ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Reading Resemblances and Fluidity between the Zikir songs of Azan Fakir and Other Song Genres in Assam

1 PhD Research Scholar, Department of Theatre and Performance Studies, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Zikir songs of Assam are the Assamese Islamic devotional songs composed by the Sufi figure Shah Miran, alias, Azan Peer Fakir, who came to Assam from Baghdad in 17th century. Assamese scholars categorize zikir under the folk Bhakti or Sufi genre. According to Syed Abdul Malik, a pioneer writer on the subject, the word zikir is said to have been derived from the Arabic term ziqr, which means to remember, listen to and to mention the name of Allah. Interestingly, the concept of remembrance of the Divine, like in zikir, also resonates with the Neo-Vaisnavite Bhakti philosophy of Sankardeva and Madhavdeva of 15th century Assam. There exist philosophical and lyrical resemblances not only between zikir and borgeet (Vaisnavite prayer songs), but also between zikir songs and lokageet, and dehbichar geet. Musically, there are resemblances of rhythmic patterns and melodic phrases, which reflect a fluid exchange amongst zikir and other folk genres. This essay is

a musicological exploration and lyrical study of some examples showing these

philosophical resonances and musical fluidities. In doing so, the article

highlights the synthesis of the merging of the Hindu and Islamic

philosophies, lyrical and musical aesthetics, in and through the songs of zikir by Azan Fakir. |

|||

|

Received 10 June 2022 Accepted 01 August 2022 Published 10 August 2022 Corresponding Author Dipanjali Deka, dipanjali.cp2@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i2.2022.155 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Zikir, Bhakti Movement,

Assamese Sufism, Musical Fluidity, Folk Music |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

I carry no discrimination in my mind O Allah,

I do not see a Hindu different from a Muslim, O Allah!

When dead, a Hindu is cremated

While a Muslim buried under the same earth

You leave this home

To reach that Home

Where all merge into one!

-Azan Fakir

The above is a zikir

(translated from Assamese), which is an Islamic Assamese devotional song-poem,

composed by the 17th century Sufi figure named Shah Miran or Azan Peer Fakir. Azan Peer Fakir is said to have

migrated from Baghdad to Assam via Ajmer and Delhi. On reaching Assam with his

mission of spreading the tenets of Islam, he was surprised to find that the

Muslims were following Islam only in the name. They were merged in the larger

Assamese Hindu mannerisms of social and religious life, which was mostly Neo-Vaisnavite in nature following the Nama-Dharma of Vaisnavite Gurus Srimanta Sankardeva and Srimanta Madhavdeva. Shah Miran is said to

have learnt the Assamese language himself, married a local woman, and merged

into the Assamese lifestyle. He imbibed musically and philosophically with many

existing rhythms, folk melodies, and religious philosophies. It became possible

for him to propagate the Islamic values through this merge with the existing

aesthetic and philosophical values of the folk Assamese life.

Today, multiple levels of synthesis exist amongst zikir and other song genres of Assam. I attribute this

synthesis to the fluid nature of loka parampara or folk traditions working in tandem with the

accommodative and inclusive philosophy of Bhakti or Sufi expressive cultures.

2. PHILOSOPHICAL RESEMBLANCES

In 15th century Assam, two figures, Sankardeva (1449-1569 AD) and Madhavdeva (1489-1596 AD) brought in

a literary and cultural renaissance in Assam through their brand of Vaisnavism that propagated the philosophy of Eka Sarana Nama Dharma, meaning the

single-minded devotion of Vishnu or Krishna. The music forms of borgeet and namakirtan are vocal

music genres originating from this brand of Neo-Vaisnavism.

All the eminent scholars who have written on Azan Fakir and his music,

including Syed Malik (2003),

Hossain (2014),

Deka (2012)

and so on, have paid attention to the influences of the Sankari

arts and philosophy on the music of Azan Fakir.

Nama-Dharma of Sankardeva

preached the remembrance of the Divine Name of God through various modes of

Bhakti: sravana

(listening to the recital of the Name and glories of Hari or Vishnu), kirtana (recital

of the glories and Name of Hari), smarana (recalling or remembrance of the Lord’s Form and

Name) and so on.

Two Vaisnavite songs

reflecting the kind of sacred significance of Nama in Vaisnavite

faith can be Hari Nama rase Vaikuntha

prakase and Naame

Gangaajol loboloi komol boi aase hridayar

maaje. While the first song says that Hari’s Name is the divine ambrosia that

would open the doors of Vaikuntha

heaven, the second song reflects that the sweet nectar of Nama is the pure Ganga flowing

through the devotee’s heart.

One finds resonance of a similar importance given to

the chanting of the Name even in Azan Fakir, who followed the Sufi philosophy

of zikr, meaning remembrance. In Jibar Saarothi Naam O Allah,

the devotee calls the Holy Name of Allah as the only true companion to life. Kevol Naame Kevol Naam, kevol Naame rati, dine rati loba Naam nokoriba khyoti gives an

urgent message to waste no time and surrender oneself to the chanting of the

divine Name, day, and night. In yet another zikir, Momin bhai dosti rakha Allahe param dhan the poet addresses

the bhakta (devotee) companion that

the Name is in fact the ultimate treasure leading to Divinity.

Among other things, many Vaisnavite

songs also talk of the transience of materialistic pleasures and worldly

sufferings of maya. One may take the Borgeet Pawe pari Hari koruhu katori in which the

bhakta surrenders on the feet of Rama, beseeching for the rescue of the soul

from the poisons of the material distractions (bisaya bisadhara bise jara

jara Jivana narahe thoro). A very similar critique of worldly pleasures

and illusory attachments is heard in the Zikir, bisoy khon gologroho bisoykhon bisoy golore mani,

where Azan Fakir rebukes material pleasures as the ominous presence (gologroho)

dangling from the neck Deka (2012) 27-28. The song cautions the devotee to see the reality

that because of this ominous presence she remains dry even within water. This

metaphor of dryness within water is suggestive of the failure to access the

Divine even while being near the Divine, because one

is constantly blinded by the illusory attachments.

However, it is not just Vaisnavite music that zikir is

seen to have resonances with. The other folk music genres of Assam like Kamrupi lokageet, Goalpariya dehbichar geet and tokari geet also find resonances in zikir

in some or the other way. The

Goalpariya lokageet are

songs with the themes of dehtattva and dehbichar that speak of the impermanence of this human

body, the futility of all material wealth, decay, and death.

There is a striking

resemblance of imagery between the zikir, lorali kaal gol haahote khelate bhakti kora kun kaale

and the Goalpariya geet

sung in Western Assam Balyo kale gelo haashite khelite

Joubono kaalo gelo ronge. Goalpara has proximity to Bengal, hence Goalpariya Lokageet in its content and tonality are very similar to

the Baul songs of Bengal. In both the

abovementioned songs, the zikir and the Goalpariya lokageet, there is reflection on the merriment, pleasure-seeking,

and laziness with which one passes youth and childhood, failing to recognize

the time one wastes away from seeking God.

It is evident that there is a close affinity amongst

these songs at the level of philosophical ideas and images as well as language

and metaphors. However, it is also important to understand that there is

not just a conversation (or resemblance) between Azan Fakir and other existing

traditions of Assam but also between Azan Fakir and other Bhakti and Sufi

happenings all around the subcontinent. It is important to place it within the

folk culture of Assam, but it would be a blunder to not look at it under the

larger umbrella of Bhakti as well. In

one bhajan of Kabir, to describe the ignorance of a devotee who searches

for the Truth in the wrong place, he uses the metaphor, paani

me meen pyaasi (Like

the fish who stays thirsty in water). Interestingly, there is a zikir wherein appears a markedly similar metaphor, agni more jaarot pani more piyaahot (the fire

dies of cold and the water of thirst). Clearly the spiritual vocabularies of

disparate regions have much more commonness than one may instantly give credit

for. Hence, one can say that Azan Fakir’s zikir does

not just reflect resonances between the regional bhakti folk philosophies, but

he also stands at the intersection of a larger thread of bhakti philosophy

cutting across different regions of the subcontinent.

3. Melodic Exchanges and Fluidities

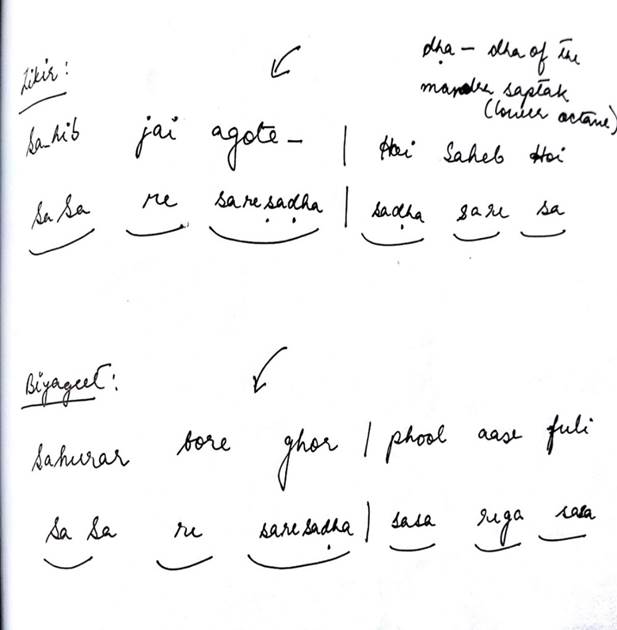

To understand the musical fluidity between zikir and other song genres of Assam, I interviewed Anil Saikia,

a renowned folklorist of Assam. Saikia promptly

pointed towards the tune of a biya geet (wedding song) sahurar bore ghor phool aase fuli (Flowers bloom in my in-laws’ house) (personal

communication, Guwahati, June 12, 2018).

He demonstrated to me by singing the musical similarity of the biya geet with the zikir, saahebjaai aagote hoi saheb hoi (Our Guru-Saheb leads us,

Hail O Hail). Both the songs are sung in the kaharwa style

(8-beat) rhythm in the same medium laya (tempo). The musical notation below should give the

readers a little idea of the melodic similarity.

With written notation, one may not be able to fully

articulate the intricate musical particularities. As Barthold Kuijken’s

self-explanatory book-title goes, Kuijken (2013)The Notation is Not the Music (2013). One has to only musically imagine the embellishments in between

the notations. There is a kaaj (musical

embellishment) that is rendered by the singer in the quick succession of the

small melodic phrase sasaresaresadha in the beginning of both the above

songs. This melodic phrase can be sung in numerous ways by a singer with a

permutation and combination of numerous rhythms and tempos. However, it is one

particularly playful and swift motion of swaras (notes) as is done in the

Assamese folk music context, that makes it recognizable. This common way of

performing the musical embellishment is what connects the wedding song and the zikir musically.

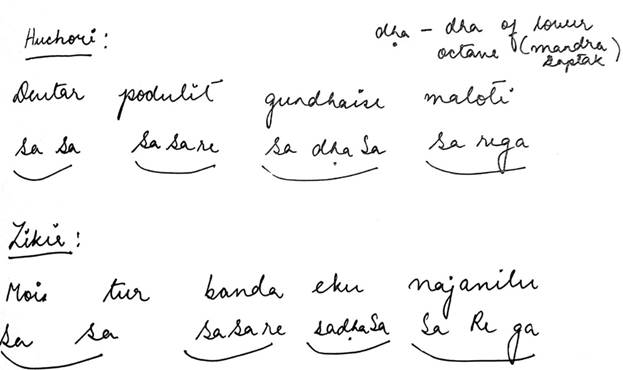

In yet

another example, we can see a striking musical resemblance between a huchori and a zikir. A huchori is a form

of choral singing heard during Rongali Bihu, a

spring-season festival of the Assamese. There is one huchori,

deutar podulit gundhaise maloti keteki mole molai, O gobindai ram (My

father’s frontyard is full of the fragrance of maloti and keteki O Gobindai

Rama) (Maloti

and keteki

being two fragrant flowers found widely in Assam). Now the melodic patterns of this huchori are strikingly similar to

that in the zikir, moi tur banda eku najanilu, Allah hey (I am your ignorant servant who

knows nothing O Allah),

While

one is a folk bihu song celebrating springtime

fertility the other song is a call to the Divine from a devotee. One is

reflective of the laukik

(worldly) affairs while the other sings of the alaukik (other-worldly,

spiritual) relation. However, despite the distinctiveness in the lyrical

content of the two, there is an unmistakable musical resemblance through a

common melodic phrase sasasasaresadhasasarega

sung with a similar kaaj (embellishment) in the movement from

one note to another.

Ismail Hossain, an eminent scholar who has worked

extensively on Azan Fakir and Zikir, speculates that

Azan Fakir with his creative genius composed his songs in accordance with the

music of the places he was settled in at each point of time (personal

communication, Guwahati, April 21, 2018).

This can be an interesting perspective towards understanding the

intra-cultural (intra-musical) exchange that might have happened (or still

happens) between zikir and other songs genres at each

point in the journey. However, more than attributing this to the creative

genius of Azan Fakir alone, I would also accredit the common folk in every

generation that shaped zikir into a song of their

own, linguistically, and stylistically. Because of this traditional oral

fluidity, today in practice one can see ample resemblances and similarities in

the musical characteristics of zikir and many other

Assamese folk forms.

4. Bilateral Exchange of Islamic and Hindu Vocabulary

In one of Madhavdeva’s Borgeet, the dhruvansha

(refrain) says:

Bhoyo

bhai saabodhaan

Jaawe

naahi chute praan |

Gobindero

faraman

Nikote

milobo jaan||

Mahanta (2014)157

O brother, beware!

Your soul is leaving.

It is Govinda’s order,

Meditate on this moment of life.

This borgeet is said to have

been sung by Madhavdeva when Sankardeva’s

son-in-law Hari was about to be beheaded under the orders of the erstwhile Ahom

King (p.158). In that hour of death, till the soul leaves Hari should meditate

on every passing moment of this transient life; that Madhavdeva

says is Govinda’s faraman

(order).

The word faraman however, is not a word from the

erstwhile or current Assamese Hindu vocabulary and is clearly an import from

the Islamic vocabulary. This hints at a fluid unrestrained flow of language

from one side to another, beyond the religious affiliations of the communities

singing the songs.

Again, during my conversation with Ismail Hossain, he

narrated his encounter with a Kamrupi biyanaam (wedding

song) that was being sung by some Brahmin women in the district of Nalbari in Assam.

Arobore

mokka, arobore mokka

doraghoror

namoti misa kothar pakka

The

Arabic mecca, the Arabic mecca,

The

folks from groom side, in lying aren’t they pakka (experts)?

On asked

about the reference of mecca, the women replied that they haven’t seen the mecca,

but they knew it was a sacred site for Muslims. On further probed as to their

motive behind using it, their answer was rather simple. “The groom side women

were teasing us and while retorting back we needed to have a word which would

rhyme with pakka, hence came mecca!” Hossain reflects

on this incident and asks me, “What secularism, isn’t it?” What Hossain was

trying to point at was the cultural syncretism that was reflected in the fluid

borrowing of Islamic vocabulary by the Hindu singing women.

5. Conclusion: Fluidity of the Folk and Bhakti - Sufi Expressions

The

concept behind the word “folk” was born in Euro-America more than two hundred

years ago. In the United States, “folk music” combines a sense of

old songs and tunes with an imaginary “simpler” lifestyle, featuring the

mountaineers of Appalachia and the African American blues singers, all playing

acoustic instruments—guitar, fiddle, banjo—with a hint of social significance.

In Europe, even though the word comes from the German volk (folk), the

genre has different overtones based on local social resonance Slobin (2011) 1. Outside the Western world, “folk” exists as a term

from foreign shores. In India, it bears colonial traces and class markings, as folklorica does in Latin American usage

(p.2).

Folk culture as understood in commonsensical terms is

an “expressive culture” (p. 6)

of the many ways that

people perform feelings and beliefs. Folk culture is what emanates

from the lives of the common people, and like a river, changing shapes,

“routes” and colors from one region to another. Even within one region, there

are numerous styles to one particular ‘folk’ form, due

to the factors of continuous influences from music of neighboring regions,

influences from other genres within the same region, collaborations amongst

different artists and usage of different instruments with changing times,

individual artistic dispositions and so on, which are constantly at work. That

the folk forms or genres are mostly the ones which are circulated in an oral

mode make them suitable for fluidity and change.

The nearest parallel term which defines the ‘folk’ in

the Indian scenario is perhaps Loka, as used in loka parampara,

i.e., people’s traditions or the local traditions. Here we are largely looking

at the umbrella containing local, regional, oral, and vernacular traditions. In

the context of music of Assam, one may say, ‘lokasangeet’

or ‘lokageet,’ literally meaning ‘people’s music’, is

a parallel for folk music.

The Bhakti and Sufi oral traditions of the Indian

Subcontinent are part of this long-standing folk tradition or loka parampara. The Indian Bhakti

movement came into being around seventh century AD in Tamil Nadu and gradually

took hold in the other regions of the subcontinent reaching its expressive

zenith in the medieval period. Music and poetry have been the

predominant modes of expression in this movement. Bhakti, very broadly, has

been a movement which facilitated the personal form of devotion of the devotee,

thus breaking the hegemony of the Brahmin priesthood. Bhakti is not a

monolithic phenomenon as it varies according to different socio-political and

cultural contexts. The musical expression also differs in different contexts,

depending on its employment of local languages, metres, and rhythms. Naturally,

it meant a huge uprising of the vernacular mode of expression, where the

devotees communicated with the Divine in the most day-to-day language, as, in Arundhathi Subramanium’s words,

the vernacular came closest to the “many shifts of the bhakta’s inner weather”

(Subramanium, 2014, xiii)

Hence,

in most cases, the secular folk and the devotional Bhakti expressions have

merged conveniently, in linguistic and musical styles. For both,

travelling spontaneously with time, there is no way to ascertain any one ‘authentic’ sound. Bhakti and Sufi poets have been

travelers from one place to another, reciting and singing their poems in

different regions with distinct musical styles. Each region treats the poems in

their own unique vernacular style. Folk forms in general are by nature fluid

entities, reflecting beliefs of the people, by the people and for the people at

any given time. In the understanding of folk expressive cultures, James Clifford advises us to think

of “routes” rather than “roots.” Slobin (2011) 7. Hence one

gains more by looking at bhakti and the folk expressions, through “routes”

rather than “roots,” in order to understand them as

fluid, malleable and open expressive cultures subject to influence,

assimilation and transformation.

Jin-Ah Kim, in his study of

Cross-Cultural Study of Music regards cross-cultural music as a “distinct,

dynamic-complex process, determined by the configuration of evolving relations

between different systems of reference” Kim (2017) 29. These systems of reference -

ethnic, social, national, regional, institutional, medial, and specific to

groups or persons - do not exist in isolation, but develop in mutual,

ever-changing relations to each other. The actors involved continuously

renegotiate these relations.

I invoke

Jin Ah Kim’s way of looking at cross-cultural music

making in my studying any culture, or cultures, as existing within/along with

other cultures. This allows me to look at the characteristics of any expressive

form, music or not, as fluid objects changing shape with time and other

external influences from surrounding cultures. Standing amidst various genres

of music within a region, I am able to see the samenesses and resemblances amongst them, as a

fluid and continuous exchange under various circumstances.

Applying these frameworks, one can argue that the philosophical, lyrical, and musical exchanges, resemblances, and fluidities that we observe in zikir (with an Islamic Quranic origin) vis-à-vis other song genres of Assam (with a non-Islamic origin), are a part of a constantly evolving cultural performance. These exchanges come through a socially imitative behavior wherein we see a close musical imitation amongst styles within geographical proximity in a region. This hints at the larger notion of a socially cohesive behavior through music. The resemblances of musical embellishments amongst different song genres reflect the sense of belonging to one region, or one larger common musical culture. Like James Clifford, I too would not use the word ‘root’ for folk Bhakti and Sufi oral traditions but would go for ‘routes. Different Bhakti-Sufi folk genres may have roots in various religious or ethnic sources, but their ‘routes intertwine, intersect, share, connect and communicate-socially, philosophically, ideologically, musically; and hence show resemblances and sameness at multiple levels.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the reviewers for their comments. I am grateful to my supervisor Prof. Partho Datta for his support.

REFERENCES

Deka, B. (2012). Asamiya Zikir Aru Zari Gitar Rohghora. Minati Kalita.

Hossain, I. (2014). Azan Peer Aru Zikir Zarir Mulyayan. Jyoti Prakashan.

Hossain, I. (2015). Asomor Musalmanor Oitijya Aaru Sanskriti. Banalata.

Hossain, I. (2015). Edited. Azan Peer Aru Zikir. Chandra Prakashan.

Kim, J. (2017). Cross-Cultural Music Making : Concepts, Conditions and Perspectives. International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, 48(1), 19-32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44259473.

Kuijken, B. (2013). The Notation is Not the Music : Reflections on Early Music Practice and Performance. Indiana University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt16gz82s.

Mahanta, B. (2014). Borgeet. Student Stores.

Malik, S. A. (2003). Azan Peer Aaru Xuriya Zikir. Students Stores.

Slobin, M. (2011). Folk Music A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Subramanium, A. (2014). Eating God : A Book of Bhakti Poetry. Penguin Ananda.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2022. All Rights Reserved.