeterminate and in fact no foundation at all.” Ibid.

P. 19.

“The centre relies on what

is supposed to be built around it. Alternatively, the centre

is always ‘foreign’. It is something brought in from outside, by definition without justification, to found something new

and different to what was there before. The concept of foundation seems to rely

on this instability to establish its status as a core. Meaning is similarly

caught in this indeterminate play.” Ibid. P. 24.

[3] ‘moral’, ‘morality’, are words that Koolhaas insistently refers to. “One of the beautiful things

about the architecture is of course, that no matter how pretentious or

unpretentious it is, it is always used. (…) I think is for me, for instance,

one of the last connections to morality.” Heidingsfelder

& Tesch (2009).

“(…) It appears impressive, it not beautiful, whether

the architect influences it or not. The amoral position of such a building, the

effect of the scale alone and its intimidating volume, is something that is

very disturbing to architects, who always think that only they can make the

uniform substance of a building beautiful.” Koolhaas

(1996), 15-18

Derrida describes architecture as the last fortress of

metaphysic: “For Derrida these tangible factors conspire to render

‘architecture as the last fortress of metaphysic’.” (The factors, that this

quote refers to, are related with the concept of dwelling, nostalgia of origin,

human service, harmony, and beauty. These statements by Derrida have a direct

relation with Koolhaas’ attempt to deny any trace of precedent morality in

architecture) Coyne (2011), 60

[4] The quote comes from the manifesto “Bigness or

the problem of the large”. Nevertheless, it could be said that these words are

completely related to the question of meaning to which this paper refers.

Because in the end, both the study of the wall and the manifesto on bigness,

come from the same interest in the subversion of traditional relations within

the realm of architecture.

[5] This is an approach to Zeebrugge terminal which

is shared but also, more extensively developed, in the work by Lara Schrijver (2013).

[6] Lara Schrijver also analyses the influence and

resonances in the work of OMU (Ungers) and OMA

(Koolhaas), showing other alternative interpretations to the ones that are

developed in this paper. Indeed, the study on the images of the book Morphologie, City Metaphors leads Lara to

associate them with the interest in the formal autonomy of architecture of both

Koolhaas and Ungers. At the same time, these matched

images lead Lara to associate Ungers’ ideas with the

contradictory oppositions in the work of Koolhaas. “Rather than extrapolate the political directly into

their architecture and give it a physical form, they explored the formal

autonomy of architecture while attempting to understand its cultural

ramifications in the meantime.” P.256. “The freedom implied in the ideas of the

contradictio in oppositorum

and the oxymoron, becomes a tool in which formally antithetical spaces are

driven to the extreme. The manner in Which the two

architects employ these concepts differ slightly: Where Ungers

uses the contradictio in oppositorum

on a primarily formal level (almost as a compositional technique) it becomes

more of a strategic condition for Koolhaas –the oxymoron allows him a freedom

of design by creating a framework rather than a specific formal ‘style’.” Schrijver (2008), 257

[7] Other thinkers have also tried to recover the importance of the image

trying to compensate the excessive strength of western logocentrism. “Regardless of the historically prevailing view of imageless and

essentially verbal thought, seminal theories of purely visual thinking, such as

those of Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Gorgy Kepes and Rudolf Arnheim, have decisively expanded the understanding of the

realm of thought and creativity. (…) It is especially regrettable that

prevailing general educational philosophies around the Western world have

grossly undervalued the role of imagery and imagination as well as the sensory

and embodied dimensions of human existence and thought.”

From the same

author, the following quote insists in the arguments of the previous paper

about the Embassy, as it argues a prevalence of the concept and idea over the

semantic and even the perceptual condition of architecture.

“This bias is

reflected in the fact that art and architectural education as well as thesis

works in these areas most often have to be validated

by ‘academic standards’, which rather categorically mean the usual empirical

and logocentrically theoretised

criteria, instead of being encountered and assessed through their inherent

criteria of sensory impact, artistic imagery and emotional content.” Pallasmaa (2001), 34-35

On the contrary, what other

philosophers detect in the genesis of western modernity is the prominence of

the visual representation itself. “Así

pues, si se interpreta el carácter

de imagen del mundo como la

representabilidad de lo ente,

no queda más remedio, para captar plenamente la esencia moderna de la representabilidad,

que rastrear a partir de

esa palabra y concepto tan desgastados

–“representar”- la fuerza originaria de su nombre: poner

ante sí y traer hacia sí. Gracias a esto, lo ente

llega a la estabilidad como objeto y sólo

así recibe el sello del ser. Que el mundo se convierta

en imagen es exactamente el mismo proceso

por el que el hombre se convierte en subjectum dentro

de lo ente.” Heidegger

(2010), 76

[8] Unlike Venturi’s statements, Somol not only identifies postmodern iconicity as a merely

superficial superposition, but rather, in the semiotic critic, he finds a

recovery of architecture as a sign and image, and even, the definitive

overcoming of modern positive figuration of space and abstract form. “While Rowe and company attempted to replace the

neutral, homogeneous conception of modernist space with the positive figuration

of form, the neo-avant-garde began to question the stability of form through

understanding it as a fictional construct, a sign. This semiotic critique would

register that form was not a purely visual-optical phenomenon, not “neutral”,

but constructed by linguistic and institutional relations.” Somol (1999), 14

[9] Lara Schrijver has developed a paper on the effects of the crisis on

Koolhaas’ architecture with an analysis of Renaissance Dubai Tower. Schrijver

(2012)

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2023. All Rights Reserved.