ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

THE MODALITY OF PROPPIAN “FALSE HERO”: NEITHER A HERO NOR A VILLAIN IN (FOLK) NARRATIVES AND REAL LIFE

1 Assistant Professor of Folklore, Department of Tribal Studies, Central University of Jharkhand, Cheri-Manatu, Ranchi – 835222, Jharkhand, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Being the

contemporary of Roland Barthes and also prominent

scholar in French Semiotics, and also known for founding the Parisian School

of Semiotics, Algirdas Julien Greimas, with his

formal trainings in structural linguistics shaped the theory of signification

by adding plastic semiotics. Indeed, his masterly contributions that had

given a new direction in the study of narratives include the famous semiotics

square, actantial model, concepts of isotopy,

narrative programme and

the semiotics of the natural world. However, the actantial

model developed by Greimas in 1966 provided an

analytical tool for studying various actions carried out by different actors

(“actants”) in a real or fictional story. Although developed from the

suggestion given by Vladimir Propp that his [Propp’s] seven dramatis personae

such as ‘villain’, ‘donor’, ‘helper’, ‘princess/sought-for-person’,

‘dispatcher’, ‘hero’, and ‘false hero’ could be reduced further, Greimas proposed the actantial

narrative schema with six actants that manifest their movements of

relationship along the line founded on knowledge and power. However, the

‘false hero’ as one of the dramatis personae could be seen as important as,

and as similar to, others in the narrative

structure, its modality is quite interesting, and it tends to warrant an

academic discussion to contemplate its morphology. Taking few examples from

folktales and drawing insights from the Greimasian actantial model, this study presents the semiotic account

of the ‘false hero’ to highlight the fact that the ‘false hero’ occupies a

significant place not only within the real and fictional stories but also in

daily life, by explaining the veridictory modality

structure of truth and falseness. By drawing examples from folktales, this

article comprehends the nature of the ‘false hero’, who is neither a hero nor

a villain, for providing a grammatical framework that facilitates our smooth

handling of the notion that is indispensably occupying our everyday life. Therefore,

the significance of this paper is that it is lessening our efforts to

decipher the nature of different characters in different forms of narratives

and their presentations in different media. |

|||

|

Received 01 June 2022 Accepted 20 July 2022 Published 26 July 2022 Corresponding Author M.

Ramakrishnan, ilakkiyameen@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i2.2022.150 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Narratemes, Morphology, Actants, Modality, Aspectuality, Actantiality |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

This

article that deals with the ‘false hero’ has a larger goal in delineating an

“unusual” subject rather than the “unwanted” one either in folk narratives or

in our daily life, and while doing so it explores the nature and purpose of

universality of human expressions and their cultural variations. Interestingly,

the activity and modality of ‘false hero’ is an integral part of Vladimir

Propp’s thirty-one functions, “24 (L) Unfounded claims” – “A false hero

presents unfounded claims” and “28 (Ex) Exposure - The false hero or villain is

exposed” it is submerged and becomes an integral part of the actantial model of

A.J. Greimas, and it has an overwhelming presence in the socio-cultural and

political life of individuals. Thus, this article constantly refers to insights

given by both Propp and Greimas in the process of establishing the morphology

of ‘false hero’ on the one hand and its socio-linguistic relevance on the other

hand. The abstracts of some of the folktales/stories are given as point of

reference as well as the point of departure in handling the concept of the

false hero. The reason for choosing the ‘false hero’ cannot be a matter of

convenience, rather it’s ontology reflects it as a stereotypical or stock

character within the folktale genre whose intervention cannot be treated as

insignificant. Their frequent occurrences in folktales and similar expressions

in daily life could possibly make these characters appear more as simplified

archetypal characters. Although it was proposed as one of the seven dramatis personae by Propp after

carefully going through the Russian folktales, it appears almost across

cultures and societies, and thus it has become an indicator of universal nature

of human creativity with cultural variation. Thus, this article gains significance

for the reason that its contemporaries the Proppian

and Greimasean approach to narrative structure in

understanding the nature and role of the “false hero.”

2. Occurrences of False Hero –

Examples

Those who

are not familiar the narrative elements in a folktale, here are few examples

that will convince them that the occurrence of false here is quite a common

phenomenon in folktale genre across the world with variations in appearance and

deeds:

1)

Summary of “The Two Brothers”: There was a King whose two sons left the palace in

search of their fortune when faced ill-treatment by their stepmothers. The

elder brother reached a nearby town where the King died recently and the sacred

elephant which was entrusted to find a suitable person for the vacant throne

chose the elder brother. A king of another town had announced a reward, half of

the kingdom and his daughter in a marriage, for killing the problem creating

ogre. The younger brother killed the ogre in a fierce fight, and as he was

tired went to a deep sleep. A scavenger lifted the prince and put him gently

into a clay-pit close by and covered him up with clay and took the ogre’s head

to receive the reward from the King. Since the King was suspicious of the

scavenger, he gave him a half of the kingdom, but delayed the marriage. The prince

was rescued by some potters and realized the development. But the

scavenger-King came to know about the prince and made many attempts to

eliminate him. But the Prince escaped from all the attempts and reached the

country ruled by his brother and where he married the Prime Minister’s

daughter. With his brother’s help the scavenger-King was punished and the

kingdom was given to the elder brother who married the King’s daughter Steel (1894)129-143.

2)

Summary of “Prince Half-a-Son”: There was a King who had no children. With the advice of

a faqîr all the seven queens got a son each.

But the last queen’s son was half-a-son as her pthe

mango she ate to bore the child was already half eaten by a rat. The six

brothers attempted tricks to eliminate the half-a-son, but he managed to escape

and outsmarted them. Finally, to take revenge on him, the brothers pushed him

into a deserted-well. In the well, there lived a one-eyed demon, a pigeon and a

serpent, and they used to go out in day time and

return in dark. He overheard their conversation - the serpent admitted that he

is in possession of treasure of seven kings; the demon claimed that the King’s

daughter is always ill because she is possessed by him; and pigeon revealed

that his droppings can cure any diseases. The boy managed to escape on the next

day with some quantity of pigeon’s droppings and came to the palace to cure the

King’s daughter. As promised, the King gave him a half of the kingdom, and made

elaborate arrangement for his marriage with the King’s daughter. On the wedding

day, the wicked brothers were also present in the palace. They stopped the

marriage by telling the King that the half-a-boy was not suitable as he was a

son of a scavenger, and what did was not by him. Now the half-a-son had to

prove himself and he brought the treasures from the well and married the King’s

daughter. But all the six brothers attempted to get into the well in search of

treasure and were killed by its inhabitants Steel

(1894) 275-283.

3)

Summary of “The Goose Girl”: from the famous collection of Brothers Grimm (1815): A young princess was sent to a faraway land by her mother, a widowed

queen. A charm was given to the girl to protect her as long

as she wears it, a magical horse, Falada who

can speak and a maid. On their way, the maid refused to serve the princess and

the princess lost her charm. The maid threatened her and reversed the role. In

the palace, the maid posed as princess and the princess as servant. The maid

did a lot of tricks to eliminate the princess. Finally, the King came to know

the truth and killed the maid as a punishment. The prince and princess married

and lived happily Ashliman (2002).

4)

Summary of “The Golden Bird”: Every year, the King’s apple tree is robbed of one

golden apple. The King asked the three sons of the gardener to watch and while

the two sons slept off, the third son managed to shoot the bird and only got

the feather off. After seeing the golden feather, the Kind asked them to get

the priceless golden bird at any cost. On their way a fox advised them which

was ignored by the two brothers and the third son obeyed it. The third son

found the bird, but his elder brothers pushed him into the river with the

intension of getting the reward. However, he managed to escape as well expose

his brothers, and eventually married the princess in a grand marriage. On

behest of the fox, he cut its head to release the brother of the princess who was

captivated by a witch for great many years Ashliman (2020).

5)

Summary of “The White Bride and the Black One”: A woman, her daughter and

stepdaughter were in the forest to collect fodder. The Lord appeared in front

of them and asked the way to the village. When both mother and daughter

refused, the stepdaughter showed him the way. As a result, the Lord turned her into

a beautiful girl, and daughter an ugly one. The King came to know through her

brother about the beautiful girl and wanted to marry her. When the King sent a

coachman to bring the beautiful girl, the mother put her daughter in the coach.

After seeing the ugly girl, the King refused to marry her. But the girl’s

mother persuaded the King. Meanwhile, everything was revealed, and the King

married the beautiful bride and punishes the mother and her ugly daughter Ashliman (2020).

3. Propp and Dramatis Personae

The summaries/abstracts of five examples given here show the occurrences of false hero with degree of variation in its configuration, but there seems to be a commonality on the condition of attempt at replacement of the hero. Whether they are heroes or false heroes, they appear in folktales in order to fulfil the assigned task - move the story on the particular narrative plot, in ending the story as well as constructing the message. Although Vladimir Propp (1895-1970), Russian folklorist, developed a taxonomic model based on the ‘irreducible narrative elements’ after going through one hundred Russian fairy tales, the dramatis personae and the functions could be found their relevance in almost all folktales across the societies. After The Morphology of Folktale first appeared in 1928 in Russian language, it took almost thirty years for the rest of the world to get its access to it with the English translation that appeared in 1958. The Proppian taxonomic model proposed in the book found its relevance in understanding many aspects of narrative structures – in terms of universality with cultural differences. Thus, the model was found to be fascinated among folklorists, linguists, and others who were engaged in different types of narratives. Propp’s structural analysis of folktales that proposed the essential thirty-one functions or popularly known as “narratemes” could not been seen as merely reductionism or a kind of exclusivism since it appeared to be of disregard of historical and contextual information. Further, it has also been understood that his model is devoid of things other than the elements that are associated with the surface structure. After going through hundred fairy tales [since ‘fairy-tale’ belongs to the folktale genre, the term ‘folktale’ is used here], he realized the need for breaking down them into components so that a structural comparison between tales could be possible. However, his idea that the folktales could be segmented in order to be compared cannot be considered either as unscientific or unanalytical, since its great influence on various fields of approaches to narratives structures proved to be historical and revolutionary. According to Propp “If we are incapable of breaking the tale into its components, we will not be able to make a correct comparison. And if we do not know how to compare, then how can we throw light upon, for instance, Indo-Egyptian relationships, or upon the relationships of the Greek fable to the Indian, etc.?” (1968:15). He says further that “The result will be a morphology (i.e., a description of the tale according to its component parts and the relationship of these components to each other and to the whole)” Propp (1968) 19. Before proceeding, there is a need to wrap up with a few references to the Proppian proposal of the taxonomic model. Although his taxonomic model is founded on a set of four criteria, his definition of function gains significance since it bifurcates between action and their actions, that is, the function as “an act of a character, defined from the point of view of its significance for the course of the action” Propp (1968) 21.

Propp’s

functions of the dramatis personae

can be given as follow: Initial situation (α); 1. One of the members of a

family absents himself from home (Assentation, β); 2. An interdiction is

addressed to the hero (Interdiction, γ); 3. The interdiction is violated

(Violation, δ); 4. The villain makes an attempt at reconnaissance

(Reconnaissance, ε); 5. The villain receives information about his victim

(Delivery, ζ); 6. The villain attempts to deceive his victim in order to

take possession of him or of his belongings (Trickery (η); 7. The victim

submits to deception and thereby unwittingly helps his enemy (Complicity,

θ); 8. The villain causes harm or injury to a member of a family

(Villainy, A); 8A. One member of a family either lacks something or desires to

have something (Lack, a; 9. Misfortune or lack is made known; the hero is

approached with a request or command; he is allowed to go or he is dispatched

(Mediation, B); 10. The seeker agrees to or decides upon counteraction

(Beginning counteraction, C); 11. The Hero leaves home (Departure, ↑);

12. The hero is tested, interrogated, attacked, etc., which prepares the way

for his receiving either a magical agent or helper (First function of the

Donor, D); 13. The hero reacts to the actions of the future donor (The hero’s

reaction, E) 14. The hero acquires the use of a magical agent (Provision of a

magical agent, F); 15. The hero is transferred, delivered, or led to the

whereabouts of an object of search (Guidance, G); 16. The hero and the villain

join in direct combat (Struggle, H); 17. The hero is branded (Branding, I); 18.

The villain is defeated (Victory, J); 19. The initial misfortune or lack is

liquidated (Liquidation of Lack, K); 20. The Hero returns (Return, ↓);

21. The Hero is pursued (Pursuit, Pr); 22. Rescue of

the Hero from pursuit (Rescue, Rs); 23. The hero, unrecognized, arrives home or

in another country (Unrecognized arrival, O); 24. A false hero presents

unfounded claims (Unfounded claims, L); 25. A difficult task is proposed to the

hero (Difficult task, M); 26. The task is resolved (Solution, N); 27. The Hero

is recognized (Recognized, Q); 28. The false hero or villain is exposed

(Exposure, Ex); 29. The hero is given a new appearance (Transfiguration, T);

30. The Villain is punished (Punishment, U); 31. The Hero is married and

ascends the throne (Wedding, W). (Greimas revealed

the presence of ambiguity in The Morphology because the term dramatis

personae initially describes the “actors” and subsequently describes the

“actants.” But by following Propp’s own suggestion, he reduced the thirty-one

functions to twenty functional categories with the following coupling: Fn3 Vs

Fn4; Fn6 Vs Fn7; Fn8 Vs Fn8A; Fn9 Vs Fn10; Fn12 Vs Fn13; Fn16 Vs Fn18; Fn21 Vs

Fn22; Fn25 Vs Fn26; Fn28 Vs Fn29; and Fn30 Vs Fn31 – other functions remain the

same.) Ramakrishnan

(1997).

4. Towards Actantial Structure

The

identification of ‘narrative functions’ or ‘units’ must be seen as an attempt

to conceive narratives as broader as possible, thus he admits that some of the

actions found in folktales may not conform to the list of functions mentioned

here. However, this model is useful in developing and proffering a mathematical

formula for a given folktale by way of reduction and use of symbols of

designation. Moreover, these functions are regrouped under the seven spheres of

the dramatis personae: I. The sphere of action of the villain; II. The sphere

of action of the donor; III. The sphere of action of the helper; IV. The sphere

of action of a princess; V. The sphere of action of the dispatcher; VI. The

sphere of action of the hero; and VII. The sphere of action of the false hero.

Further, Greimas proceeded to formulate an actantial model of narratives by reducing the seven spheres

of action into a maximum of six actants and presented in three pairs on the basis of the logic of syntax (Proppian correspondence

given within brackets): Subject Vs Object (Hero Vs Sought-for-Person); Sender

Vs Receiver (Father/dispatcher Vs Hero); and Helper Vs Opponent

(Helper/provider Vs Villain or False hero). It is also understood that one

actant is conceived of subsuming two actors, and although it is already

reflected in the function ‘28 (Ex) Exposure – the false hero or villain is

exposed’, the actantial model amalgamated it with the

opponent which represented the inclusiveness in accommodating both the villain

and false hero. There is an advantage in the process of reduction as long as the subsumed categories are having common

attributes and having same modal existence.

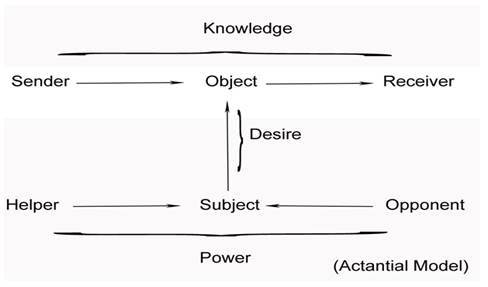

An actantial model developed from the three pairs of actants,

as given below, could be seen reflecting three levels of relationships of

orientation such as ‘knowledge’, ‘desire’ and ‘power’: Figure 1

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 Actantial Model |

Greimasean

semiotic square, the visual representation of the logical articulation of any

category in terms of relations of contrariness, contradiction, and implication.

The whole model implies that the narrative text is action oriented on the one

hand and having a complex set of passional dimension on the other hand.

Moreover, Greimasean theory of action could be seen

as treating subjects as active cognitive beings endowed with character and

temperament. In the context of narrative subjects, the passional configurations

could be defined as a “tendency to”, “feeling that leads to” or “the inner

state of one who is inclined to” etc., and the “tendency” expressed in terms of

behaviour or action, then the tendency could lead to a “doing” – a legitimate

supposition that can imply a certain regulation of “being” with a view towards

“doing.” The narrative theory of Greimas convinces by

considering passion as or on the syntactic organization of the state of mind

and it leads to the assumption and treatment that the discursive aspect of the

modalized being of narrative subjects of passions, either simple or complex,

are expressed through actants/actors along with actions to determine their actantial and thematic roles. The modal existence of the

subjects and modal components of the actantial

structures explain some aspect of the narrative semiotics proposed by Greimas, which identifies a limited series of roles of the

subject that characterize various modes of existence of the narrative actants

during their transformation. Thus, on this line of thinking, there are four

modes of existence of the subjects could be comprehended within the actantial structure: Virtualized subject (as a

non-conjoined category); Actualized subject (as a disjoined category); Realized

subject (as a conjoined category); and Potentialized subject (as a

non-disjoined – this fourth position is developed by negating the actualized

subject with the presupposition of the realized subject). The following are the few examples of the

subjects of state’s modal existence:

‘Wanting-to-be

(desirable for the subject of state)’

‘Having-to-be

(indispensable)’

‘Being-able-to-be

(possible)’

‘Knowing-how-to-be

(genuine)’ Greimas (1987)

The

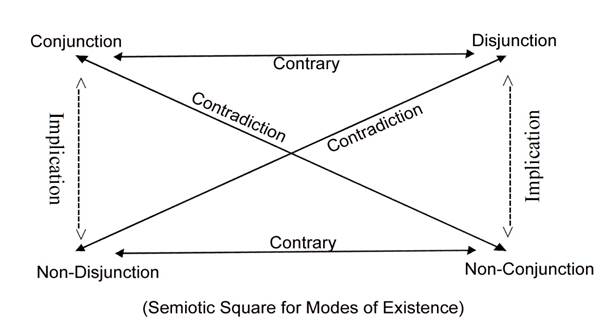

semiotic square for the modes of existence can be given as below: Figure 2

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 Modes of Existence |

If

Conjunction is considered as S1, Disjunction as S2, then the neutral axis of non-Disjunction

as –S2, Non-Conjunction as –S1 can be drawn in which S1, S2 are contrary terms,

-S2, -S1 are the contradictory terms and S1 and –S2; S2 and –S1 are the

complementary terms. However, these four terms inter-define each other Greimas (1970) 163. The four terms with two operations such as contrary and contradictory

other terms are obtained Greimas (1987) 50. The metaterms are created with the help of the combination of

two terms using + marks, for example, -S2+-S1. For Greimas,

signification is carried at the level of the structure, not at the level of the

elements, so the elementary signifying units must be sought (1983: 20). For Greimas, as Janicka mentions that

“Language is not a system of signs but an assemblage […] of structures of

signification” (1983:3, cf Janicka

2010:46). The interesting aspect of the modes of existence of actants is that

it offers some amount of space for philosophical assumptions on certain notions

associated with terms like agent, object, modalization

and actualization. In fact, the state of the subject in terms of modalities

could be seen as laying foundations for the semiotics of passion which

paradoxically a phenomenon in which the object is becoming a value for the

subject and by which the object imposes itself on the subject. Once the object

becomes an object of value and the subject becomes a subject of the quest, then

the sender and the receiver play different roles in the trajectory of passion –

for example, while the receiver is directly concerned with the passion, whereas

the sender happens to be at the origin of the programme (in many of folktales).

5. Action as syntagmatic organization of acts

The action

is conceptualized as the syntagmatic organization of acts – the opposition

between actions within the narrative schema. Here, Greimasean

passion represents the conversion of the discursive level of the deeper and

more abstract opposition between being and doing. The being of the subject is

modalized by the modality of ‘wanting’ which is actualized

(‘wanting-to-be-conjoined’) to a realized subject, that is, to be conjoined

with the object-of-value. The modalization of ‘being’

of the subject is an essential aspect in the constitution of the competence of

the syntactic subject where the subject’s relations to the object is mediated

by the body which is the part of the world as well as of the subject, and the

body is also seen as the object situated between other objects and the world.

Here the body is also conceptualized as action on the world and

also a perceiving, a sensing of the world. The subject in the narrative

syntax is handled by Greimas in terms of the

terminology of performance that differentiates the status of the subject as the

subject of doing and the subject of being. But with the logic of

presupposition, the subject of doing is always considered as possessing a

required competence for doing. There are folktales that provide evidence for

the claim that the subject’s competence is acquired only with the help of a

simulated performance of some other subjects. Further, if subject’s passion is

the result of a doing, either by itself or by other subjects, it can be led to

an act, or a “speech act” – the subject of “envy” as a subject of state, for

example, is affected by passion itself Ramakrishnan

(1997) 18.

The

acquisition of competence by a subject depends on being-able or knowing or both

successively; and the competence in the narrative level is based on wanting,

being-able or knowing-how-to-do of the subject; and the competence presupposes

performative doing or in the semiotic system, the production of an act of

parole presupposes the existence of a langue. That is, the performance of a

signifying subject presupposes the competence of that signifying subject. Here,

both lexicology and narrative are associated with the passion that produces the

structure of actions, for example, offence provokes a desire for revenge that

logically turns into a set of actions of vengeance – at another level – the

trajectory of acts of emotion can be seen in parallel to the trajectory of a

folktale, that is, a beginning, its development, its peak, and its end.

However, there is a complication in understanding the actants or subjects

because some of them, for example a subject ‘hero’, do not remain a subject all

the time – it changes along the narrative route, or being a hero only at a

given moment. It helps us to understand that in semiotics of narratives, there

is an organization of positions and no longer of characters. That is, the actor

is empty continuum that is progressively filled, and sometimes two subjects can

be put into it. However, a subject’s semiotic existence is guaranteed by

conjunction of the subject with its objective-of-value. According to Greimas, this is reflected in the characterization of the

subject of state in terms of opposition in the following way Greimas (1987) 151:

1)

At semio-narrative level: /Disjunction/ Vs

/Conjunction/

/Actualized/ Vs /Realized/

2)

At discursive level: /Tension/ Vs

/Realization/

/Expectations/ Vs /Satisfaction/

6. Conjoining with the Object-of-Value

The

relationship between ‘being’ subject, ‘doing’ subject and the sought-for-object

can be understood with the help of modality of subject or mode of existence. It

is appropriate that the subject that wants to be conjoined with the object and

the subject that is facilitating the conjoining must be explained. Subject of

the state (S1) is aiming to conjoin with the object-of-value and

this wanting can be represented in the diagram as follow: (S1)

wanting (S2)

−−−−−−−−> (S1 n Ov). Here

the subject of state can display a two-fold relation – its relation

with the object-of-value on the one hand and with the state-of-doing on the

other hand. Further, the subject of state’s expectation on

the subject of doing for the realization cannot be considered as a

simple, rather it can refer to the “rights” or “fiduciary” or on the “contract

of confidence” or a “pseudo-contract” (a quasi-contractual relationship between

the subject-of-state and the subject-of-doing). This expectation is not based on a true contract rather

an imaginary one, however, in the case of true contract, it is a matter of

confidence that emerges because of spontaneous or repeated experience – the

repeated experience of the subject with other subjects or with the same

subject. This formulation can be represented as S1 believing S2

having to −−−−−−−−> (S1

n Ov) Greimas (1987) 152. The

lexicological and narrative association can be seen in the following example:

Going by the word expectation there is an involvement of two things such as

‘patience’ and ‘impatience’ and among these two, while the former reflects the

state of mind of the one who knows to wait without, and the latter refers to

the failure in the patience. The occurential events

of folk narratives have express the parallel with the lexicological structure

of any passion. At the performances of narrative, the syntactic trajectory can

be drawn as follows: wanting à knowing à being-able ==>doing. The

acquisition of modal value of being-able of the subject makes it to become an

operator able to accomplish the performance. In narrative structures, there

exists a paradigmatic relational network in which the elementary structure

articulates signification into isotopic sets for the semiotic square, where it

is possible to find both the positive deixis (S1 + S2-)

and the negative deixis (S2 + S1-). Here we are able to produce a doubling of actantial

structure in which each actant can be referred to one of the two deixes to get the following distinction:

Positive

subject Vs negative subject (or anti-subject)

Positive

object Vs negative object

Positive

sender Vs negative sender (or anti-sender)

Positive

receiver Vs negative receiver (or anti-receiver) Greimas (1987)

7. Towards the Semiotics of the False Hero

The

narrative evidence is given here to ascertain that the false hero is a

narrative reality, and it is also a social reality if we observe our daily

life. The appearance of false hero could be evidenced in different places in

the (folk) narrative structure and thus, the chronological order of the linear

sequence of elements in the folkloristic text might present the false hero at different places

depending on the narrative requirements. So, the description of a tale from A

to Z, as part of the structural study, could comfortably expose the

occurrence(s) of false hero as one type of structural arrangement. The

syntagmatic and the paradigmatic approaches applied to the folk narrative

structures were generally considered in terms of ‘concern or lack or concern

with context’ Propp 1928: 2, tr. Propp (1968). Propp bothered the structure of text that is the

text is in isolation from its social and cultural context. Conversely,

Levi-Strauss in his paradigmatic analysis related myth with other aspects of

culture such as cosmology and worldview – the new notion of myth emerged as a model

due to his brave attempt Propp (1968). In fact, it was criticized that Propp failed to

relate his morphology with the Russian culture as a whole.

However, adding context to paradigmatic analysis is one of the methods rather

than one inherent in it. Can’t we say that some of his functions are culturally

structured, or culture has something to do with the functions? Yes, obviously

that without cultural orientation the functions like wedding cannot be

structured. So, it is explained that the syntagmatic structures – like wedding,

formation of a new family, ascending the throne – of folktales are meaningfully

related to aspects of a culture such as social structure Propp (1968). Many folktales reflect Von Sydow (1948), Propp (1968) notion of oicotype -

defined or understood as ‘a recurrent, predictable cultural or local variant -

can be found in many of the syntagmatic structure of folktales. It is important

to note that since ‘culture patterns normally noticeable in a variety of

cultural materials’, the Proppian model can be applicable beyond the fairy

tales.

The

orientation regarding the nature, structure and function of narratives has been

changed with the development of narratology. Since the narrative reality,

though imaginary or sometime based on reality, cannot be seen away from the

social reality, that is, the narrative world cannot exist in the absence of

social world. However, the narrative elements collectively involve in the

construction of the narrative on the one hand and on the hand, they help to

project the message for the purpose the whole narrative. In this background,

the seventh element of the dramatis

personae, the sphere of action of the false hero cannot be ignored but must

be given attention. From the five examples given here both the constants and

variables can be identified – a task is performed someone and claimed by

someone else. (Ref.: tale 1. A scavenger takes the head of the ogre killed by

the younger prince and went to claim half of the kingdom and the King's

daughter in marriage; tale 2. The brothers of the prince-half-a-son approach

the King and inform him that the tasks are not performed by their brother, so

he is not entitled for the reward; tale 3. The maid of a young princess claims

that she is the princess to marry the prince of the remote country; tale 4. The

elder brother claims the task and wants to receive the reward; and tale 5. The

ugly stepdaughter who tries to be in the place of her beautiful sister for

marrying the King was revealed later and she is being punished for that.) [“1.

A tsar gives an eagle to a hero. The eagle carries the hero away to another

kingdom; 2. An old man gives Súcenko a horse. The

horse carries Súcenko away to another kingdom; 3. A

sorcerer gives Iván a little boat. The boat takes Iván to another kingdom; 4. A

princess gives Iván a ring. Young men appearing from out of the ring carry Iván

away into another kingdom, and so forth” Propp (1968). While these are good examples given by Propp for

the constants and variables, our examples must be seen as indicative.] Thus,

one could notice that there is a change in the names of the dramatis personae and their change in

attributes, but their actions and functions of claiming the reward do not

change. Therefore, on the basis of the suggestion

given by Propp, we can proceed to study the folk narratives according to the

functions of its dramatis personae.

At this moment, we are provided with three elements to study: the folk narrative as a whole, functions of dramatis personae, and the nature and condition of the dramatis personae. For Propp, the

functions are basic components of narratives, and thus they must be defined

first in order to be extracted from the folktales. A

function is consisting of a form of a noun expressing an action and its place in the course of narration, and in other words, “[f]unction

is understood as an act of a character, defined from the point of view of its

significance for the course of the action” Propp (1968).

Interestingly,

the false hero, at this juncture, could be seen as emerging as a ‘sought for

the person’ or the ‘object of necessity’ and in accomplishing it or achieving

it, one may need a metaphorical helper to overcome the metaphorical villain. Greimas has simplified the role of the false hero within

the Actantial model by merging it with that of the

opponent, and whereas, both the opponent and the false hero are separate

entities within the thirty-one functions or seven dramatis personae of Propp.

If Greimasean opponent becomes an actantial

category, then the opponent as an actant must be understood, but prior to that

the definition of actant and its inevitable role in combining both actor and

action must be presented. It is by drawing input from the Semiotics and

Language – An Analytical Dictionary of Greimas and Courtés

(1982), ‘action’, ‘actor’ and ‘actant’ are defined here.

Here action refers to the ‘syntagmatic organization of acts’ and

also the ‘result of the conversion of a narrative programme,’ and here,

‘the subject is represented by an actor and its doing which is converted into a

process’ (1982: 6-7). Similarly, ‘the actor, who may be an individual, or a

collective or nonfigurative, as a historical replacement of character and

dramatis personae to be a lexical unit’ is also acknowledged here. Moreover,

the actor is seen as the point of convergence and investment of both the

syntactic and semantic components, and further, it is also the transformation

of roles – the interplay of successive acquisition and loss of values. And

interestingly, an actor is the product of discourse, and it involves in the

distinguishing process between the subject of the enunciation and also as the point of enunciation’ Greimas and Courtés

(1982). Between actor, action and actant, there lies actorialization as a linking factor which is defined as

‘one of the components of discrimination that is based on the implementation of

the operations of engagement and disengagement. The actorialization

aims at establishing the actors of the discourse by uniting different elements

of the semantic and syntactic components. These components unfold their actantial and thematic trajectories in an autonomous

manner, and at least one actantial role and one

thematic role constitute the actors which are thus endowed at one and the same

time with a modus operandi and a modus essendi’ Greimas and Courtés

(1982).

The actantial model is constituted with maximum of six actants

with their orientation towards each other, but the question on the false hero

is yet to be answered. The false hero is a strange character not only in the

narratives but also in daily life. The function of the false hero in all the

sample narratives seem to be the same, but the attributes associated with each

of them vary drastically and they can be seen emerging from three sources:

known person (e.g., maid), unknown person or stranger (e.g., scavenger), and

relatives (e.g., brothers, stepsister, stepmother). If the false hero is

considered as one of the stock characters as far as folktales are concerned,

then how does it seem represent the social reality? Unlike villain, or Greimasean opponent, the false hero never wanted to have a

direct encounter with the hero or Greimasean subject.

However, keeping object at the centre, all the actantial

agents would be defined, for example, the Sender is the one directing the

subject towards the object; the Receiver is the addressee of the sender; the

Subject is the centre of the whole narrative schema – it is directed by the

sender, opposed by the opponent, helped by the helper, or received by the

receiver or by other objects to become the receivers themselves, or takes the

reward when object is received by the receiver, and it develops a kind of

desire towards the object; the Object is the one that is sought by the sender,

the subject and the opponent; the Helper is the one helps the subject to reach

the object; and the Opponent is the one to block the subject from reaching the

object. If false hero also does the role of blocking the subject to reach the

object, like the opponent, or villain in Proppian term, then how does he emerge

as a false hero? In folktales, the false hero makes entry either in the

beginning or in the end of the narrative. If it happens in the beginning, the

whole narrative moves around to expose the false hero. But if it happens in the

end of the narrative, then the false hero blocks the subject reaching the

object by making a claim and deceiving the opportunities of the subject or the

hero. At this moment, there are three agents such as the subject (the hero), the

opponent (villain) and (the false hero) – (the false hero is given without its

parallel in Greimasean actantial

model, because the opponent is conceptualized as a broader category).

8. The Subject (Hero) and the Opponent (Villain) Vs the False Hero

The

definitions given by Greimas and Courtés

(1982) offer clarification between the hero, villain, and

false hero. Let us begin with the subject: The subject is situated at the

crossroads of different traditions and due to prevailing ambiguities, it is

difficult to handle it. However, it is an observable entity and objectivized

utterance. Philosophically, it refers to a "being" to an "active

principle" capable not only of having qualities, but it is also of

carrying out acts. They are the speaking subject in linguistic terms and

knowing subject in epistemological perspective. The subject is an actant to

function as per it is inscribed. The actantial

grammar renders the status of the subject relative and thus it can go beyond

the subject as substance. Corresponding to the phrastic subject and discursive subject, there are

another two types of subjects such as the subject of state (based on the

elementary utterance – the utterance of state or being) and it is characterized

by a relationship of junction with objects of value and the second type of

subjects of doing (based on the elementary utterance of doing) – defined by the

relationship of transformation. Further identification of distinctive

dimensions could lead to the establishment of a distinction between phrastic subjects and cognitive subjects – that are

specified by the nature of the values. Finally, the narrative schema defined as

a hypothetical model of the general organization of narrativity produces

subject that conceives its life as a project, realization, and destiny. This

semiotic subject is inevitably divided paradigmatically into at least the four

positions of the semiotic square. (anti-suject,

performing subject, competent subject) Greimas and Courtés

(1982). The definition of hero found in the Analytical

Dictionary adds clarification for both the terms. The term hero is used to name

the subject actant in a certain position on its narrative trajectory

corresponding to its moral values. That is, the subject has

to become a hero by the condition of possessing certain competency of

‘being-able’ or ‘knowing-how-to-do’ and thus, the hero is simply the name of a

specific actantial status. There are different types

of hero emerge in a narrative trajectory depending on the status at a given

point, further depending on the pragmatic and cognitive dimensions. For

instance: the pragmatic dimension differentiates the actualized hero (seen

before its performance of required tasks) from the realized hero who is now

possessing the object of the quest; and from the cognitive dimensions

differentiates the hidden hero form the revealed hero who receives the sender’s

cognitive sanctions, or recognition. So, the term hero is given to the subject

actant, but endowed with moralizing euphoric connotations – that is, the hero

is placed in opposition to villain, a disphorically

connoted element in a narrative. Greimas and Courtés

(1982)

Villain,

for Propp (1958) 79 has to

display the villainy - a fight or other forms of struggle with the hero. The

villain sometimes emerges as an anti-donor (the hero receives competence from

the donor which is necessary for the former’s performance) to be homologated

with the opponent who creates the essential function of lack that creates

narrative’s “movement” (as called by Propp). The villain’s action is

responsible for the negative transformation which necessitates a positive

transformation as counterbalance. This polemic structure that is the result of

the presence of double narratives created by both the hero and the villain

makes the folktale not as a homogenous whole. That is, from the syntactic

perspective, there are two narrative trajectories – one initiated by the

subject (the hero) and another by the anti-subject (the villain) and they are

opposite and complementary. These parallel narratives are differentiated in reality only by their euphoric or dysphoric moralizing

connotation. Although the Proppian hero is positively overdetermined (in

contrast to the villain who is negatively overdetermined), but the villain is

qualified as hero whose heroic quality is always proved because whose is

involved in deceptive tests Greimas and Courtés

(1982) 370-371.

The six

agents present in the actantial model are considered

as more accommodative and inclusive, but there must be a discussion on how to

fix the false hero and the villain within the opponent? They may appear as

opponent in one way or the other, but the configuration of them may emphasize

the presence of differences. Going by the Analytical Dictionary, ‘the

opponent is defined as the role of negative auxiliant

taken up by the actor other than the subject of doing and it corresponds to an

individual not-being-able-to-do which thwarts the realization of the

narrative programme in question’ Greimas and Courtés

(1982) 220. And

further clarification on the nature of opponent could be drawn from the entry

of ‘opposition’ given subsequent to the ‘opponent’

within the same page. According to the Analytical Dictionary,

‘opposition is an operational concept that is used to designate the existence

of any relation between two entities having sufficient reason to consider them

together. (Verses (vs) or the oblique bar (/) are used to represent such a

relation.) The opposition established on the paradigmatic axis, or the axis of

opposition or axis of selection reflects the ‘either… or’ relation which is

distinguished from the syntagmatic axis, or the axis of contrasts indicated

with ‘both... and’ Greimas and Courtés

(1982) 220.

The

definitions and explanations given here facilitate our better understanding of

the notion of false hero which differentiates itself from the hero by the

prefix of the false and distinguishes itself from the villain by possessing the

term hero. It is neither a hero nor a villain, but it is as an opponent as per

the actantial model. The status of an opponent

becomes problematic when it accommodates both the villain as well as the false

hero who has to be exposed rather than countered by

the hero. However, the villain is assumed to possess an equal competence and

strength to oppose or block the activities of the hero, or to initiate a lack

that can activate the hero in the narrative trajectory. That is, the disequilibrium

can be seen between the false hero and the villain in terms of competence and

strategy. Thus, the use of the term opponent is conceived as a structural

arrangement with symmetrical elements to balance it. In some of the examples,

the false heroes occupy the whole narrative by performing the villainy, but in

the end of the narrative their identities have been exposed, whereas in the

case of villain there is no need of exposition of (non-present) false identity.

From the given examples, though they are given in limited numbers, the quality

of the false heroes is constructed in such a way that their qualification for

conjoining with the object of value is not validated and justified. Even the

nature of introduction of the false heroes, for example, as a scavenger, as an

ugly stepsister, as undeserving brothers, and as a maid, never fails to reveal

their inherent quality for achieving the object or seeking the reward.

Therefore, there are examples that show that the heroes have

to have fighting on two fronts – with the villain on the one hand and on

the other hand with the false heroes, who accidentally get a chance to claim

for the reward or in other way, the status of the hero. That is, while villain

needs to defeat, the false hero must to be exposed.

Further, on the moral ground, the villain with strong characters that

considered as equal to the hero, has motivations that are utterly evil and

beyond redemption, whereas the false hero characters are weak, immoral but not

self-evidently evil.

The existence

of false heroes in folktales or any narratives cannot be considered as unreal

or imaginary. In daily life, the villains are metaphorically reflected in terms

of hurdles that have to be overcome through hard work

and efforts, but the false heroes are those who accidentally or intentionally

appear to snatch the hard yearned rewards, or opportunities or chances, by

whatever means. In real life, the success of a false hero, that is evident in

corrupt and immoral societies, by successfully bypassing the regularities or by

visibly violating the procedural designs or manipulating the elements of

system, could be seen leading to the deterioration and derailment of the system

through the visible and invisible legitimization of unethical manifestations.

So, the successful false hero, in real life and outside the narrative paradigm,

enjoys the power and benefits that are not meant for it and

also the false hero, to continue to enjoy the power and benefits, makes

efforts to legitimize its position by compromising on various fronts. That is,

as far as the life of the false hero is concerned, there is a dichotomy between

real life situations and the narrative life: while the false hero enjoys the

power and benefits in real life, it is exposed and punished in narratives.

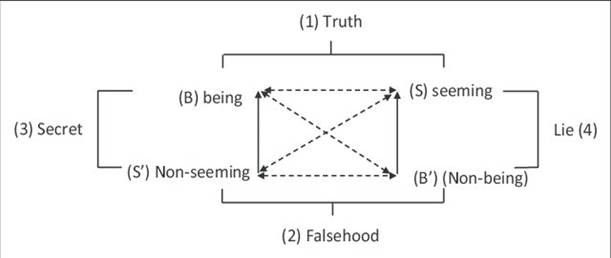

Therefore,

the falseness of a false hero is not a simple term rather it is complex one as

it includes both the non-being and non-seeming on the axis of subcontraries in

the semiotic square of the veridictory modalities. Greimas who developed the veridictory

square noted that the “truth values” of the false are situated within the

discourse during the veridiction operations and that cannot be related to

outside the discursive structure Greimas and Courtés

(1982) 116. Similarly,

truth is also a complex term that accommodates the being and seeming on the

axis of contraries as per the veridictory modalities

and it makes our understanding that ‘truth’ is found in the discourse without

having the external referent Greimas and Courtés

(1982) 369. The veridictory square of Greimas is

presented here Greimas and Courtés

(1982) 310 Figure 3:

Figure 3

|

Figure 3 Veridictory

Square |

The nature

of ‘falsehood’, ‘truth’ along with ‘secret’ and ‘lie’ are reflected and their

positions and interrelationships are presented in the square. The falsehood is

an issue not only in the narrative paradigm but also in the real-life scenario.

The villains seem to acquire concerns on the ground that unlike false heroes,

they develop their competence to have direct encounters with the hero. On the

other hand, the source of the emergence of false heroes is noteworthy as it

warns that the falsehood or falseness or false claim is more problematic not only

in folk narratives or narrative discourse, but also in socio-cultural life.

9. Conclusion

With the help of few folktales as examples, this article attempted to evaluate the nature of the category called opponent within the Greimasean actantial model, in terms of the villain and the false hero. Although both the villain and the false hero within the narrative paradigm occupy the role of an opponent, they differ from each other in terms of veridictory modalities of truth and falseness. Though these characters have been discussed within the narrative context or discursive structure, the existence of these characters cannot be ignored in real life – which makes us to claim that many of the characters found either in the folk narratives or any narratives structures cannot be simply discarded as they are imaginary and as they do not have any similarity or relevance for the real society. The move between narrative world and real world with the help of “characters” or dramatis personae or actants is an essential task with which not only a large corpus of narratives [that occupy print, visual m and digital media] can be understood, but the real life can also be meaningful.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Ashliman, D. L. (2002). The Goose-Girl. University of Pittsburgh.

Ashliman, D. L. (2020). Grimm Brother's Children's and Household Tales (Grimms' Fairy Tales)". University of Pittsburgh.

Dogra, S. (2017). The Thirty-One Functions in Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale : An Outline and Recent Trends in the Applicability of the Proppian Taxonomic Model. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 9(2), 410-419. https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v9n2.41.

Dundes, A. (1964). The Morphology of North American Indian Folktales. Helsinki : Folklore Fellows Communications, 81(195).

Dundes, A. (1968). Excerpts from : Vladímir Propp Morphology of the Folk Tale 1928. Tr. The American Folklore Society and Indiana University.

Greimas, A. J., and Fontanille, J. (1993). The Semiotics of Passions : From States of Affairs to States of Feeling. Minneapolis and London : University of Minnesota Press.

Greimas, A.J. (1987). On Anger : A Lexical Semantic Study, in on Meaning : Selected Writings in Semiotic Theory. London : Frances Printer.

Greimas, A.J. (1987). On Meaning : Selected Writings in Semiotic Theory (Open linguistics series). London : Frances Printer.

Greimas, A.J. and Courtés, J. (1982). Semiotic and Language : An Analytical Dictionary. L. Crist, et al. Tr. Bloomington : Indiana University Press.

Greimas, A.J. (1966). Structural Semantics : An Attempt at a Method. London : University of Nebraska Press.

Herman, D. (2000). Existentialist Roots of Narrative Actants. Studies in 20th Century Literature,24(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1484.

Hébert, L. (2019). "The Veridictory Square" in An Introduction to Applied Semiotics : Tools for Text and Image Analysis, 29-35.

Myers, S. (2014, April 24). Vladimir Propp’s “31 Narratemes” : Another approach to story structure. Go Into the Story.

Propp, V. (1968). Morphology of the Folktale. Trans. Laurence Scott, revised Louis A. Wagner. Austin : University of Texas Press.

Ramakrishnan, M. (1997). Semiotic and Cognitive Study of Folk Narratives of Southern Tamil Nadu (Unpublished dissertation). New Delhi : Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Ramakrishnan, M. (2002). Conceptualization and Configuration of Body, Emotion and Knowledge in Narrative Discourses with Special Reference to Tamil Ballads. (Unpublished dissertation) New Delhi : Jawaharlal Nehru University. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/29134.

Sydow, C. W. (1948). Selected Papers on Folklore. Copenhagen : Rosenkilde and Bagger.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2022. All Rights Reserved.