ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Theoretical Perspectives on Language Acquisition in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL): Bridging Content and Communication

Dr. Arun George 1, Dr. Jalson Jacob 2

1 Assistant

Professor, Department of English, Government College Kottayam, Kerala, India

2 Associate

Professor, Department of English, Government College Kottayam, Kerala

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The

convergence happening in Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and

the resultant acquisition of a language (L2) involves integration of several

Second Language Acquisition (SLA) and subject learning theories. The SLA

theories support this method of learning where L2 acquisition happens when

subject is learned through interaction. This paper points out some of the

theoretical underpinnings behind a successful and practical L2 acquisition

happening in CLIL. |

|||

|

DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i2.2022.1751 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL),

Content Based Instruction (CBI), Direct Method, Audio-Lingual Method, Output

Hypothesis, Zone of Proximal Development, Scaffolded Learning |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Learning a language has historically been intertwined with power dynamics, cultural exchange, and practical needs. In ancient times, conquerors often learned the languages of the people they subjugated to better understand their culture, access local knowledge, and facilitate governance and trade. This practice allowed the victorious to use the language of the vanquished as a strategic tool for various purposes, ranging from administration to cultural assimilation.

This historical context also mirrors modern-day challenges in learning content through a language that is both unfamiliar and complex. When students face the dual challenges of mastering new subject matter in an unfamiliar language, it requires significant effort and resources to achieve their learning objectives. This struggle is common in regions where educational content is delivered in a language that is not the mother tongue of the student. It underscores the importance of language proficiency in facilitating effective learning and understanding across different subjects.

The cognitive, socio-cultural, and constructivist theories that emerged in the twentieth century significantly influenced the development of various methodologies in learning. These theories, emphasizing the mental processes, social interactions, and active construction of knowledge, paved the way for diverse approaches to education. Language content, as a crucial element, became a focal point in many of these experimental methodologies, as it is integral to communication, understanding, and knowledge acquisition across cultures and contexts.

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) emerged in Europe as "a dual-focused educational approach" (Coyle et al. 1), designed to integrate both content and language learning. The approach was notable for its efficiency, as it was implemented "without requiring extra time in the curriculum," according to the Commission of the European Communities (8). CLIL was introduced as a response to the generally poor outcomes of traditional language teaching, positioning content as a powerful and effective resource for enhancing language acquisition. This approach not only improved language proficiency but also enriched students' understanding of various subjects through the medium of a foreign language.

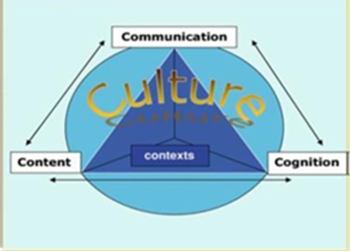

The four Cs framework (Coyle 1999) encapsulates the integrated aspects of CLIL, emphasizing content, cognition, communication, and culture. Coyle argues that classroom learning occurs through the progression of knowledge, skills, and understanding of content, facilitated by cognitive processing, communicative interaction, and cultural awareness (1999: 60). Coyle et al. also highlight the need for learners to receive instruction and experience real-life situations to acquire language naturally (Coyle et al. 11).

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 The

4Cs Framework for CLIL (Coyle) |

CLIL leverages active discourse, often missing in traditional subject content pedagogy, to enhance language learning. Content serves as an "authenticity of purpose" (Coyle et al. 5), offering a rich and previously underutilized resource for language acquisition. When academic content is used as the foundation for language learning, acquiring the language becomes a natural and essential part of the educational process. Content Based Instruction (CBI) focuses on teaching language through content that can be handled by the language teacher, such as peripheral topics or general essays. Immersion programs, in contrast, use a second language (L2) to teach academic content without specifically addressing language aspects, as this is managed by content teachers. In Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), however, time is dedicated to developing all four language skills while simultaneously learning subject content, making language acquisition a natural outcome of the learning process.

In CLIL, learning occurs in three distinct contexts: contextualised CLIL within the classroom, where procedures are tailored to the learning environment; contextualised language in the content domain, where language acquisition occurs; and content learning within a Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) context, focused on subject-specific skills. The effectiveness of CLIL relies on identifying and differentiating language and content variables according to learners' levels and needs. Meaningful learning is achieved when the CLIL teacher prepares materials that align with both the learner's background and the learning context. This flexibility allows for the development of customized strategies. This approach highlights the adaptability of CLIL, as the same content can be taught differently in various institutions based on specific factors, a consideration often overlooked in traditional learning processes.

Language elements encompass any additional language a learner may use, which could be a foreign language, a second language, or a form of heritage or community language (Coyle et al. 1) in CLIL. The practitioners distinguish between content language and general language for empirical purposes rather than contrasting them. To understand these differences, the terms Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) and Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS) are useful (Cummins 198-201). In CLIL, vocabulary is acquired through the learning process and contextual application, integrating both the subject-specific and general English vocabulary relevant to certain subjects. According to Prof. David Marsh in a 2007 interview, constructivist methodologies and scaffolding address the issue of inadequate language affecting content learning in CLIL. Butzkamm suggests that CLIL shifts the focus of language from being medium-oriented to message-oriented (168). The goal of CLIL is to achieve functional competence in the language rather than native-like proficiency (Pérez-Cañado 318). Nevertheless, learners often reach a high level of proficiency within a few years of exposure to CLIL.

Beardsmore and Baetens describe the challenge in language classrooms as follows: "Language lessons are vital for accuracy, but do not provide sufficient contact time with a target language and need supplementing with opportunities to use language in meaningful activities" (12). This issue is prevalent in the L2 learning scenario in polytechnics, where such opportunities are often lacking. To address this, incorporating interactive and active learning methods in classrooms can enhance language production skills. Transforming classrooms to support active learning through interaction can improve L2 production. Language teachers should foster the use of language that develops Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS), which is crucial for building Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP).

Dalton-Puffer characterizes CLIL as an “educational model for contexts where the classroom provides the only site for learners’ interaction in the target language” (2011: 182). It represents an “innovative fusion” of content and language, achieved through a “balance between individual and social learning environments” (Coyle et al. 1, 3). Content serves as a valuable tool to enrich the language learning environment, effectively integrating both language and content pedagogy. As students learn content, they simultaneously acquire language, with interactive content learning promoting the subconscious skill of language acquisition.

2. Content and Language Learning Theories and Methods Integrated in CLIL

There is a robust theoretical foundation supporting the integration of language and content learning. Mohan highlights the evolving aspects of education and L2 learning in a multilingual and multicultural world, including “language as a medium of learning, the coordination of language learning and content learning, language socialization as the learning of language and culture, and discourse in the context of social practice” (2002:303). This integration is explored through content and language-based teaching methods, merging the positive elements of both Second Language Acquisition (SLA) theories and general education or content learning theories.

The Input Hypothesis theory of Krashen underscores the importance of rich input in CLIL. The fundamental learning process in CLIL involves interaction in pairs and groups, supported by Social Constructivism (Vygotsky), contextual learning and Interaction Hypothesis (Long). CLIL classrooms reinforce procedural knowledge and utilize techniques from Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), which supports communication as the main purpose of language. While both CLT and CLIL are holistic approaches, CLIL offers a higher level of authenticity in its purpose (Coyle et al. 5). Communicative language approaches emphasize meaning in language learning, and the "focus on form" (FonF) approach, introduced by Michel Long, integrates attention to language aspects within a communicative framework, which is implemented in CLIL (Doughty and Williams 3). CLIL assimilates oral interaction techniques from the Direct Method and Audio-lingual Method, with content providing meaningful input alongside language elements. The Output Hypothesis of Swain connects with CLIL’s language acquisition process, highlighting the trial-and-error method for testing productive skills.

3. CLIL and Socio-Psychological Theories in Learning

Prof. Marsh, in a 2007 interview, noted that CLIL connects learners to their own “worlds” through multi-mode technology and emphasizes the impact on the brain when language learning becomes “acquisitional and not just ‘intentional.’” Coyle et al. explain that various fields and theories contribute to education: cognitive neurosciences, the works of Bruner, Piaget, and Vygotsky in socio-cultural and constructivist contexts, along with multiple intelligences (Gardner, 1983), and language learning strategies (Oxford, 1990). These theories collectively enhance curricular relevance, motivation, and learner involvement (Coyle et al. 3). Halliday describes language development as a “sociological event” (139). Vygotsky links learning and cognition with social interaction, culture, and the zone of proximal development (ZPD) (84-91). CLIL’s learner-centred, cognitive, and constructivist features reinforce both content and language learning.

The terms convergence and synergy are central to understanding CLIL methodology, reflecting its integration of language and content learning. Traditionally, language learning and academic content were taught separately, but since the 1950s, experiments have demonstrated the benefits of integrating these areas. This convergence and synergy address many shortcomings of traditional education systems. As education evolved from a traditional to a learner-centred approach, methods like CLIL gained prominence. Marsh et al. highlight that a key feature of CLIL is “the synergy resulting from communication orientation on the language, the content, and the interaction as it takes place within the classroom” (51). In a CLIL classroom, learning theories and second language acquisition theories merge, creating an environment where language and content aspects are intertwined. This integration generates a dynamic learning process where distinguishing between language acquisition and content learning becomes challenging. The mutual support provided by content and language in CLIL demonstrates their inextricable relationship. Coyle et al. affirm that CLIL represents an amalgamation of language and subject learning, reflecting the convergence of previously fragmented curriculum elements (Coyle et al. 4).

4. Learner-Centred Activities and Interaction

Communication plays a crucial role in CLIL, aligning with modern learning theories focused on learner-centred approaches. Language development in CLIL occurs through dialogue, and effective talk for learning is central to the methodology (Mercer 102). In CLIL, the learner, as the primary stakeholder, should be actively involved in the learning process, with learner-learner interaction proving particularly beneficial. Teacher talk, often one-way, has a more restricted role compared to the importance given to learners actively using and inventing their language. Providing ample time for communication enhances both content knowledge and language acquisition. Vygotsky and Bakhtin argue that language, thinking, and culture are constructed through interaction, which is fundamental to learning (Vygotsky 84-90; Bakhtin 81). Brown et al. emphasize cognitive apprenticeship developed through collaborative social interaction (40). Hanneda and Wells identify three aspects crucial for student dialogic talk in CLIL: comprehensible input (Krashen), comprehensible output (Swain, 2005), and the production of appropriate social and communicative strategies (118-119).

In CLIL, developing listening, speaking, reading, and writing (LSRW) skills simultaneously is emphasized, though in practice, this balance is often not achieved, as highlighted by stakeholder responses. Specifically, the productive skill of speaking is frequently underdeveloped due to a lack of opportunities for its use in the learning process, leading to an imbalance in language skill acquisition. CLIL addresses this issue by providing ample opportunities for learners to enhance their speaking abilities. The design of CLIL focuses on meaningful interaction, student-centred learning, ample input, and purposeful learning, effectively utilizing the full scope of language learning in the classroom and fostering communication skills.

Active discourse and interaction are integral to CLIL, reflecting its learner-centred approach. In CLIL classrooms, learners engage in "the peer group powers of perception, communication, and reasoning" (Coyle et al. 6), exemplifying the power of dialogic teaching (Alexander, 2008). The core idea is that meaning is constructed through participatory learning, with constructivist and participatory principles central to CLIL as noted by Dalton-Puffer. Cummins emphasizes the importance of "the centrality of student experience and the importance of encouraging active student learning rather than passive reception of knowledge" (108). CLIL also incorporates scaffolded learning, where support is provided by more 'expert' individuals or resources (Coyle et al. 29), aligning with the learner-centred approach.

Rich input, authentic interaction, and mediated learning are key methodologies in CLIL classrooms. Research underscores the significance of discourse as a tool in learning (Alexander 108), and the success of dialogue-centred approaches in socio-cultural theories is further explained by Haneda and Wells (114-136).

5. Conclusion

CLIL offers a natural method of L2 learning that is akin to L1 acquisition. This also helps even average learners in L2 acquisition. The SLA theoretical framework supports and validates the effectiveness of language learning in formal classroom settings. The educational theories, socio-psychological theories and actual interactive learning in CLIL reinforce the scope of L2 acquisition in classrooms. Subject content learning and L2 acquisition are mutually supportive also that makes CLIL more meaningful.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Gardner, H.

(1983). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Book Company.

Krashen, Stephen. D. (1985). The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. Longman : New York, USA.

Mercer, Neil.

(2000). Words and Minds: How We Use Language to Think Together. Routledge.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society. Harvard UP.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2022. All Rights Reserved.