ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

Folk music of western Odisha ‘Ganda Baja’ The Tradition in Transition

1 Independent Scholar, Puttaparthi (A.P) – 515134, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

‘Ganda Baja’ is a hardly discussed topic in scholastic works of Indian folk music. It is one of the major and unique folk music traditions in western-Odisha folk culture. Presently, it is going through a phase of transition which could determine its very existence. The new generation constantly in a search to contextualize the music that would sound trendy to the present-day music market, yet it is searching scopes to reach a level in terms of music quality and to justify the core. On the other hand, the cultural elites trying to filter the music that would be conducive to proscenium, but the original music and musicians remain marginalized. With the notion of up grading music, somewhere the transition is causing a distortion to the music and rarely addressed with that gravity. However, the traditional musicians and their music have always been rooted in traditional aesthetics. This study addresses on few degenerative factors that causing a huge distortion to Ganda Baja in the process of transition. The distortions that need more scholastic attentions are (1) the changing styles of music performance practices and the platforms, (2) the music making with overridden musical assimilation, and (3) the changing connotations in the scholastic works. The Ganda Baja musicians are excluded in current cultural happenings. This study aims at bringing Ganda Baja and the musicians to limelight both in the music literature and cultural platforms. It invites scholastic attentions to way out solutions that would produce music without a distortion. |

|||

|

Received 25 May 2022 Accepted 08 August 2022 Published 11 August 2022 Corresponding Author Deep

Prajapati, prajanmusic@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i2.2022.144 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Folk Music, Ganda Baja, Tradition,

Transition, Distortion, Western-Odisha, Dulduli,

Cultural Demands |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

The folk

music of western-Odisha (India) is probably one of the few living musical

traditions that has endured over centuries in its practice and performance. It

encompasses within it a wide range of folk music with varied forms and sets a

cultural boundary or a distinct ethnic identity of its own. Also, it differs in

its usage, functionality, music making, cultural significance and so on.

Prominent among them is ‘Ganda Baja’. Presently, the ‘Ganda Baja’ is

widely known as ‘Dulduli’ (as a revised form

of Ganda Baja). Ganda Baja is widely practiced in the

socio-cultural life of the common folk of western-Odisha and highly embedded

within the socio-cultural life of its common people.

1.1. ‘GANDA BAJA’ MENTIONED IN EARLY WORKS

There is just a handful of mentioning about Ganda Baja in folk music literature till date. Here and there we find some references by the colonial officials mostly on ethnographic perspective or few governments survey reports gazetteers. However, discussion on music aspect is very less. Here are few major early works that mention Ganda Baja. From these references one can see the profundity of Ganda Baja and can analyse its continually changing connotations and perspectives.

1.1.1. The early mentioning of ‘Ganda Baja’ in colonial narratives in 1916 by R V Russell.

“The Gandas are generally employed either in

weaving coarse cloth or as village musicians. They sing and dance to the

accompaniment of their instruments, the dancers generally being two young boys

dressed as women. They have long hair and put on skirts and half-sleeved

jackets, with hollow anklets round their feet filled with stones to make

them tinkle. On their right shoulders are attached some peacocks’ feathers, and

coloured cloths hang from their back and arms and wave about when they dance.

Among their musical instruments is the sing-bāja,

a single drum made of iron with ox-hide leather stretched over it; two horns

project from the sides for purposes of decoration and give the instrument its

name and it is beaten with thick leather thongs. The dafla is

a wooden drum open on one side and covered with a goatskin on the other, beaten

with a cane and a bamboo stick. The timki is

a single hemispherical drum of earthenware; and the sahnai is

a sort of bamboo flute.” Russell and Hiralal

(1916)

The description of Ganda Baja in this

work is just an overview. The used terminology ‘sahnai’

roughly used to refer the original instrument ‘Muhuri’

that is used in Ganda Baja and a sort of Sahnai.

However, it is possibly the earliest work that describes Ganda Baja.

1.1.2.

Sambalpur district gazetteer on ‘Ganda Baja’

“…..they also work as professional pipers and drummers and are employed

as musicians in marriage ceremonies…..…young girls move from village to village

singing and dancing accompanied by drummers and Ganda musicians.” Senapati (1971)

These are the descriptions about Ganda

Baja found in the post-independent government survey report that mentions

about Ganda Baja though it is in brief.

1.1.3.

Study of ‘Ganda Baja’ by Pattnaik and Mohanty in

1988

“The distinguishing and characteristic profession of Ganda as the

musicians is gradually becoming obsolete like other traditional professions i.e.,

weaving and watchmanship which were considered as low

social order in the traditional society. As the Gandas

are becoming more and more conscious about their social status, they are trying

to give up these disrespectful professions and social practices. However, the

Ganda musicians living in the urban centres have modernized their profession by

organizing themselves into sophisticate ‘Band parties’. They perform dances and

play music imitating the popular movie traditions during marriage ceremonies

and earn a good living.’’ Pattnaik and Mohanty (1988)

From 1016 to 1971 to 1988 there are big gaps of silence on Ganda Baja

in scholastic works. Yet it doesn’t mean that Ganda Baja

extinct from social practice. In the study of Pattnaik

and Mohanty, the transition and decadence of Ganda Baja was well

noticed. The transition we talk about Ganda Baja today started taking

place from that time.

1.1.4.

Phd research on ‘Ganda Baja’ by George Goldy

Later on in 2015 we come across a scholastic work which gives a more

space to discuss on Ganda Baja, highlighting its core value and tried to

bring a different worldview to Ganda Baja what was not written with that

importance in earlier works.

“…….gandabaja is an important symbol in the evolved identity of

the Gandas………Music and drumming had remained the core

thrust and heart of Ganda culture throughout the history. Cultural expressions

and art forms among Gandas are very vibrant and

sound. They had developed the music system (Baja) and enjoy the music and

rhythm on different social and ceremonial occasion. George

(2015)

1.1.5.

Ethno musicological study on ‘Ganda Baja’ by Dr

Lidia Guzy

“Ganda

Baja is probably the most prominent musical and ritual feature of the Bora

Sambar region. It is an instrumental orchestral music, performed

exclusively by musicians originating from the marginalized Harijan caste ‘Ganda’.”

Guzy (2013).

The study

of Ganda Baja by Guzy was an extensive field

study that I have witnessed personally. This study brought a whole new

perspective to Ganda Baja and made people aware about the inherent value

of the music that Lidia refers as sacred music. Also, in many discussions Lidia

Guzy has addressed the issues regarding the authentic

music and the transition leading towards a distortion.

1.1.6. WHAT IS GANDA BAJA IN SOCIO-CULTURAL PRACTICE? THE TRADITION, THE MUSICIANS, LOCALITY, AND CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE

Ganda baja is a folk music form which consists of a band of musicians with

instruments like a Dhol (membranophone),

pair of Lisan (single drumhead, vertical

face), a Tasa (single parchment), a pair of Jhumka

(shaker) and a Muhuri (pipe) played together.

This music is performed by a particular community of people called “Ganda”

(a sub-altern ethnic group, inhabitants of Mahanadi River valley) and they have

inherited the music as an ancestral legacy. Thereby, the music has got the name

“Ganda Baja”. ‘Ganda’ is the musicians and ‘Baja’ means

music.

Ganda

Baja is played in

dance, song, martial art, puppet art, trance, rituals, procession, and every

kind of social activity. Thus, it varies from its presentation. Mostly the

musicians play music with body movement, feet work and sometimes with

acrobatics. On certain cases they play seated also. One of their very common

presentation styles, in the very beginning the music starts with the tune of

Muhuri and the lead drummer Dhulia starts

the rhythm in a slow tempo of minimal strokes (alap

kind of free rhythm unfolding a structured rhythm) and gradually other

allied instruments get into the rhythm and give a vibrant climax. Various songs

and dance get involved. Mostly after the song stanza the rhythm leads to a

vigorous dance rhythm. When it is a ritual, the music goes as per situation and

also creates sad mood with uneven rhythmic meter and tune.

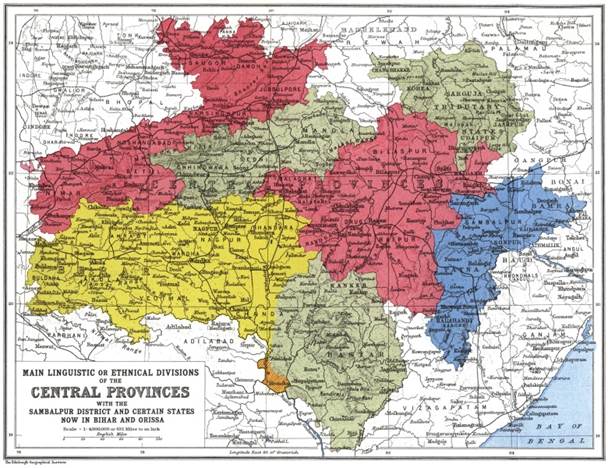

Ganda

Baja is widely practiced in the locality of Bargarh, Baud, Bolangir, Deogarh, Jharsuguda, Kalahandi, Nuapada, Sambalpur, Sonepur

and Sundargarh revenue districts that share a

common folk culture. The map below is taken from the book ‘The Tribes and

Castes of the Central Provinces, vol-I’ (an ethnographic survey by Government

of India in 1916, for the purpose of demarcating the major inhabitants in the

main provinces of India according to their ethnological accounts). The

powder-blue color part in the map is referred as ‘Uriya’ that refers to the present day western-Odisha. That

part of the map (powder-blue portion) shares a common folk culture and that can

be exactly mapped as the prevalent area of Ganda Baja musical tradition. Figure 1

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 An Ethnological Survey Map, The Powder-Blue Colour Demarcating Sambalpur Province (Present Day Western-Odisha) Of India Scale = 1: 4,000,000 or 63.1 Miles to an Inch |

Folk music

is an inseparable part in socio-cultural life of western-Odisha’s folk. Whether

it is a marriage ceremony or a birth celebration or any fair or festivals,

music is a must. For every occasion there is music. Any act of worship has some

music. No ritual is complete without music. Particular rituals have specific

rhythms for each and every rite. Even few instruments are used only for the

rites or rituals. Considering the importance of Ganda Baja there is a

proverb in local dialect that says, “agho baja, pachhe raja” meaning,

the music band is the first priority, king comes next.

“The Ganda

Baja is a ritual inter-village orchestra that carries with it indigenous

concepts of rhythms, instruments and goddesses, and is associated with marriage

alliances and religious ceremonies.” Guzy Lidia

In the

marriage ceremony of western-Odisha folk culture the Ganda Baja music is

an essential component and has a unique concept of Tera mangal (specific

rhythm for specific rites from the beginning to the end of the marriage

ceremony). The Ganda Baja serves as the Mantra which spreads

auspiciousness, gaiety, positivity, and moods of celebration as well as

emotion. The joy of rhythm compels some to move feet and pace the heartbeat

with the rhythm. The ambience of the music truly befits various moods of a

common folk like, the mental state to get ready for embracing a new stage of

marital life, welcoming a new member to the family and the warmth of meeting

kin and folks. As well as the melancholic tune of Muhuri

that leads its tune when the bride is about to leave for in-law’s house; can

make anyone tear eyed. This can only be felt by a participant observer that how

deeply Ganda Baja is bonded with human life. Today, this music has given

a cultural identity to its land and people which is touted to create a

demarcation for a separate cultural identity.

The

progenitors of the land have found the necessity of music in life and have

embedded all acts of life with the musical urge that has taken the shape of

folk music to what it is today. For the common folk of western-Odisha, the

experience of every aspect of life, such as, the celebration and sorrow,

prosperity and poverty, personal crisis, and collective joy; finds its

expression through the music that has developed with the flora and fauna of the

land where they are grown up with. Thereby, it has facilitated the creation of

an abundance of music for all aspects of life. Music, for them, has found its

role in public celebrations as well as in personal crisis. For those common

folk, music is a medium to communicate with Gods and Goddesses. Music plays its

role from the birth till the death of a person. The music is always associated

with nature and the music created thereby is a derivation from nature. It is a

common link between individuals, society, and nature. It is not an exaggeration

to say that Ganda Baja is the undiluted medium to understand

western-Odisha folk culture in its entirety.

“No culture

can be comprehended unless the music it produces is taken into account. Similarly,

no music can be understood without the help of the insights offered by the

parent culture.” Ranade

(1992)

But, in the

changing course of time, the tradition of music goes through a certain

transition in its practice, performance, function and as well as in

dissemination. Even, many music forms and music instruments go into oblivion,

unable to cope up with the taste of time. The folk music of western Odisha ‘Ganda

Baja’ is also not an exception.

2. TRADITION AND TRANSITION

The

following are the various styles of practice and performance of Ganda Baja:

1)

The

traditional form: Ganda Baja

2)

The

revised form: Dulduli

3)

Commercial

or semi-commercial music industry: Ganda Baja form presented in a

contemporary context of digital recordings

4)

The

‘glocalized’ form: the processional music, Band

Party/ Melody Band

2.1. Traditional form – Ganda Baja

·

In

its traditional form, the music is highly associated with socio-cultural life

of the people of western-Odisha. One can find this music in local fairs,

festivals, rituals, and ceremonies etc.

·

The

rhythm is the main component in music making.

·

The

music performance uses only traditional instruments like Dhol,

Lisan, Tasa, Muhuri and

Jhumka. No electronics or any synthetic

membrane is used in it.

·

The

performers typically belong to hereditary musicians that usually come from the

lower stratum (sub-altern) of their community. They carry the legacy of their

forefathers.

·

The

music is served in all other communities of the local culture.

·

The

music is for common masses and not performed specifically for an audience.

·

The

use of music is for local rites, rituals, religious ceremonies and even in

personal crisis. Certain rituals have specific ‘Paar’

(rhythm). Traditionally, most of the music is to be performed only for serving

that purpose.

·

The

music compositions are entirely anonymous; the music is credited to the

forefathers of that community.

·

The

music performance sometimes sounds like a raw form of music; still the

aesthetic appeal is high.

·

There

is an entertainment aspect of that music as well.

2.2. Revised form – Dulduli

·

Dulduli is the revised form of Ganda Baja that primarily

aims at bringing a cultural awareness and establishing a cultural identity or

in other words, cultural map of its own.

·

This

form of music is observed in cultural programs/cultural activities and mostly

it features in proscenium and screen/ digitized platforms to the extent it is

conducive.

·

In

Dulduli, the dance aspect is the major

component and rhythm is relegated to second position unlike it is in the

traditional Ganda Baja.

·

This

music is set to certain bars and pre-scored, yet often fails the traditional

charm and depth a traditional master can bring to it.

·

In

Dulduli a major portion of core music doesn’t

find space.

·

Dulduli is an open platform. Persons participating in Dulduli come from various strata of that society and

hence, this music form doesn’t suffer from derogatory feeling on participants.

This contrasts with Ganda Baja where the participants usually belong to

a lower stratum.

·

Dulduli has the flexibility to incorporate various elements and

instruments which are not found in traditional Ganda Baja. In most

cases, it is an assimilation of instruments outside the purview of Ganda

Baja with traditional instruments.

2.3. Ganda Baja-form presented in a contemporary context of digital recordings

·

In

the modern times, digitized music & platform have vastly influenced the Ganda

Baja folk music to transition it into a new form of Ganda Baja which

is substantially different from the original form.

·

Though

the music styles and patterns of Ganda Baja is the main source for

scoring or composing music in this new form, the need to popularise and

monetise music is changing the core form of Ganda Baja.

·

This

new form assimilates different music instruments from different genres.

Electronics and virtual music are also getting assimilated with traditional

music and instruments.

·

It

blends in it, different music parameters taken from different genres. Sometimes

one can observe shades of a raag from Hindustani repertoire, a piece of

choir or chords, or any other cross-cultural music piece.

·

In

few cases the traditional instruments are replaced with electronics or virtual

instruments. In few other cases, the original timbre property of a traditional

instrument is modified.

·

Since

the music is studio recorded, it demands a musician of studio experience rather

than a traditional drummer.

·

The

musicality and the audio engineering both play equal roles.

·

The

music has a target audience of young masses and more prone to digital content.

2.4. Band Party/ Local Melody Band

·

It

is absolutely a ‘glocalized’ form of music and has

come to this shape as per the current taste of common mass.

·

It’s

a band for processional music.

·

It

also allows non-traditional musicians to participate in it.

·

Mostly

the performers don’t tie the instruments to their body like traditional drummers

but play the instruments keeping it static in a stand support.

·

Often

it is seen that band groups use a large number of drummers which results in

creation of sounds rather than the musical finesse of the traditional one.

Thereby, music takes a different shape.

·

Mostly

the drummers prefer to use synthetic drums accompanied with electronics

instruments.

The change

in music is evident according to the societal changes from time to time.

However, music is the last thing to accept changes in a society. Coping up with

the taste of time or in other words, upgrading with the evolution process of

civilization; if the music succeeds to adapt the necessary changes without

damaging the core, becomes enduring. Unlocking the music into various

dimensions as per the taste of time, may bring it a transient achievement for a

certain period but the music loses its perspective very quickly and becomes out

of fashion. With the rapid movement of time and transition in society, if the

music unable to pace up hand to hand, slowly that music goes into oblivion.

3. TRANSITION VS DISTORTION

1)

Distortion

of Music and its Form

2)

Distortion

of Music Instrument and its Sound

3)

Distortion

in Scholastic works

3.1. Distortion of Music and its Form

1)

Stage Music:

Music making by adapting a framework that is conducive to the proscenium stage

is trendy in the cultural scenario. It has both pros and cons. The advantage of

this is that it is evolving to a revised form and is able to create a space in

pan Indian cultural mode. It promotes musicians from any background or class to

participate in it. In contrast, the proscenium framework is not that conducive

to accommodate all kinds of music making that takes place in traditional Ganda

Baja drumming.

2)

Music formation:

In the current times, the search for ‘creativity’ is causing the music to lose

its finesse. For example, using forty Lisan

drums in a program may bring attention but definitely fails to produce good

music.

3)

Music making process: Hanging the instruments on the body and dancing along is aesthetically different

from keeping the instruments on stands. Tying the Lisan

on the waist and playing is the traditional practice that allows bodily

movement of different expressions. When the feet move with Chap (Ghunguru), the experience for the audience is

grounded in cultural foundation. Not all musicians are qualified to do this.

Tying the Chap on legs adds a flavour of aesthetics to sound and

movement of rhythm. Unfortunately, in the current times, the later practice is considered

as a high status one and the former one, a low status practised by traditional

lower stratum musicians.

“Of the

various aspects of a ‘living’ culture, music is most likely to be the last to

accept change. In fact, due to the inherent connection’s music has with various

life – areas, changes which may be treated as indicators of developments at

deeper levels of the societal psyche.” Ranade

(1992)

One of the

major impacts that stage music - Dulduli has

had is that it has helped overcome the issue of social stigma, where a

non-hereditary musician from a higher class can also play the instrument tied

to his waist or hanging from the shoulder and yet it has respect in society. However,

in street procession music - ‘melody band party’; it has been seen that if the

musician is non-hereditary and from an upper class, he will not opt to hold the

drum on the body and play. What music you play and what way you play also

define someone’s social status and dignity. Also, it affects the music it

produces. These are very subtle aspects that shape music, culture, and social

psyche.

3.2. Distortion of Music Instruments and its Sound

1)

Modification

of sound through audio engineering may sound trendy. But the fact is that the

instrument doesn’t find its own voice, meaning the timbre.

2)

Use

of synthetic membrane may be less burdensome from a maintenance point of view,

but it does not produce the sound that is as soothing as traditional.

3)

Assimilating

allied and electronic instruments override the originality of an instrument in

terms of the music style it represents.

4)

Increasing

the numbers of instruments and drummers just contributes to a loud sound.

However, it is not feasible to produce all types of traditional music with

larger group of bands with proper coordination and aesthetics as well.

3.3. Distortion in Scholastic works

The

scholastic works undertaken from time to time by various scholars have also

caused many distortions and this has not yet been addressed with proper

rationale. One of the major distortions here is, the connotations of

terminologies that have been continuously changing. For instance, the earlier

works have very poorly addressed Ganda Baja and have portrayed Ganda in

a rather bad light. The study on Ganda Baja tradition by Dr. Lidia Guzy (German Anthropologist) brought a whole new

perspective on music culture which was never present before.

1)

Data

that is obtained through secondary resources sometimes may fail to give the

factual information. The narration or description comes as per the viewpoint of

the informant or the researcher’s in-depth field study. The colonial narratives

and their worldview reflect the same.

The Tribes

and Castes of Central Provinces of India, Vol – III by Russel R.V. and Hiralal, Rai Bhadur describes the

‘Ganda’ and ‘Ganda Baja’ that fail to see the sacred values that Ganda

Baja has. That work depicts the then connotation of Ganda Baja in

1916 is totally different from the present scholastic approach and perspective.

Russell

and Hiralal (1916)

2)

Use

of terminology sometimes confronts social issue. To avoid that it is sometimes

replaced with acceptable terminology. Sometimes we find scholars using the term

‘Dulduli’ instead of ‘Ganda Baja’.

Just as an

example, in the thesis, “Tribal and Traditional Folk Dances of Odisha” by

Jayanta Kumar Behera we can see the term ‘Dulduli’

in the context of Sing Baja and Sing khel.

He may have his own reasons for not using the term ‘Ganda Baja’.

“The folk

dance Singbaja or Singkhel

is also otherwise known as Dulduli. It is a

community based professional dance being danced by the schedule caste people of

western Odisha in almost all the districts with a little variation.” Behera

(2016)

Changing

the nomenclature from ‘Ganda Baja’ into ‘Dulduli’

has resulted in degenerative impacts.

“First, it

is fading out the Ganda into oblivion. Also, it is causing the Ganda to

move towards Dulduli. Secondly, the word ‘Dulduli’ is just a decade old name whereas ‘Ganda

Baja’ is centuries old, putting a limitation to the musicological history

of centuries old tradition. Thirdly, the ‘genetic’ factor has a great impact on

the authenticity of this traditional music. The revised music causes decay in

its performance, practically. The depth of drum-stroke, or the holding position

of the drums or the recitation of drum language of Ganda Baja, still to

be learnt from the traditional performers.” Prajapati (2018)

4. OBSERVATION

Today, the

folk music of western-Odisha is witnessing a paradigm shift at every nook. As

per the societal change and its impact on common life, gradually the music is

changing its cultural context to current cultural demands.

The music

practice and the traditional repertoire is shifting to a new mode (towards

proscenium stage) where the traditional way of making music hardly finds a

space for it to present itself according to its natural shape and the

traditional musicians found to be unfit. Hence, remain marginalized. Only dance

oriented music find a space in stage and other kinds of music are excluded. As

a result of which, the music repertoire or knowledge of centuries is gradually

decaying in its value and authenticity.

The

traditional performance practice is unable to meet the current trend of

cultural demands. The traditional performer is bestowed with the explicit

knowledge and information on his respective subject or can say repertoire, but

the music is losing its socio-cultural relevance in its practice and decaying

rapidly. On the other hand, the performer of current trend who does not

necessarily belong to a hereditary or traditional background is though able to

manage a platform for his music; unable to compensate for the lack of in-depth

knowledge on the authenticity of that particular music subject.

It is the

social background and their lack of information, up gradation and awareness to

current cultural happenings, the traditional musicians remain marginalized. To

expose them to the cultural platforms, it needs a mediator to connect the

musicians with facilities and platforms those are far reach from them. It’s a

big question mark to fulfil these need and way out a solution to their

constraints of economic harsh and social dignity.

On the

other hand, the upcoming generation of traditional musicians either moving

towards Dulduli or leaving Ganda Baja

and searching for other professions. In few cases, if the son of a drummer gets

into a job, Ganda Baja becomes a taboo for him and the tradition that

was continuing from forefathers ends there.

There has

been a huge concern over the decades by the elites, cultural organisations, and

government to revive the art forms and save it from damage. These noble

endeavours result in folk music getting accepted and practised by people from

different classes and sectors. There is a stupendous focus on the revival of

western-Odisha folk music by means of study, practice, documentation,

preservation, communication, and appreciation. The elite class embracing music

as a subject in the form of revised music. However, unable to master it like a

traditional one.

According

to the changing mode of current practice of western-Odisha folk music, it is

redirecting itself into a cross-cultural and interdisciplinary platform,

finding a new space in academic or classroom or curricular mode of music

practice. The music is now not confined to traditional performance practice

aspects but rapidly moving towards stage performance-oriented music platforms.

The Dalkhai (the festival of dance during Dusserah) is no longer seen in the streets but on

the proscenium or in social media platforms. Similarly, there is a significant

growth of non-hereditary musicians who do music on cultural platforms, but not

in socio-cultural life.

Today, a Dalkhai song need not be sung on the occasion of Dusserah alone but can be sung on any occasion. It

can be taught to someone in a classroom, or a research work can be carried out

on it. The treatment of music can be that of traditional practice or stage

performance or teaching or cross-cultural experimentation or research-oriented

work or so.

The

dissemination of music knowledge is changing its form from ‘Learning it by

doing’ to ‘Learning it through academic curricular discipline’. The government

schemes like Junior/Senior Fellowships, CCCRT Scholarships, Guru-Shishya

Parampara Grants by Zonal Cultural Centre and many facilities are encouraged

highly for learning folk music. This contemporary way of learning folk music

demands that a teacher and student necessarily follow an academic methodology,

which otherwise wasn't present in the past tradition of learning through seeing

and practice. Thereby, the traditional musician remains unfit in account

of his educational qualification account.

5. CONCLUSION

(PROPOSED SOLUTIONS AND ROAD AHEAD)

From the

observation, it is obvious that, it’s a crucial period of transition for the

western-Odisha folk music, where the traditionally practised music has

drastically unlocked to various dimensions and is taking different shapes

leaving behind the core. Given below are proposed action items that could be

taken up at various levels to further the cause of traditional Ganda Baja.

1)

Creating

better scopes/platforms for traditional music forms to showcase at National and

International events – Role of Govt, Role of Local Communities, Role of

Cultural Organizations.

2)

Developing

Academic Curriculum – Codifying a conceptual framework that befits traditional Ganda

Baja to develop pedagogy for current way of disseminating music knowledge.

3)

Role

of school and university in curriculum development, music as a subject –

including Ganda Baja in extracurricular activity.

In this

present crisis, the folk music of western-Odisha needs an urge to bridge

between the existing tradition and on-going transition. The framework of traditional music practice

has to be linked with the revised music performed in the stage by the non-hereditary

musicians. Simultaneously, modes of disseminating music knowledge from the

traditional one with the class-room mode of present-day pedagogical methods

should be well studied and codified. That can only be possible by paying an

equal amount of importance to the core traditional musicians and their music.

The Ganda

Baja should be recognized by its own nomenclature. If Ganda Baja is

replaced by Dulduli, then we are definitely

losing the core music. The traditional Ganda Baja in its core form would

be a great resource for future generation of musicians to explore, expand and

further it. To make it happen, there is an utter surge to demarcate the Ganda

Baja as well as the musicians from Dulduli

through a proper field study.

It invites

a discussion from different agencies to arrive at a strategy that how to

suffice the needs of the traditional musicians and bring dignity to their music

or in other words, accommodating Ganda Baja and the musicians as a

beneficiary in various platforms. That might make an inroad for traditional Ganda

Baja.

Academic

collaboration with the traditional music would be a part of solution. Rather

than just classroom techniques of teaching the music curriculum as a study, if

practical performance mode is adopted to come out as a performer, the

traditional musicians would get a platform to showcase their art and earn their

bread. Simultaneously, the students of music would derive the benefit of

experiencing the first-hand information of authentic music and would come out

as a performer but not just earning a degree. Likewise, the music can be

introduced to students in school levels and making them capable of performing

the music at least in a level of what we find in a school march-past band.

Above the

all, there is a dearth of literature especially on Ganda Baja music. In

the early works Ganda Baja is least mentioned and never described in detail

as it is supposed to be. As a participant observer of this music culture and

student of music, I strongly realize that this western Odisha folk music

culture has enough to contribute to the world of folk music research as well as

contemporary folk music till the core form of music is alive. In depth study on

this music and the musicians is yet lacking.

I hope, the

issues addressed in this study will open up new avenues for future works on

various aspects of Ganda Baja. Especially, scholastic studies in terms

of socio-cultural problems and the socio-economic constraints of traditional

musicians, the cultural-politics and scopes for the music making possibilities

in its revised form, experimentation of music with current technology and so

on.

In the other hand, to take this music into a new horizon it needs the musicians of creative minds with having the thorough knowledge and experience of the core music as well as understanding of current music in terms of grammar, styles, technics, technology and so on. The sub-forms of the main music stream will find more possibilities to explore and will expand to the maximum if the root music is taken care well. I have my own limitation to address and justify each aspect of this study. Still this study has to be furthered to answer the question – How to blend the music of traditional musician with the current transitional development without causing any distortion.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Behera, J. (2016). Tribal and Traditional Folk Dances of Odisha. Centre for Cultural Resources and Training.

George, G. M. (2015). The Duma Among The Gandas of Western Odisha : A Socio- Anthropological study. Tata Institute of Social sciences. Retrieved on 24 April 2022.

Guzy, L. (2013). Ritual Village Music and Marginalised Musicians of Western Orissa/Odisha, India. International journal of Asia pacific studies, 9 (1), 121– 140. Retrieved on 20 May 2022.

Guzy, L. (2022). Dulduli : the Music ‘Which Touches Your Heart’ and the Re-Enactment of Culture. In press in : Georg Berkemer, Hermann Kulke (ed.), Centres out There ? Facets of Subregioanl Identities. Delhi : Manohar. Retrieved on 10 May 2022.

Prajapati, D. (2018). Ganda Bajaa : An Ethnical Folk Music Form, a Separate Entity. Meru. Sambalpur.

Ranade, A. D. (1992). Indology and Ethnomusicology : Contours of the Indo-British Relationship. New Delhi : Promilla & Co. Publishers.

Russell, R. V. & Hiralal, R. B. (1916). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Vol. III. London : Macmillan and Co., Limited St. Martin’s Street. Retrieved on 15 April 2022.

Senapati, N. (1971). Orissa District Gazetteer. Sambalpur. Retrieved on 04 August 2022.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2022. All Rights Reserved.