ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing ArtsISSN (Online): 2582-7472

|

|

VIRTUOSITY OF RAJA RAVI VARMA AND SHYAM BENEGAL’S BHUMIKA – A VISUAL RELATION

Rishabh Kumar 1 ![]()

![]() ,

Anketa Kumar 2

,

Anketa Kumar 2![]()

![]()

1 Assistant

Professor, National Institute of Fashion Technology, Gandhinagar, (Gujarat),

India

2 Assistant

Professor, National Institute of Fashion Technology, Raebareli, (Uttar Pradesh),

India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

Aside from

providing amusement and beauty, art and film have always served as a

reflection of society and culture. Both the arts and film have had an impact

on society. The works produced in both mediums have received recognition and

acclaim on a global scale. Artists draw inspiration from the world around

them to produce works of art. In his classical paintings, the well-known

artist Raja Ravi Varma addressed "Art" and "Life"

aesthetically by blending true Indian mythological sense with European

Academic Art. Indian Modern Art Movement can be traced back to the

exploration in Varma's works of art. Similar to

this, film directors try to depict place, time, and common practices using

their actors. This analysis of Bhumika[1] (Role), a feature film by Benegal, aims

to give a broad overview of the film's formal components as they symbolise the avant-garde ideal of balancing

"Art" and "Life." The essay is an analytical attempt to

look at art and life in relation to Raja Ravi Varma's artworks and the female

character in the film Bhumika. |

|||

|

Received 15 September 2022 Accepted 21 October 2022 Published 17 November 2022 Corresponding Author Rishabh

Kumar, rishabh.kumar1@nift.ac.in DOI 10.29121/shodhkosh.v3.i2.2022.192 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2022 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Costumes, Bhumika, Raja Ravi Varma, Shyam Benegal |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Raja Ravi Varma the renowned Indian artist used the

European academic art movement in India with real Indian mythical sensibility

to address societal significance aesthetically in his classical paintings. He

started the Indian Modern Art Movement at the beginning of the nineteenth

century. One of the best painters in Indian art history, Ravi Varma was an

Indian painter and artist who was born in Kilimnoor

to an aristocratic Travancore family. He is renowned for his incredible

paintings, many of which are inspired by classic Indian epics like the

Mahabharata and the Ramayana. In many ways, Indian culture, religion, and

tradition are greatly influenced by the two great epics, the Ramayana, and the

Mahabharata. Sengupta

(2011) contends that these

epic tales are transmitted to future generations not through books but rather

through the traditions and cultural milieux in which one is born. He adds that

neither of the two epics is regarded as the inspired word of God. But just as

the Bible and Greek mythology must historically represent Westerners, these

tremendous traditions function as pure denotations for Hindus. One of the few

painters, Ravi Varma, was able to successfully combine Indian culture with

academic painting methods. He is regarded as one of the most well-known Indian

artists in part because of this. With

his flawless oleograph and lithograph methods, Varma is also credited with

popularising Indian style and household posters throughout the world. His

depictions of Hindu deities eventually inspired many people from lower classes

to worship these deities. These people were frequently prohibited from

accessing temples during that time, so they brought these reasonably priced

prints of gods into their homes to worship. All people adored the beauty of

South Indian women, which Varma's paintings emphasised. By portraying ladies

with their emotions and wearing modest interpretations of Indian clothing, most

notably the saree and its embellishments, he unmistakably caught the melancholy

of Indian culture.

With around sixteen different

Indian languages, including English, and across its States and Union

Territories, India is the largest film producer in the world. Let's first grasp

the history of cinema in India and examine the forerunners of cinema before we

attempt to analyse the movie in question. Modern Indian Theatre began when a

theatre was built in Belgachia, a region in north

Kolkata, during the time that cinema first appeared in India, about 1825. At

the time, it was under British colonial rule Deshpandé et al. (1993). One of the first Bengali dramas created and performed at this time was

Buro Shalikher Ghaare Roa (1860) by Michael

Madhusudan Dutt. At the same time, Girish Chandra's

performance of Dinabandhu Mitra's play Nil Darpan

(1858–1859) at the national theatre in Kolkata sparked both praise and

criticism for portraying the misery and tragedy of indigo growing in rural

Bengal and playing a significant role in the indigo uprising. Despite being

ruthlessly put down, the indigo farmers' uprising had a profound effect on the

government, which created the Indigo Commission in 1860. Yarrow

(2001).

The Lumière brothers' short

films, which had their premiere on December 28, 1895, in Paris, were a

breakthrough in the use of projected images for both entertainment and

communication, giving rise to a new kind of media known as cinematographic

motion pictures. Though there had been earlier cinematic successes and

showings, neither their calibre nor their momentum matched the Cinématographe Lumière's ascent

to fame Gokulsing and Dissanayake (2004). Soon after, film production companies popped up all over the world.

During the first ten years of the motion picture industry, film went from being

a novelty to becoming a well-established mass entertainment industry. The

original motion pictures had no sound and were in black and white and lasted

less than a minute Khanna (2003). The first professionally produced feature film, Raja

Harishchandra was released in 1913. The film was created by Dhundiraj Govind Phalke (1870–1944), known as the

"Father of Indian Cinema" Bose

(2008). Phalke watched the English movie "Life of Christ," which

inspired him to start visualising images of Indian gods and goddesses. He was

obsessed by the desire to see Indian imagery on the big screen in a wholly

Swadeshi endeavour.

The British government, which was dominating India at the time of World War II, used cinema as a medium to spread war propaganda for a brief period in 1939. They established a film advisory council in Mumbai and ordered a few movies, including Khwaja Ahmed Abbas' Dharti Ke Lal (soils of the Son) Srivastava (2017). Neecha Nagar (The Lower City) won the "Best Human Document" prize at the 1948 Cannes Film Festival, while Doctor Kotnis ki Amar Kahani and Dharti Ke Lal were also well-liked movies. The majority of Indian films made in 1947 represented hope, romance, great aspiration, values, freedom, and the victory of the liberation fight Agarwal (2014). New social issues were attempted in movies like Samaj ko Badal dalo (Change the society) by Vijay Bhatt, Sindoor (about widow remarriage) by Kishore Sahu, Shaheed (The Martyr) by Ramesh Saigal, Hum Bhi Insaan Hai (We are also humans) by Phani Majumdar, and many others. The modern Indian cinema industry started to take shape about 1947. During this time, the movie industry had a tremendous and unprecedented development. Famous filmmakers like Satyajit Ray and Bimal Roy made movies about the daily difficulties and survival of the lower caste Singh and Pandey (2020). Films with social messages started to take centre stage while historical and mythological subjects started to fade away. Prostitution, dowry, polygamy, and other social problems that were prevalent at the time were topics covered in these movies. Most movies had mastered the melodrama style by this point. At this point, music was a necessary element of the typical Indian movie Dwyer and Patel (2002).

Characters appear in movies dressed appropriately and surrounded by the suitable environment. However, there is a clear mystery at the heart of the historical ensemble concept since it might not be possible to carefully replicate earlier styles, shapes, and textures. (2002) Street The audience's comprehension that the movie is historically accurate doesn't depend on any particular knowledge of the past; rather, it comes from recognising obvious clues and visual depictions of things that are thought to be plausible. The most shocking examples of this peculiarity are renderings of famous historical persons wearing clothes, when it is crucial to include certain crucial signals to convince the audience that it is the life and seasons of this particular character that are being shown Edensor (2016).

The ethos and ideologies of every civilization at any given moment have always been reflected in cinema. The personalities became the most important medium, but other elements such as clothing, music, and opulent objects were also used to emphasise this reflection. The characters' worldview, way of thinking, concerns, or prejudices were the same as those of the general public Hayward (2002). Through clothing elements that can serve as symbols, film costumes create their implications. As a result, the costumes seen in the movie can also be viewed in a semiotic context. The Semiotician's job in the Saussurean method is to look past the specific elements of clothing, such as tone, texture, surface, lines, and motifs. Semiotics can be used to anything that should be perceived as suggesting anything, in general, to everything that has importance within a society. In fact, one can use semiotic analysis to any dramatic art and trade, including dancing, make-up, clothing, and scene planning, even within the context of theatrical expressions. Semiotics examines everything that denotes a distinct meaning from what we typically refer to as clothing signs. Signs in costumes can be seen as colours, symbols, graphics, fabrics, and types of clothing and adornments Berger et al. (1972).

The quirky or new wave-inspired films made in India in a

variety of genres have received praise and recognition on a national and

international level. Shyam Benegal

is an Indian film director, screenwriter, and documentary filmmaker who was

born in Hyderabad on December 14, 1934. He is among other notable directors. He

is frequently hailed as the father of parallel cinema and is regarded as one of

the greatest directors of the post-1970s era. He has won numerous honours,

including a Filmfare Award, a Nandi Award, and 18 National Film Awards. He

received the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, India's top

honour in the art of cinema, in 2005. He received the Padma Shri, the

fourth-highest civilian honour bestowed by the Indian government, in 1976, and

the Padma Bhushan, the third-highest civilian honour, in 1991 for his services

to the arts. In 1962, he produced Gher

Betha Ganga (Ganges at the Doorstep), his first Gujarati documentary movie.

Ankur (1973), Nishant (1975), Manthan (1976), and Bhumika

(1977), Benegal's first four full-length movies,

established him as a pioneer of the era's new wave film trend. The Muslim women

Trilogy is made up of Benegal's films Mammo (1994), Sardari

Begum (1996), and Zubeidaa (2001), all of

which were nominated for National Film Awards for Best Feature Film. The

National Film Award for Best Feature Film went to Benegal

for seven times. He was also awarded the V. Shantaram

Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018.

Shyam Benegal’s 1977 Indian Hindi film Bhumika is one of his works. Smita Patil, Amol Palekar, Anant Nag, Naseeruddin Shah, and Amrish Puri are the movie's stars. While all of Bhumika's formal elements, including sound, music, off-screen space, and poetic monologues, cannot be discussed in this research, two key elements—costume and non-diegetic shots—are isolated for consideration. Additionally demonstrating a similar methodology to Varma's work the intellectual underpinning of this goal, namely the reconciliation of the individual and society, is also presented in the women-focused film Bhumika. As a result, the term "Life" describes how non-diegetic montages act as clues and traces from a world or civilization that does not fall under the creative purview of the diegesis.

The autobiography of Marathi and

Hindi film legend Hansa Wadkar from the 1940s served

as the inspiration for Bhumika. According to author Hansa, the book's title,

loosely translated as "Listen, and I'll Tell," was taken from his

1959 mega-hit musical film Sangte Aika Wadkar (2014). As stated in her biography, she began appearing in live musical

productions as a young actress in order to primarily

support her mother and grandmother. This scenario is transformed into a

human-interest drama in the film, which follows a traditional courtesan as she

struggles to understand modern mass culture and develop her own unique

identity. The introductory story has Usha, the

movie star, fleeing her husband and eventually finding refuge in the

restrictive limits of Kale's estate's feudal landlord, first with her male

co-star Rajan. Her husband and the police show up to

save her from Kale. Now that she is free, she refuses the support from her

husband, her now-married, adult daughter, whose modernism breaks with the

matrilineal tradition, and her ex-lover Rajan,

apparently in favour of the freedom that she yearned for Vasudev (1986).

2. UNCONVENTIONAL

PROTAGONIST

Women seeking to become independent through various social

relationships, failing, and then “going away” have been discussed frequently.

The films of the time, including Indian cinema, commonly included a common and

well-known cliché. The feminist critic Susie Tharu's

criticism of Usha's counterpart Sulabha in Jabbar

Patel's Umbartha (The Threshold, 1981), who

was also portrayed by Smita Patil, is eloquent

evidence of the stereotype in Bhumika: “The film establishes her as the central

character as well as the problem (the disruption, the enigma) the film will

explore and resolve... it is clear that to search herself is, for a woman She

will fail, but she can do so in a heroic and wonderful way in her endeavour”. (Third

World Women's Cinema, Economic and Political Weekly, Bombay, 17 May

1986).

The early modernist painter Raja Ravi Varma, on the other hand, favoured

Indian men and women in his works by using a range of media. The definitions of

"artist" and "Indian artist" have undergone a significant

change because to Raja Ravi Varma, the first and only Indian artist from

British India (1848-1906). Due to a number of creative

and more fundamentally societal aspects, he is recognised as one of the

greatest painters in Indian art history. First of all,

his works are recognised as some of the best examples of the fusion of wholly

Indian sensibilities with European technology. His

paintings preserved the tradition and elegance of Indian art while

incorporating the most current European academic art techniques of the era.

Second, he is renowned for selling oleographs of his paintings at a fair price

to the general public as approachable popular art. A

near relative of the Travancore royal family in the Indian state of Kerala,

Varma emerged as a synthesis of tradition and modernity, a pioneer of

modernism. Eventually, this led to the creation of an entirely new genre of

mythological oil paintings Neumayer et al. (2003).

3. BHUMIKA (THE ROLE)

In addition to being a common

household idol, Ravi Varma's depiction of Gods and Goddesses also flourished in

mythological film and television. His storytelling was too prevalent to be

avoided even in mainstream social cinema. In films like Satyam Shivam Sundaram and Ram Teri Ganga Maili, the film directors have been motivated by the

Raja's legacy of the wet saris he painted on his ladies in numerous paintings.

Women are personified in Raja Ravi Varma's paintings as described by Nirupama Dutt, including Meena

Kumari in Guru Dutt’s Sahib, Bibi Aur Ghulam,

and the courtesan Smita in Shyam

Benegal’s Bhumika.

3.1. THE WIFE AND LOVER

The film Bhumika builds its enigmatic lead character with a heavy undertone of nostalgia through a series of sepia flashbacks showing Usha's upbringing in the Konkan, a western region of India. These flashbacks show Bhumika's contacts with Dalve, who will become her husband in return for helping her struggling family. This is without a doubt Bhumika's most attractive quality. Usha is depicted in the black and white photo wearing traditional Indian clothing for females, including a long skirt that reaches her ankles and a top with puffy sleeves Jain (2003). In other memories, her husband is portrayed as a crafty opportunist who takes over of her professional life. Amol Palekar, who plays Dalve, can be seen wearing a kurta and a topi on his head and baggy pyjamas.

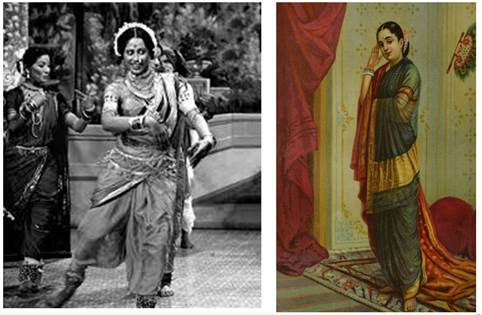

Figure 1

|

Figure 1 a Davle’s love Interest Usha. Image (right), b

Arjuna and Subhadra (1890) 35x50cm, Oleograph, Raja Ravi Varma. Collection:

Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation, Bengaluru Source https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/arjuna-subhadra-ravi-varma-press/FQE8WSwyZcs-yA?hl=en |

Arjuna travels to Dwaraka to be with Lord Krishna while he is in the middle

of a self-imposed exile for breaking the terms of the agreement over spending

time with Draupadi and his four siblings. Arjuna was eager to wed Subhadra when

he initially fell in love with the Lord's stunning sister. Arjuna kidnaps

Subhadra and then weds her after pretending to be a recluse. Subhadra is seen

in the picture beaming, wearing a red sari with a gold border, and being

delightfully chubby. Her nose ring sparkles seductively, and her hair is covered

with beautiful diamond adornments. She is eschewing Arjun's attempts to push

her into his path. Before turning attention to the background and realising

what is being recounted in the background as well in stunning and deeply

textured works, it is approvingly regarded to be a classic oleograph of Raja

Ravi Varma.

3.2. THE COURT DANCER WITH ELEGENCE

Figure 2

|

Figure 2 a Usha the Court Dancer, b Vasantasena, Oleograph on Paper (1896) Raja Ravi Varma, Collection National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi |

Vasantasena is one of the most well-known characters in Indian

classical theatre. This unique story of love, grief, and desire features

accurate depictions of the characters from Sudraka’s Mrichchakatika. The playwright departs from the traditional

methods used by Indian dramatists. She does not fit the stereotypes of what it

means to be a mother, a wife, or a daughter. She is a unique paradox. She is

both a coveted commodity and a self-sufficient person who values each individual's right to self-determination. She has

economic influence, which is significantly different from the traditional roles

that women had at the time in theatre. Despite this, she lacks social rights

because she is a courtesan. Ironically, she does not have access to the perks

enjoyed by married women who lack any sense of independence, despite

the fact that she is not dependent on money. However, Vasantasena is an admirable figure since she defies society

without a fight.

When it comes to partnerships, Vasantasena makes the decisions and assumes the initiative.

The classic Sanskrit drama nayika are frequently observed to be devoted to

their loves or husbands to the point of religion. The person who is often

regarded as the leader is the nayaka. Sudraka's Vasantasena can tell the difference between adoration and

love. She understands the difference between true love and politeness in the

workplace. She epitomises desire, wit, and every other trait that a modern city

lady aspires to possess. She is a unique person with a unique personality. Not

just because of her physical attraction to him, she loves Charudatta

for his goodness and sincerity. She showed compassion and charity by freeing Madanika so that she might marry Sarvilaka,

and bravery by persevering in the face of a formidable foe like Samsthanak. She doesn't lack maternal instincts, is

disloyal, or is submissive. As a result, Vasantasena

is a spherical character.

In Bhumika, this process of

rewriting history in order to create a tragic

narrative idiom is presented in black and white. Smita

Patil's female lead character has the opportunity to

explore the wonders of an indigenous popular culture thanks to the plot in

particular. The way Usha edits the images of her partners, and her clothing

beautifully conveys her suffering. As a result, the character's portrayal

through the clothing helps to show how the woman's conscience compels her to

respect social norms while also torturing the woman locked in the role of wife

to be required to play the conventional role as required by Indian society. One

of the key influences on Marathi and Gujarati theatrical costumes has been

identified as Raja Ravi Varma, the well-known female impersonators of the early

20th century. During the movie's opening song, Smita

Patil performs on stage while wearing a stunning sari, numerous layers of

makeup, and a nose ring. The dancing performance comes to a finish, and Usha

promptly changes into her everyday attire. It is highly likely that after the

scene, someone will notice that the woman is an actress, the wife of a man who

is far older than she is, and the mother of a teenage girl.

The scenario from 25 years

earlier where an eight or ten-year-old girl is trying to save the chicken from

her own mother and no one else is then flashed back in the narrative. Following

that, the story keeps emphasising Usha's romantic interest in Anant Nag. Given

the girl's close bond with the chicken and the mother stealing it to prepare

food for the visitors, it seems like a bizarre sight. This episode makes

references to Usha's constant efforts to protect herself from other people in

the film. She fights with everyone who cares for them or is otherwise involved

in their lives in this endeavour Bhattacharjee and Thomas (2013). One could say that when we were making the movie, we saw the two

genres of "fringe ruralist realism" and

"creating the fictions of a collective "past" as complementary

methods for addressing the same issue: achieving an authentically indigenous

feel for a viewership that wouldn't want to engage with the dominant

mass-entertainment modes of India's film industry. As a result of how it

broadened the range of issues in New Indian Cinema and subsequently allowed for

a longer interaction with the mainstream cultural vernacular itself, this is

without a doubt the area where Bhumika has had the most impact.

The ladies were prohibited from getting married since their occupation

or employment was very visible, in accordance with caste customs. The

musicians, dancers, and singers were locals. They had to often interact with a

male audience in order to succeed at their caste job.

In their circumstance, the customs of virginity, marriage, etc. were no longer

applicable. Although only in brief partnerships with various men who

occasionally provided them gifts, the women of this caste did indulge in sexual

behaviour. Being a man's mistress was just a little part of their lives

compared to their public profession of art, even though they shared their

religion, belonged to a Hindu caste system, and observed several other cultural

norms.

Michelle Barrett explains how representational methods are given equal weight in the process of cultural production in a clear and understandable manner. She addresses, for instance, how diverse modes of representation are impacted by genres, standards, the presence of conventional forms of communication, and other factors. We are now introduced to the disturbing and contentious "realistic" reality. Though it may be imperfect, Bhoomika's shape is simple to fit inside a broadly realist framework. However, despite all of this work, it is a complete failure. The most ardent advocate of realism, Lukacs, claims that genuine great realism shows society and people as a whole, rather than emphasising only one or the other of their characteristics. This standard shows how artistic movements that are either extraverted or solely introspective deteriorate and distort reality in similar ways. Thus, three-dimensionality, an all-inclusive characteristic that is endowed with diverse human interactions and characters from real life, is defined as realism.

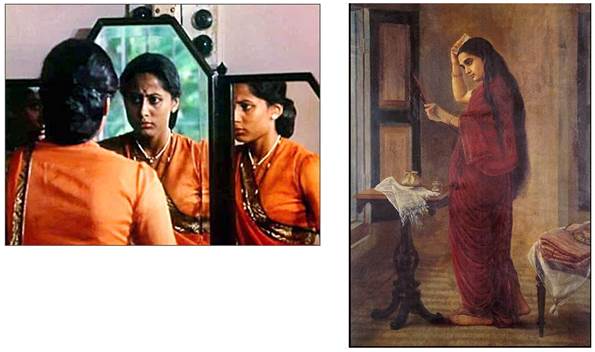

3.3. THE BEAUTY WITH COURAGE

|

Figure 3 a Usha’s Anguish,

b The Lady with a Mirror (1894) Raja Ravi Varma Source https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Raja_Ravi_Varma,_The_Lady_with_a_Mirror_%281894%29.jpg |

Despite what his critics claim,

Raja Ravi Varma's female characters are challenging to woo. His art and their

allure continue. From our puja rooms to the Ramlila grounds, from the large

screen to the little screen, from ad labels to holiday greeting cards, they can

be seen everywhere Thakurta and Thakurta (1986). Through the use of carefully chosen settings

and costumes, shot compositions, and specialised methods utilised primarily to

drive the plot, such as paintings emoting expressions of various ladies, the

division between Usha's private and public lives is skilfully conveyed. The

filmmaker, for instance, employs the picture of Smita

scrutinising herself in the mirror precisely seven times as a tool to either

reflect on her past or find inspiration for her future actions. Benegal wants to demonstrate how Smita's

response and decision to leave the house after the conflict are results of her

inner strength and progress, therefore the mirror look is crucial at this particular time. She is acting in such a risky way because

that is who she is, and the only way she can recognise and comprehend her

predicament is by staring in the mirror.

The employment of comparable visuals throughout the rest of the movie implies that it was intentional. This uses similar imagery to the artwork "Lady with the Mirror" by Raja Ravi Verma. In a flashback, Smita is back in front of the mirror after her marriage to Amol, but this time before she accuses him of using her mother and grandmother as justification for convincing her to keep making movies Sachdeva (2019). She leaves her home and is subsequently observed gazing at her image in a hotel room mirror. Benegal transitions to some of her movie clips from this image. Looking in the mirror has a new significance at this time as she considers her acting roles in various movies where the most orthodox traditions of the Indian social elite are venerated as the best qualities a woman can have Dasgupta and Datta (2018). She is reminded once more of the tension and contrast between her deeds in real life and the characters she portrays in movies after seeing a reflection of herself. Smita and co-star Rajan argue in another scene. After seeing herself, she attacks him once more in the mirror. Even when she is emotionally attached to Naseeruddin Shah and feels like killing herself, she swallows the pills while facing the mirror. Here, Benegal’s choice to take the pills is amply shown to be a brave deed; as a result, her effort necessitates further thought on her side. Benegal uses this strategy once again toward the end of the film.

Smita saw Amol and the cops pulling up to the house of the landlord Amrish. She is aware that eventually she will have to depart from the family. She approaches the dressing table and pulls a chair up to the mirror. She gives herself another once-over before beginning to remove all the jewellery Amrish had given her. This deliberate act serves as a symbol of her total rejection of him. The relationship between the individual and society is distorted as a result of this deliberate usage of a specific type of imagery, which appears seven times in the movie. Benegal’s mirror sequences initially appear to be an expression of self-reflection from a variety of life viewpoints Rajadhyaksha and Willemen (2014).

4. THE PORTRAYAL

One of the founders of modern Indian painting is Raja Ravi Verma. His works on Indian subjects were produced using western techniques, and he typically portrayed beautiful women with seductive characteristics. Since they are both creations of modern India, both artists have made significant contributions to the drive for art revival. In order to investigate the significance of gender in connection to painted space, Raja Ravi Verma's case and Shyam Benegal's portrayal of a lady in his film Bhumika have been contrasted. The female characters played by Smita Patil, and Raja Ravi Varma are likened to Usha, who was portrayed by Smita Patil in Bhumika, in their respective places. Both the setting of the artist's painting and the character in the film adopt a gender-inclined strategy that incorporates concepts of the masculine and feminine. Some eminent art critics claim that locations' relevance is mostly reliant on theoretical perception.

Self-reflection, or the capacity to occasionally subject one's own opinions to a process of critical questioning, is a prerequisite for any critical action. Benegal, however, ignores the crucial aspect that self-reflection takes place within the confines of a social environment, a world that shrinks more and more throughout the course of the film. Benegal uses the news pieces just to move the movie's chronologically, to only provide the backdrop to the narrative in the foreground, rather than relating Hansa's experiences to the social environment and setting of the time. In many ways, Hansa's life story depends on how Smita and Amrish Puri are portrayed. Benegal seeks to criticise Amrish, a wealthy landowner who is also a brahmin, in this passage because of his caste background. Corm Kaplan presents this idea fairly powerfully in her book, Culture and Feminism: In that envisaged society, all other social structural connections disintegrate and disappear, leaving us with the simple drama of sexual difference as the only scenario that matters. Mass market romance frequently portrays sexual diversity as inherent and unchangeable, pairing an equally “given” universal masculinity with a constant, transhistorical femininity.

5. ANALYSIS

Ravi Varma is

widely renowned for his paintings of seductively looking at the viewer,

lovelorn women. His sketchbooks are filled with various examples of women in

everyday circumstances, so it is clear that he

experimented with the subject, but relatively few of these sketches seem to

have developed into final works. Some of the paintings aren't strictly

portraits because it's unknown who commissioned them, no identifiable ladies

are depicted in them, and they instead show people in situations rather than

just as individuals. In his academic paintings, Ravi Varma attempts to move

beyond the prevailing paradigms of anthropological portraiture or studio

portraits of the time in order to explore the subjective

potential of the Indian woman in her own world. This characterization is

explored with great empathy and sensitivity and sheds light on the idealised

female self in the turn of the century Dinkar (2014).

Usha regularly seen dancing in Bhumika while wearing a red

brocade top over a light olive-green sari with a golden border draped in

Marathi style. Her hairstyle, which resembles an apsara, a celestial courtesan

known for seducing Indra and his courtesans in legend, is a flower-adorned bun

with heavy jewellery on the neck and waist. By observing a number

of specific cues, the audience can interpret Bhumika's messages. The

time of day can be deduced by Usha's arrival in several sequences clad in a

white nightgown. There are references to the characters' emotional makeup,

social standing, and career background in the movie's attire. Bhumika uses

clothing among other things to illustrate the concepts of Usha's many stages in

life. Usha is dressed in a silk sari and blouse at the height of her successful

acting career, along with a mangalsutra around her neck,

representing the good money she has accumulated from her profession, while they

argue about Keshav's dependence on Usha's income. We can categorically

establish links between attire and emotional state in the scene where Usha is

shown leaving the house wearing a plain cotton sari with a floral-printed

blouse and returning wearing a maroon-colored sari

with a red bindi on her forehead, representing

a married woman in Hindu culture. This is taking into account

the emotional forlornness and desperate attitudes of Usha.

Varma's artwork has flourished for more than a century in addition to enduring. His painting “Bharatiya nari” had a profound effect on theatre, film, television, and popular art, such as posters and calendars (Nirupama Dutt, Women in Raja Ravi Verma Mould). Another instance of an emotional state and status change that is indicated through the usage of clothing is Usha moving in with Vinayak Kale, a wealthy businessman played by Amrish Puri. She is welcomed at his home by the mother, his first wife, and the boy while wearing a fitted sleeveless blouse and a beige silk sari. Then she gave a red sari and a few accessories to wear inside the house so that she would look like a decent housewife. She is seen toward the end of the film wearing a green cotton sari and finding comfort in her alone.

Hindu society forbids non-widowed women from dressing in all-white attire, hence Usha's frequent donning of cotton saris during her relationship with Vinayak Kale further emphasises her appreciation for tradition and custom. Thus, Usha's saris from this film have come to stand for her aspirations. In her sari at the beginning of the film, Usha is not wearing any dark colours. For instance, according to Brockett, the brocade she is wearing in the opening scene's light, crisp, and slightly glossy surface expresses femininity and brittleness. As the film came to a finish, she mostly wore saris in dark hues. "Materials with thick threads...have a homespun quality associated with the working class," claims Brockett.

Usha's frequent donning of cotton saris during her engagement with Vinayak Kale also serves as a representation of her love for tradition and custom because the Hindu culture forbids a woman who is not widowed from donning plain white attire. Usha's goal is thus represented by the saris she dons in this film. At the beginning of the film, Usha is dressed in a sari of a lighter hue. For instance, she is wearing brocade in the first scene, which according to Brockett conveys brittleness and femininity due to its light, crisp, and slightly glossy surface. At the conclusion of the film, she wore mostly dark-coloured saris. It represents a fraudster taking advantage of a respectable career or pretending to work in a different field. The movie's events indicate that Usha's first husband is always poor while acting and thinking like a wealthy guy. He wears slippers, a pair of basic slacks, a long shirt with the collar buttoned up, and a cap. Each of his costumes is a contradiction bundle that depicts his character, and as the film progresses, his physique shifts from the traditional middle-class Indian garments to Western trouser suits.

Figure 4

|

Figure 4 a Actress Smita Patil (Usha), b Kerala Royal Lady, Oil on Canvas, 43x61cm (reproduction), Raja Ravi Varma |

|

Figure 5 a

Kadambari, 50x35cm, Chromolithograph, (1910) Raja Ravi Varma.

Collection: Ms. Chamundeshwari PranlBhogilal,

Mumbai, Maharashtra. b Usha Practising Along with Her Grandmother. |

6. CONCLUSION

The way women are treated in patriarchal societies is exemplified by Bhumika. Relationships in this society are analysed from the perspective of men, much like Raja Ravi Varma's image with its reflections of several women. In the film Bhumika, Usha portrays a variety of characters, from the frightened wife of Davle to the romantic interest Rajan, the mistress of Sunil Verma, to the representation of a conventional Hindu wife to Vinayak Kale. His representations of Indian ladies earned such admiration that a stunning woman was usually said to appear as though she had just emerged from a Varma painting.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

Art Culture (2010, July 19). Shyam Benegal on his Love for Art. Hindustan Times.

Berger, J., Blomberg, S., Fox, C., Dibb, M., and Hollis, R. (1972). Ways of Seeing. Penguin Books.

Bhattacharjee, S., and Thomas, C. J. (2013). Society, Representation, and Textuality : The Critical Interface. SAGE Publications India.

Bose, M. (2008). Bollywood : A History. Roli Books Private.

Dasgupta, R. K., and Datta, S. (2018). 100 Essential Indian Films. Rowman & Littlefield.

Deshpandé, R., Farley, J. U., and Webster Jr, F. E. (1993). Corporate Culture, Customer Orientation, and Innovativeness in Japanese Firms : A Quadrad Analysis. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 23-37. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252055.

Dinkar, N. (2014). Private Lives and Interior Spaces : Raja Ravi Varma's Scholar Paintings. Art History, 37(3), 510-535. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.12085.

Dutt, N. (2002). Women in Raja Ravi Varma Mold.

Dwyer, R., and Patel, D. (2002). Cinema India : The Visual Culture of Hindi Film. Rutgers University Press.

Edensor, T. (2016). National Identity, Popular Culture, and Everyday Life. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Gokulsing, K. M., and Dissanayake, W. (2004). Indian Popular Cinema : A Narrative of Cultural Change. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Hayward, S. (2002). Cinema Studies : The Key Concepts. Routledge.

Hudson, D. (2012 October 9). NYUAD Hosts Shyam Benegal Retrospective. New York University Abu Dhabi. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

Kumar, R. S. (2003). Varma, (Raja) Ravi. Oxford Art Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t087983.

Neumayer, A. A., Neumayer, E., Schelberger, C., Varma, R., & Schenker, H. (2003). Popular Indian Art : Raja Ravi Varma and the Printed Gods of India. Oxford University Press, USA.

Rajadhyaksha, A., and Willemen, P. (2014). Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema. Routledge.

Sachdeva, V. (2019). Shyam Benegal’s India : Alternative Images. Taylor & Francis.

Sengupta, A. (2011). Nation, Fantasy, and Mimicry : Elements of Political Resistance in Postcolonial Indian Cinema.

Srivastava, M. (2017). Wide Angle : History of Indian Cinema. Notion Press.

Street, S. (2001). Costume and Cinema : Dress Codes in Popular Film (Vol. 9). Wallflower Press.

Thakurta, T. G., and Thakurta, T. G. (1986). Westernisation and Tradition in South Indian Painting in the Nineteenth Century : The Case of Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906). Studies in History, 2(2), 165–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/025764308600200203.

The Tribune (2006 January 29). Shyam-e-ghazal. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

Wadkar, H. (2014). You Ask, I Tell : An Autobiography. Zubaan.

Yarrow, R. (2001). Indian Theatre : Theatre of Origin, Theatre of Freedom. Psychology Press.

[1]

The 1977 Indian movie Bhumika (Role)

was directed by Shyam Benegal.

Smita Patil, Amol Palekar, Anant Nag, Naseeruddin

Shah, and Amrish Puri are the movie's stars. The

movie, which centres on a person's search for identity and self-fulfillment,

is apparently based on the Marathi-language memoirs, Sangtye

Aika, of the well-known Marathi stage and screen

actress of the 1940s, Hansa Wadkar, who led a

flamboyant and unusual life. Two National Film Awards and the Filmfare Best

Movie Award were given to the movie. It received invitations to the Carthage

Film Festival in 1978, the Chicago Film Festival, where it won the Golden

Plaque in 1978, and the Festival of Images in Algeria in 1986.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhKosh 2022. All Rights Reserved.